New York City’s Times Square Wasn’t Always Called That

For the most-visited tourist site in the U.S., New York City’s Times Square had humble beginnings. Once an area surrounded by countryside and used for farming by American Revolution-era statesman John Morin Scott, the area now known as Times Square fell into the hands of real estate mogul John Jacob Astor in the 1800s. By the second half of the 19th century, it had become the center of the city’s horse carriage manufacturing industry and home to William H. Vanderbilt’s American Horse Exchange. City authorities named it Long Acre Square, a reference to London’s historic carriage and coach-making district. This name remained until 1904, when The New York Times moved its headquarters to a lavish new skyscraper called One Times Square. Just eight years later, the newspaper relocated again to a nearby building, but the name Times Square stuck.

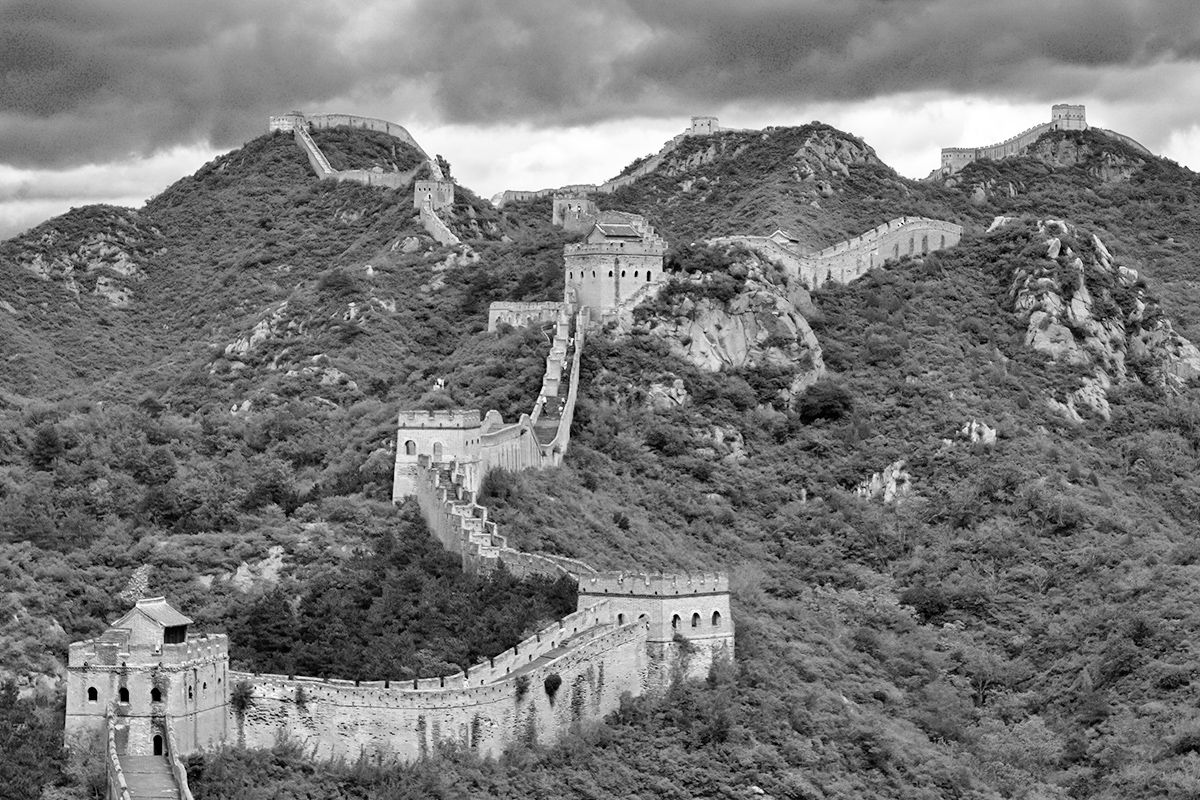

The Great Wall of China Isn’t a Continuous Structure

Built from the third century BCE to the 17th century CE in order to keep out northern invaders, the Great Wall of China is considered the world’s longest wall, extending a total 13,170 miles. Although our mental image of the Great Wall is probably one of a continuous structure winding its way across China, the reality is different. The Great Wall is actually composed of various stretches of wall and watchtowers — often with gaps between. There are even areas where the wall is non-existent. The original builders also made use of natural barriers to keep invaders out. As much as a quarter of the wall’s length relied on features like rivers and mountainous ridges to keep the marauding hordes back. Today, much of the wall is in ruins, but sections that date from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) can still be seen.

Las Vegas Is the Brightest City on Earth

About 80% of the world’s population lives in a place lit up by artificial light at night. And according to NASA, nowhere do those lights shine brighter than in Las Vegas. A city that loves its neon signs and bright marquees, Las Vegas offers an around-the-clock dose of sensory overload — even New York City, “the city that never sleeps,” and Paris, “the city of lights” can’t match the over-the-top light show of Las Vegas when viewed from outer space. And in a city with so much artificial light, one manages to stand out: the Sky Beam atop the Luxor Hotel pyramid. It’s powered by 39 ultra-bright xenon lamps (each 7,000 watts) and curved mirrors that collect their light and focus them into the world’s strongest beam of light. Not only can it be seen from space, but the Sky Beam provides enough illumination to read a book from 10 miles out in space.

Gustave Eiffel Helped Designed the Statue of Liberty

Even prior to the building of his namesake tower in Paris, Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel was already one of France’s leading structural engineers in the 19th century. Thus, he was a natural choice for New York Harbor’s Statue of Liberty, especially after the statue’s original designer died unexpectedly. Thanks to Eiffel, the statue’s interior boasts a more contemporary design. Eiffel came up with the idea of a central spine in the statue, which functions as a connector for the various asymmetrical metal girders that give the statue its shape. This innovative technique not only provides the framework for the statue but also creates a kind of suspension system that allows the monument to withstand winds and other harsh weather conditions.

The Great Barrier Reef Is So Large You Can See It From Space

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef ecosystem on the planet, covering an area of approximately 135,000 square miles. It’s not just the immense scale of the reef that makes it visible to astronauts in space, though. The contrast between the dark blue of the deeper parts of the ocean and the light turquoise of the lagoons on the other side of the reef makes it relatively straightforward to identify with the naked eye. But the pictures taken from space are valued for more than their aesthetic appeal. The MERIS sensor used on the Envisat satellite mission was a useful tool in mapping the extent of coral bleaching, the term for when stressed coral has rid itself of algae.

More Interesting Reads

The Grand Canyon Isn’t the Deepest Canyon in the U.S.

Given its name, it’s a common misconception that the Grand Canyon is the deepest canyon in the United States. The Grand Canyon is very deep — 4,000 feet deep, in fact, with the deepest point reaching 6,000 feet. This gives it an average depth of about a mile. But Hells Canyon, running along the border of Oregon and Idaho, exceeds the depth of the Grand Canyon by plunging nearly 8,000 feet in some places. While not the country’s deepest canyon, the Arizona landmark has other impressive stats: It extends for 277 miles and measures 18 miles wide. Totaling 1,904 square miles, this canyon is roughly the size of Rhode Island. And the national park there is visited by around 6 million people each year.

We Know of the “Lost” City of Petra, Jordan, Thanks to a Swiss Explorer

Once a thriving cultural and economic hub, Petra (believed to have been established around 312 BCE) was later abandoned and left to ruin. For centuries, all except the local Bedouin people forgot Petra — its tombs and temples carved directly into the sandstone cliffs were abandoned and buildings fell into ruin, hidden by the surrounding canyons. But in 1812, a Swiss explorer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt set off on an expedition in search of the source of the River Niger. On his way to Cairo, he heard rumors from locals of secret ruins of a grand city in the desert, so he hired guides and disguised himself as an Arab to gain access to what was considered a sacred place, forbidden to Westerners. They brought him to Petra. However, wary of pushing his luck too far, he didn’t stop to excavate. Five years later, Burckhardt died of dysentery in the Egyptian capital, but his “discovery” paved the way for future exploration of the site.

The Golden Gate Bridge’s Color Was Supposed To Be Temporary

San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge features a distinctive reddish-orange paint color — but it came about by accident. Architect Irving Morrow noticed that some of the steel that arrived for construction of the bridge was coated in a dark red primer, which inspired him to write a 29-page report in 1935 advocating for a similar color to be used in the bridge’s final design. Although most bridges at the time were painted gray, silver, or black, he suggested using paint in a shade like orange vermillion or burnt sienna, as these luminous tones would emphasize the grand scale of the bridge and provide a contrast to the grey and blue color of the water beneath. Not everyone agreed, but in the end, Morrow won over his critics. The bridge was painted a shade unimaginatively called “International Orange,” and it’s been the same ever since.

Machu Picchu’s Buildings Were Designed To Be Earthquake-Proof

The Inca people certainly knew how to build to accommodate their environment. That’s evident not only in Machu Picchu’s epic surroundings, but also in the foundation of the Lost City itself. Peru is located in a seismic zone, and the Incas were familiar with potential earthquakes. To protect against them, they made the buildings of the citadel seismic-resistant by using precisely fit stones held together by gravity alone. Nothing so thin as a credit card could be inserted in the cracks, allowing the mortar-free stones to “dance” during an earthquake, only to resettle back into place once it ends. Additionally, the Incas cornered structures with L-shaped blocks, built terrace buttresses into steep mountain slopes, rounded the corners in some buildings, and tilted the trapezoidal doors and windows inward. All of these small but ingenious details ensured that their structures were earthquake-ready.

There’s a Secret Suite Inside Disney World’s Cinderella Castle

Cinderella’s castle at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, holds a few secrets. For starters, the bricks used to build the tops of the tall towers are smaller than the bricks used for the lower part of the structure — an engineering trick used by the designers in many buildings here to make them appear even taller than they truly are. Perhaps even more surprising, there’s a hidden suite inside this castle that was originally designed to be an office for Walt Disney himself, but he died before the castle was completed. Cinderella’s castle isn’t the only one hiding a surprise: Sleeping Beauty’s resting place (at Disneyland in California) boasts an actual working drawbridge. Reportedly, it has been used just twice, once for the opening ceremony in 1955 and again in the 1980s when Fantasyland opened.

The Taj Mahal’s Four Minarets Look Perpendicular — But They’re Not

In the 1600s, Mughal emperor Shah Jahan built India’s Taj Mahal to honor the memory of his third wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Four 130-foot-tall minarets surround the Taj Mahal’s central tomb, where Shah Jahan and his wife are both buried, and showcase the emperor’s passion for symmetrical design. At first glance, they seem to stand perfectly perpendicular to the ground; however, on closer inspection you’ll notice they are tilted slightly outwards. This wasn’t a design fault, but rather a way to protect the tomb in the event of a natural disaster — should the minarets fall, then the material would land away from the building. The four towers were built to be used by a muezzin, the person who calls daily prayers, and each features two balconies and an elevated dome-shaped pavilion, called a chattri.

Beijing’s Forbidden City Is the World’s Largest Imperial Palace

Occupying some 7.7 million square feet, the Forbidden City is the largest imperial palace on the planet. The most-visited UNESCO World Heritage Site in the world, it features 980 individual buildings, which are home to almost 9,000 rooms. There are two distinct areas: The Inner Court served as the emperor’s residence, while the Outer Court was for ceremonial events. A 32-feet-high defensive wall protects the entire complex, around which is a 171-foot-wide moat. What’s inside is even more impressive: The palace is home to a reputed 1.9 million artifacts — everything from calligraphy, ceramics, and paintings to gold and silverware, literary works, and religious icons.

Some of the Stones at Stonehenge Came From Nearly 200 Miles Away

Located in Wiltshire, England, Stonehenge — roughly 5,000 years old — is one of the world’s most enigmatic monuments. It consists of roughly 100 bluestones and sarsens positioned upright and arranged in a circle. While the larger sarsens (a type of sandstone boulder) were hewn from the Marlborough Downs, which is relatively close to the site, the smaller bluestones have been traced to the Preseli Hills in southwest Wales, over 180 miles away. It’s hard to believe that its Neolithic builders — who lacked sophisticated tools or engineering — floated and dragged many of these giant lumps of rock over such a great distance, which only adds to the mystery of the original purpose of the stone circle.

Cambodia’s Angkor Wat Temple Is the World’s Largest Religious Structure

Sprawling across more than 400 acres in northern Cambodia, the Angkor Wat temple complex is the world’s largest religious structure. Erected by the Khmer Empire in the 12th century, this awe-inspiring monument began as a Hindu temple and was later converted into a Buddhist place of worship. The temple design is an architectural portrayal of Mount Meru, which is the center of the Hindu universe. The five towers represent the five peaks of the mountain, and the surrounding moat and defensive wall symbolize the oceans and mountain ranges. How colossal is Angkor Wat? It’s so large that many of its features are visible from space — just like the Sky Beam in Las Vegas and the Great Barrier Reef.

The Great Pyramid of Giza Was Once Fully Covered in White Limestone

The only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still standing, the Egyptian Pyramid of Giza was constructed around 2550 BCE. At 454 feet tall, it was the world’s tallest building at the time — a title it held until the 14th century. In contrast to the weathered sand-colored blocks you see today, the pyramids were once completely covered in polished limestone. This higher-quality stone was quarried at a place called Tura, which was about nine miles south of Giza. Its smooth, white surface would have gleamed in the sunshine, creating a dazzling effect. Today, most of the casing is gone except for a cap on the peak of the Pyramid of Khafre (Chephren), which has dulled over time.