It All Starts With the Limbic System

At the heart of both smiling and crying lies the brain’s emotional control center: the limbic system. This network, which includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, serves as a switchboard for our feelings.

When we experience joy, the limbic system triggers activity in the brain’s reward circuits, releasing dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins. Those chemicals signal the muscles in the face, through cranial nerves, to contract in a way that forms a smile.

Sadness activates the same brain region, but in a different way. In this case, the amygdala and hypothalamus respond by activating the autonomic nervous system, which influences tear production. The lacrimal glands just above our eyes receive the signal and respond by producing emotional tears distinct from reflex tears (the kind that protect the eyes from dust or onions).

In both scenarios, the limbic system is the unseen conductor, arranging expressions that not only reflect how we feel but also how we communicate it to the outside world.

Smiling Developed as a Social Tool

Smiling primarily involves the facial muscles, especially the zygomaticus major, which lifts the corners of the mouth. A genuine, involuntary smile — known as a Duchenne smile — also engages the orbicularis oculi muscles around the eyes, creating the crinkling effect that distinguishes true happiness from a polite grin. These smiles are triggered by the brain’s release of “feel-good” neurotransmitters including dopamine and serotonin, reinforcing pleasurable experiences.

Interestingly, the act of smiling can actually create a positive feedback loop in the brain. Psychologists have found when we smile, even if by force, it can trick the brain into releasing more dopamine and reinforce the sense of happiness. This is known as the facial feedback hypothesis, the idea that our expressions don’t just reflect emotions but can also help generate them.

From an evolutionary perspective, smiles likely developed as a social tool. A smile can signal friendliness, cooperation, or safety, helping people build social bonds. In early human societies, this would have strengthened trust and encouraged group cohesion — an essential advantage for survival.

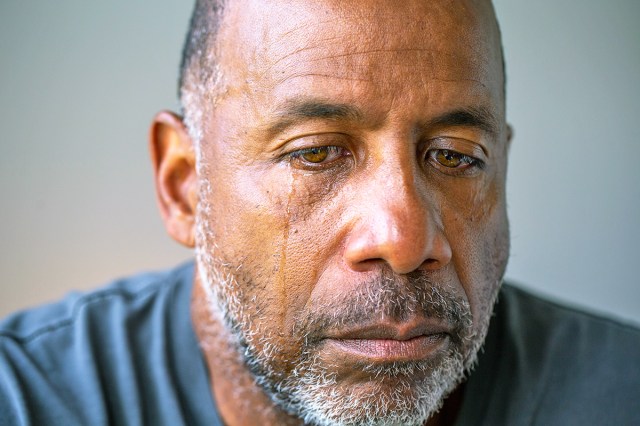

How Crying Helps Us

Crying when we’re sad may feel like a loss of control, but it’s a deeply human response. Emotional tears differ from basal tears (also called continuous tears), which keep our eyes lubricated or the reflex tears that flush out irritants. Emotional tears contain higher levels of stress hormones such as cortisol, as well as endorphins that help stabilize your mood after crying.

This process begins in the hypothalamus, which detects emotional stress and sends signals to the parasympathetic nervous system. The lacrimal glands then produce tears, while the orbicularis oculi muscles contract around the eyes. Crying slows breathing and lowers heart rate, allowing the body to shift into a calmer state — a built-in form of self-soothing.

Like smiling, crying also has a strong social function. Tears are a nonverbal signal to others that we’re in need of comfort, support, or empathy, and studies show people are more likely to approach and console someone who is visibly crying. This social response likely explains why humans evolved the capacity for emotional tears — something no other animal seems to have.

More Interesting Reads

Humans Evolved To Smile and Cry

Beyond individual biology, emotional expressions have deep evolutionary roots due to the social purposes they serve. Our friendly smiles and vulnerable tears promote group cohesion and mutual support to this day, but they were also vital for early human survival.

Research shows that emotional expressions are instinctive rather than learned. Babies smile and cry long before they can speak, suggesting these behaviors are hardwired. And cross-cultural studies confirm people around the world recognize basic emotions through facial expressions — even when factoring in cultural differences in how emotions are expressed — highlighting the universal biology at play here.

Throughout human history, evolution likely favored individuals who could effectively convey emotions to their community, ensuring understanding and cooperation within their groups.

Emotional Expressions Are Crucial

In modern life, our emotional expressions continue to serve important purposes. Smiling when we’re happy can strengthen our personal relationships, improve our mood, and even influence how others perceive us, while crying when we’re sad can provide relief and foster empathy. Brain imaging studies show observing a smile or tears can activate similar regions in the observer’s brain, demonstrating how expressions promote emotional connection.

In these ways, our face becomes more than just a reflection of your inner state — it also sends messages to others around us, reinforced by millions of years of evolution.