The “War of the Currents”

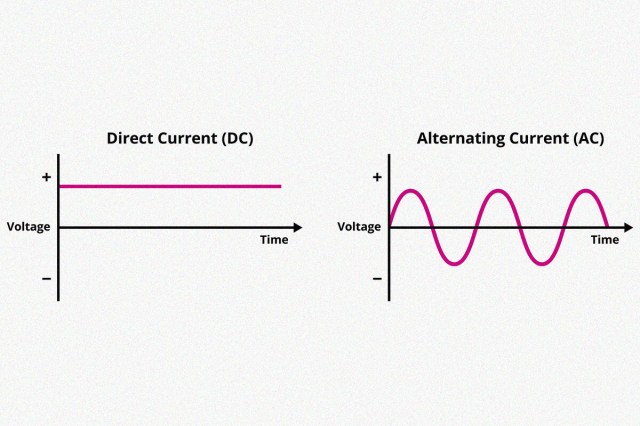

At 3 p.m. on September 4, 1882, an engineer working on Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Station flipped a switch. Suddenly, six coal-powered dynamos instantly illuminated some 400 lamps belonging to 82 customers living only a quarter mile from the world’s first power station, in New York City. Edison’s groundbreaking system operated on 110 volts (the difference of electric potential between two points) because it worked well with his newly introduced incandescent light bulbs. It also ran on direct current (DC), meaning power flowed continuously in one direction.

However, the pioneering work of Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse soon showed that alternating current (AC), which is when current frequently reverses direction, could actually travel longer distances more efficiently. The ensuing “war of the currents” ultimately ended with AC emerging victorious.

Soon, AC power began streaming into American homes and businesses, running at Edison’s previously established 110 volts but at Westinghouse’s 60 hertz — the frequency that determines how many times a current changes direction per second. Although the U.S. tweaked the standard voltage up to 120 volts in the 1960s, this arrangement remains largely unchanged — to this day, U.S. outlets continue to support 120 volts.

But as the rest of the world slowly electrified, not everyone agreed with the standards set by the U.S.

Less Current, More Voltage

While 110 volts may have been all well and good for Edison’s lightbulbs back in the late 1800s, European countries and companies realized this was not the most efficient (nor the cheapest) way to actually transmit electricity. To understand Europe’s beef with Edison, let’s take a quick detour into the simple math behind electrical transmission.

You can easily calculate electrical power by multiplying voltage by current (P = V * I). Current (I) is the rate at which electrons flow through a conductor, while voltage is the force applied to move that current. If current is high, you need thicker cables to safely transmit electricity. However, if you increase the voltage in this simple equation, you can actually lower the current and still arrive at the same power level.

This has the immensely beneficial side effect of allowing companies to use thinner copper wires, a material that can be pretty costly even in the best of times (and especially in war torn Europe in the early 20th century). Apart from saving some serious cash, countries also wanted to design their own plugs because the U.S.’s was notoriously unsafe and uninsulated. Additionally European countries — mainly Germany — wanted to use 50 hertz instead of 60 because it aligned better with the metric system.

The idea of countries developing their own electric standards may seem odd in our interconnected modern world, but in the 20th century, electric appliances were so few and travel distances so long and laborious, no one foresaw the need for international standardization. But by 1934, people at the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) had begun to think some form of standardization for electrical fittings might be a good idea. Unfortunately, this governing body only met twice before the outbreak of World War II, and by the time it reconvened in 1950, many countries were already entrenched in their own electrification schemes.

There Is a “Universal” Plug Type (But Only Two Countries Use It)

That doesn’t mean there haven’t been efforts to unify the world around one outlet to rule them all. Today, there are around 15 types of plugs, each denoted with a letter. The U.S. uses Type A and Type B plugs (two-pronged and three-pronged, respectively) while most of Europe uses Type C, E, and F plugs. Meanwhile, Italy uses type L, Switzerland uses Type J, Denmark uses Type K, and England uses Type G. Type G includes a fuse within the plug itself, making them the safest (and most cumbersome) plugs in the world.

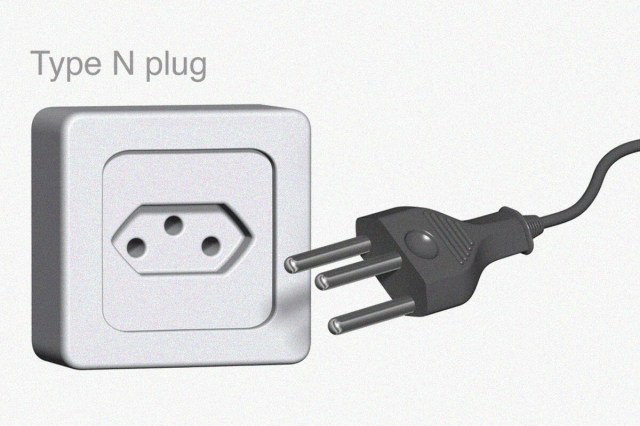

Once you venture outside North America and Europe, things get even more complicated. In an attempt to organize this chaos, the IEC introduced the International Standard IEC 906-1 in 1986, known as the Type N plug, a universal plug that could work across borders. Yet nearly 40 years after its introduction, only two countries — Brazil and South Africa — have adopted the standard. The main problem is that while a universal plug and outlet system would make life easier for travelers, few countries have the will to invest billions to switch from one plug type to another. So for now, make sure you have the necessary gear to power your devices before commencing your globe-trotting.