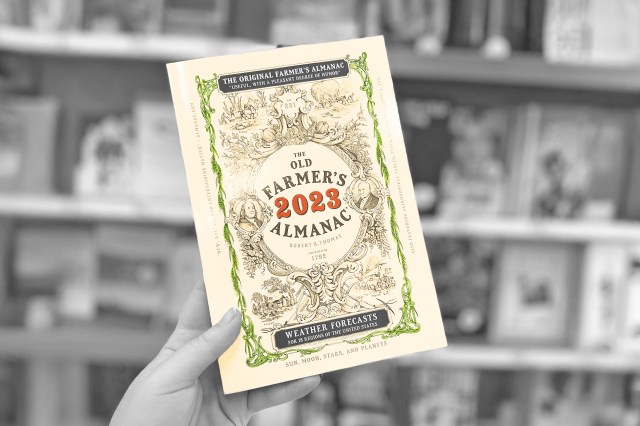

How Do Farmers’ Almanacs Predict the Weather?

Each year, millions of readers pick up a copy of the Farmers’ Almanac or The Old Farmer’s Almanac hoping for a glimpse into the future — specifically, what the next year of weather might look like. These almanacs have become staples of rural Americana, sought out not only for their forecasts but also for their folksy wisdom. But how do they actually come up with their well-known weather predictions? Let’s dive in and find out.

What Is an Almanac?

An almanac is, essentially, a calendar, usually containing information on tides, the weather, and when the sun and moon rise and set. They’ve been around in various forms since about the 12th century, when ancient Babylonian astronomers tracked and predicted planetary activity.

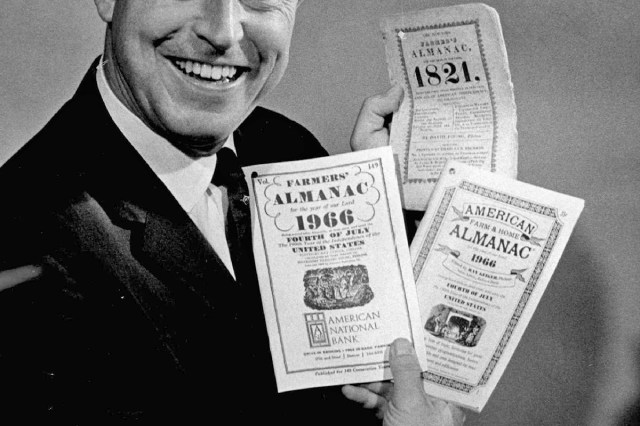

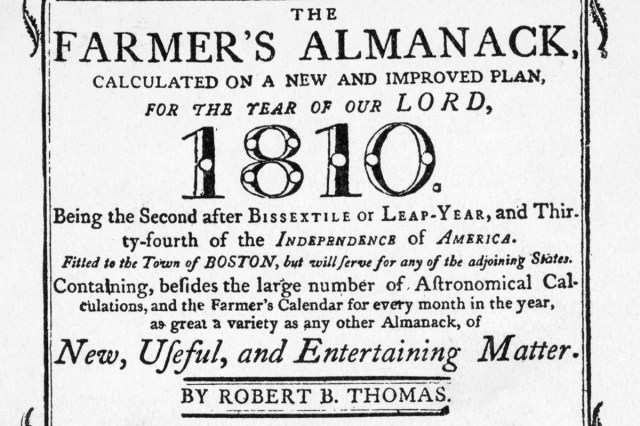

Almanacs were especially handy in agrarian societies, helping farmers plan around the weather. In 1792, Robert B. Thomas founded The Old Farmer’s Almanac. The Farmers’ Almanac, a separate publication, was first released in 1818. While both include gardening advice, home remedies, astronomical events, recipes, and more, the guides are in fact competitors — and both claim to use time-tested secret methods for forecasting the weather for broad zones across the United States and Canada.

Their Methods Are Secret

The Old Farmer’s Almanac bases its weather forecasts on a formula originally devised by Thomas himself, using a combination of solar activity, climatology (the study of weather patterns), and meteorology (the study of the atmosphere).

It also consults large, long-term weather patterns called teleconnections, the most famous of which are El Niño and La Niña, and looks for patterns in how weather has behaved under similar conditions over a 30-year average. The almanac’s formula, it says, has been refined to incorporate technology and modern science over the years, but has otherwise stayed true to Thomas’ original formulation.

The Farmers’ Almanac, meanwhile, makes weather forecasts based on a formula originally developed in 1818 by founding editor David Young; it relies mainly on changes in the sun’s activity and the moon’s movement, along with tidal patterns and high-altitude winds near the equator. It also uses comparisons to past weather patterns.

Sandi Duncan, an editor at the Farmers’ Almanac, says the forecast is prepared nearly a year ahead of time using a time-intensive manual process. While computers are used to type and organize the information, the core formula still relies heavily on human calculation and input. A mysterious forecaster known only by the pseudonym Caleb Weatherbee serves as the in-house weather prognosticator. His true identity, says the publication, is kept secret in order to protect the proprietary prediction formula.

If this all sounds rather vague, that’s because it is. Both almanacs are tight-lipped about the specifics of their weather prediction systems; The Old Farmer’s Almanac has even claimed to keep their formula locked in a black box at the company’s Dublin, New Hampshire headquarters. Both The Old Farmer’s Almanac and the Farmers’ Almanac claim their predictions are accurate about 80% of the time. But most of us know even short-range weather forecasts can be unreliable, so is that success rate really possible?

How Almanacs Compare to Modern Meteorology

Almanacs certainly share something in common with modern meteorology — a desire to understand weather patterns and make that information useful for the general public. But a widely cited University of Illinois study estimated the two main almanacs’ accuracy at only about 50%. One reason for this is the vague, generalized nature of the predictions. Rather than precise data, the almanacs tend to offer broad descriptions such as “warm and dry,” “unsettled,” or “average rainfall.” Their forecasts also cover large and geographically diverse areas (such as the Great Lakes and the Midwest) together as one zone.

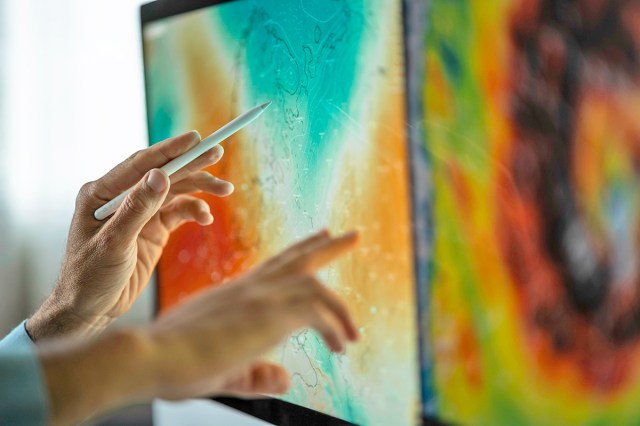

Modern meteorologists, by comparison, feed real-time data from satellites, ground radar, aircraft, and ocean buoys into complex computer models that simulate how the atmosphere will evolve and how heat, moisture, and pressure move across the planet. These models often develop much more accurate short-term predictions: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found that five-day forecasts made from its data produce accurate predictions about 90% of the time, and even seven-day forecasts were found to be accurate about 80% of the time.

Even the best forecasts, however, grow fuzzier beyond a week: According to the NOAA, 10-day forecasts are only right about half the time, as the atmosphere changes too much to accurately gather information that far ahead of time. The NOAA’s National Weather Service does produce 90-day seasonal outlooks but admits these are vague thanks to the atmosphere’s complexities.

The almanacs’ reliance on historical patterns may also mean a growing mismatch with reality: As climate change disrupts established trends and introduces unprecedented weather events that past data can’t account for, statistical models become increasingly unreliable. Today, this leaves the farmers’ almanacs somewhere between folklore and forecasting, and their value lies more in tradition than precision.

Nicole is a writer, thrift store lover, and group-chat meme spammer based in Ontario, Canada.

top picks from the Inbox Studio network

Interesting Facts is part of Inbox Studio, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.