How Are the Eight Blood Types Different?

Our blood is made up of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in a liquid called plasma. Our blood type, also known as our blood group, is determined by special proteins called antigens that sit on the surface of red blood cells. Landsteiner discovered that the nature of those antigens differs between people and that four main blood groups exist, which he defined as the ABO system.

If you have type A blood, your red blood cells carry A antigens. Type B blood has B antigens and type AB has both A and B antigens. Type O blood, meanwhile, has neither A nor B antigens. But the classification doesn’t end there.

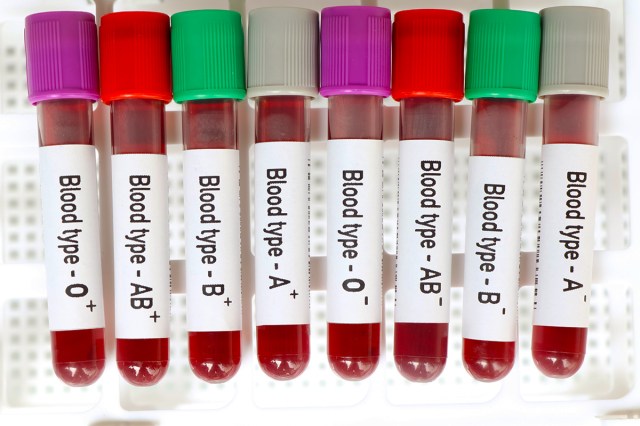

In 1940, Landsteiner and his colleague A.S. Weiner discovered a second significant blood group factor based on the presence or absence of the Rh antigen, often called the Rh factor, on the cell membranes of red blood cells. Your blood type is classified as positive (+) if the Rh factor is present in your blood and negative (-) if it’s absent. Taken together, this creates the eight common blood types: A positive, A negative, B positive, B negative, AB positive, AB negative, O positive, and O negative.

What Determines Your Blood Type?

Everyone inherits their blood type from their parents, just like eye color, height, handedness, and freckles. Blood types follow simple inheritance rules: Each parent gives you one blood type gene, and the combination determines your blood type. The genes for A and B blood types are codominant — in other words, they dominate equally — while the gene for blood type O is recessive.

So if you inherit an A gene from one parent and an O gene from the other, you’ll have Type A blood because A is stronger. You need two O genes (one from each parent) to have Type O blood. If you receive both A and B genes, you’ll have Type AB blood since both are equally strong.

Globally, the most common blood type is O positive, with more than a third of the population sharing it, followed by A positive. The rarest of the standard blood types are AB positive (2% of the population) and AB negative (1%), which can make finding a match difficult in some cases.

Rh status is also inherited from our parents, albeit separately from our blood type. If you inherit the dominant Rh antigen from one or both of your parents, then you’re Rh-positive (about 85% of the population). If you don’t inherit the Rh antigen from either parent, then you’re Rh-negative — and therefore your blood type will be negative.

The Universal Donor

Blood type compatibility is crucial for enabling safe medical procedures. Before the discovery of blood types, blood transfusions that weren’t a match could result in clumping, or agglutination, of red blood cells. Those clumps could block small blood vessels throughout the body, depriving tissues of oxygen and nutrients, causing numerous problems and even fatality.

Receiving blood from the wrong ABO group can be life-threatening because antigens present on red blood cells can trigger an immune response if they’re not compatible. For example, if someone with group B blood is given group A blood, their anti-A antibodies will attack the group A cells.

The exception to this is type O, as those red blood cells don’t have any A or B antigens. Type O negative, specifically, can safely be given to any other blood type because it’s compatible with all groups. This is why people with O negative blood are considered “universal donors” (in the U.S., only about 7% of the population are O negative) and also why, during medical emergencies when the blood type is not immediately known, doctors will often use O negative blood.

Conversely, people with O positive blood can only receive transfusions from O positive or O negative blood types, because their anti-A and anti-B antibodies would attack any donor blood with A or B antigens. The only blood type that can receive blood from any other type is AB positive, which is therefore known as the universal recipient.