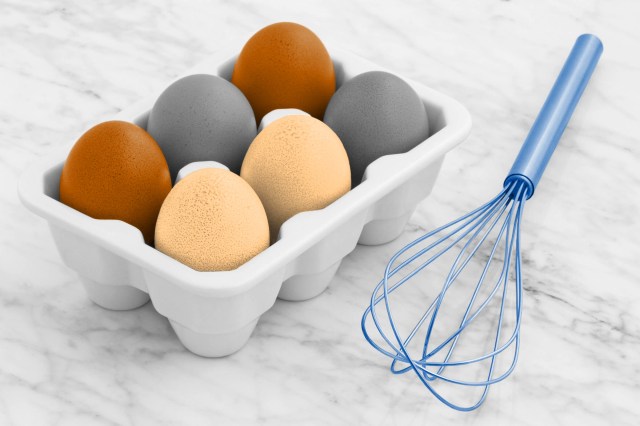

7 Egg-Cellent Facts About Eggs

Eggs are a culinary superstar, widely used in kitchens around the globe thanks to their incredible versatility and nutritional value. American egg farmers alone produce an astounding 100 billion eggs each year, as the food is one of the most common ingredients for restaurant menu items and home-cooked meals alike. In fact, more than 90% of U.S. households have eggs in their refrigerator at any given time.

Be it fried, boiled, or used in baked goods, there’s much to appreciate about the humble egg. But eggs are more than just a breakfast staple — they’re also a marvel of nature with some fascinating traits. Whether you like the sunny-side-up or over-easy, here are some egg-cellent facts about this versatile food.

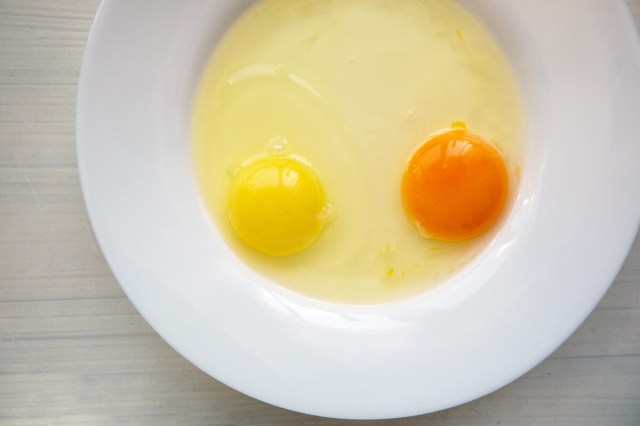

Egg Yolks Can Indicate the Hen’s Diet

The color of an egg yolk can vary from pale yellow to deep orange, a difference directly related to the hen’s diet. Hens that consume a diet rich in carotenoids — a class of pigments responsible for red, orange, and yellow hues found in plants such as corn and marigold petals — produce eggs with darker, more vibrant yolks. On the other hand, hens fed a diet low in carotenoids will lay eggs with paler yolks. While yolk color doesn’t significantly impact taste or nutritional value, many people find darker yolks more visually appealing.

The Color of the Shell Doesn’t Affect Nutrition

Eggshells come in a variety of colors, most commonly white and brown, but also blue and green in certain chicken breeds. Despite common myths, the color of an eggshell doesn’t influence its nutritional content or taste. The difference in shell color is simply a result of the breed of chicken that laid the egg. For example, white-feathered chickens with white earlobes typically lay white eggs, while brown-feathered chickens with red earlobes lay brown eggs. All eggs, regardless of shell color, provide the same essential nutrients, including protein, vitamins, and minerals.

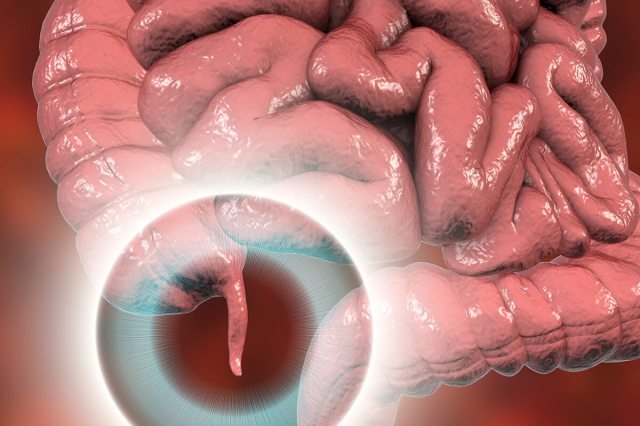

Eggs Can “Breathe” Through Their Shells

An eggshell might look solid, but it’s actually porous, containing thousands of tiny pores. These pores allow the transfer of gasses through the shell: Carbon dioxide and moisture leave the shell and are replaced by atmospheric gasses including oxygen. This exchange of gasses is crucial for the respiration of the developing embryo inside a fertilized egg. The unique porous quality of eggs is why they should be stored in their carton, as it helps maintain their quality by preventing the loss of moisture and protecting them from external odors and possible contaminants.

Older Eggs Are Easier To Peel Than Fresh Eggs When Boiled

If you’ve ever struggled to peel a hard-boiled egg, the egg’s age may be to blame. Fresh eggs have a lower pH level and a tightly bonded membrane, making the shell cling stubbornly to the cooked white. As eggs grow older, the pH level of the white increases and the membrane becomes less adhesive, making older eggs easier to peel after boiling. For the easiest peeling experience, eggs should be a week or two old (close to their expiration date) and plunged into ice water after boiling.

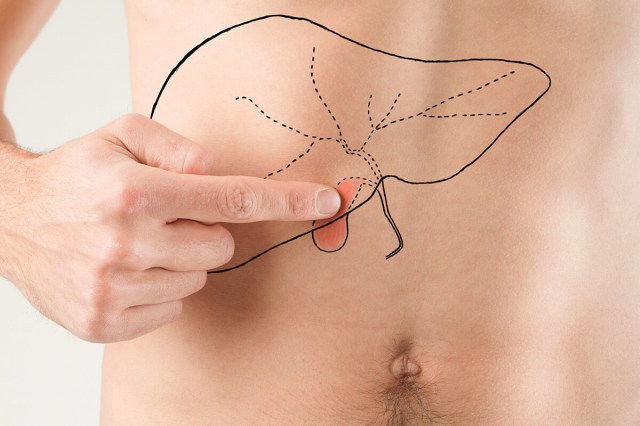

Eggs Are Jam-Packed With Nutrients

Eggs are sometimes referred to as “nature’s multivitamin” by health professionals and nutritionists — and for good reason. A single large egg contains about 70 to 80 calories, 6 grams of protein, and a range of essential vitamins and minerals, including vitamin D, vitamin B12, selenium, and choline. Choline, a vitamin-like compound that’s also produced in the liver, is particularly important for brain health and development. One large egg provides about 147 milligrams of choline, making a notable contribution toward the 400 to 550 milligrams recommended per day for adults and teens. Eggs are also one of the few natural sources of vitamin D, which supports bone health and immune function.

Eggs Age More Quickly at Room Temperature

Eggs age significantly faster when stored at room temperature compared to refrigeration. In just one day at room temperature, an egg can age as much as it would in a week in the fridge. Lower temperatures slow down the degradation of proteins and other components inside the egg, keeping it fresher for longer. As eggs age, their quality changes — the yolks and whites become thinner and more prone to breaking when separated. This explains why some recipes specifically call for fresh eggs, because the egg’s age can affect the outcome of the dish.

Eggs Purchased in the U.S. Must Go in the Fridge

In the U.S., commercially sold eggs are washed according to FDA regulations to remove contaminants, a process that also removes the natural protective coating known as the cuticle. This makes eggs more susceptible to bacteria, necessitating that they be refrigerated to maintain optimal safety and freshness. In fact, the USDA recommends eggs not be left at room temperature for more than two hours. To maximize their shelf life, eggs should be stored in their carton in the coldest part of the refrigerator, at 40 degrees Fahrenheit or below.

Some other places, including various European countries, don’t wash the eggs like they’re required to be washed in the U.S., so the cuticle remains on the shell. This allows the eggs to be safely stored at room temperature.

Kristina is a coffee-fueled writer living happily ever after with her family in the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia.

top picks from the Inbox Studio network

Interesting Facts is part of Inbox Studio, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.