Pharaohs Were the Political and Spiritual Leaders of Egypt

The most important duty of pharaohs was preserving the cosmic order, called maat, which they did by enacting laws, defending the kingdom against its enemies, managing all the land (which belonged to the pharaoh), and even collecting taxes. Both pharaohs and ordinary Egyptians were expected to live according to the moral principles of maat, but the pharaoh was additionally tasked with maintaining peace between the gods and the people and keeping chaos at bay. As the intermediaries between the gods and humans, pharaohs led religious festivals, built temples honoring deities, and carried out divine imperatives.

Pharaohs Identified With the Gods Horus and Osiris

The story of Osiris, the Egyptian god of the underworld, fertility, and rebirth, forms the foundation of ancient Egyptian kingship. In the myth, Osiris was the first king of Egypt and ruled with Isis, his queen. Benevolent Osiris taught the people to prosper, but he had an evil brother, Seth — embodying the opposite of maat — who killed and dismembered Osiris so he could take the throne. Isis was able to put his parts mostly back together, and Osiris became the god of the underworld, while his son Horus got revenge on Seth and became pharaoh. (According to one story, Horus killed Seth with a spear after the latter had transformed himself into a hippo.)

The legend served as a model for the actual pharaohs, who were identified with Horus during their lifetime and then with Osiris after death, and whose rule was characterized as a continuation of the existential battles between Horus and Seth.

Pharaohs Were Believed to Control the Nile

The Nile was central to ancient Egypt. It provided food and water, fertile lands for agriculture, and a blue highway for travel and shipping — and without the river, it’s unlikely that the desert dynasties would have existed. Its annual flooding, which replenished the lands for crops and livestock, was personified in a god named Hapi who had green or blue skin (representing water) and a pot belly (signifying fertility and abundance). As the religious leaders of the Egyptian people, pharaohs conversed with Hapi to ensure the flooding occurred on time. But if the floods were too strong or destroyed homes and farms, the pharaohs were blamed for not keeping the cosmic order up to snuff, which led to political instability.

More Interesting Reads

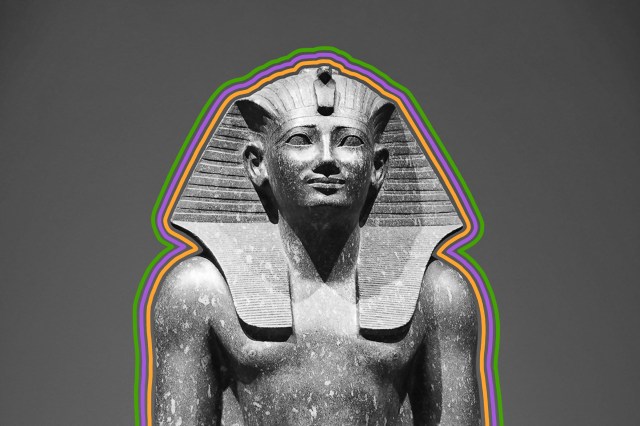

Women Were Influential Pharaohs

Generally, pharaohs were men whose power passed to their sons, but some female pharaohs ruled Egypt in their own right. Hatshepsut, the queen of Pharaoh Thutmose II, rose to power after his death and reigned as pharaoh from 1472 to 1458 BCE. She led military campaigns and built massive temples, and at the height of her influence was depicted in statuary as a muscular, bare-chested monarch wearing a false beard like male pharaohs sported.

Scholars debate whether Nefertiti ruled explicitly as pharaoh in the 1330s BCE, but it’s certain that she was the queen of Pharaoh Akhenaten and likely the stepmother of another pharaoh, Tutankhamun. She is shown in artifacts in ways normally reserved for pharaohs — and then there’s that undeniably regal bust of Nefertiti, unearthed in 1912, which fueled speculation about her true role. She may have assumed power after Akhenaten’s death while Tut was still young, but the debate continues.

Cleopatra VII, who reigned from 51 to 30 BCE, is probably the most famous female pharaoh of all, thanks to the 1963 Hollywood epic starring Elizabeth Taylor. Though that movie focuses on her love affairs, Cleopatra was much more than a seductress; she was a popular ruler who made reforms of the monetary system, helped increase Egypt’s wealth through trade with Eastern nations, and allied with Roman factions in an attempt to keep Egypt independent.

Pharaohs Were Buried in Extravagant Tombs

Pharaohs were laid to rest in huge, richly ornamented tombs to ease their transition to the realm of Osiris. In the Fourth Dynasty (2575 to 2465 BCE) of the Old Kingdom, the three Pyramids of Giza were commissioned for the pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. Each pyramid there is essentially solid stone with a small burial chamber at ground level or underneath; unfortunately, thieves plundered the tombs centuries ago, and the items buried with the pharaohs to aid them in the afterlife are lost.

A thousand years later, in the New Kingdom, pharaohs were buried in smaller, multi-chambered tombs in the Valley of the Kings, about 330 miles south of Giza. About 64 tombs are scattered across the valley, including those of Thutmose I and his daughter Hatshepsut, Ramses II (aka the Great), and Tutankhamun. All but Tut’s were looted long ago, which is what made the 1922 discovery of his nearly intact tomb, with its hoard of gold objects and furniture, a world-shaking event.

Pharaohs Issued Curses — But Not the One You May Be Thinking Of

According to legend, King Tut supposedly cursed the British archaeologists who disturbed his eternal rest. Roughly nine people involved in the tomb’s excavation died within a few years of their discovery, which the media whipped into stories about a “curse of the pharaohs.” No actual curses were found inside Tut’s tomb, however, and the Egyptologist David P. Silverman argues that pharaohs rarely issued them, since they already enjoyed protections from the gods. The few known royal curses serve as warnings against enemies of Egypt or members of court, and they could be pretty graphic.

“As for [anyone] who will come after me and who will find the foundation of the funerary tomb in destruction,” a curse in a temple devoted to Pharaoh Amenhotep warns, “His uraeus [a serpent-shaped headdress ornament] will vomit flame upon the top of their heads, demolishing their flesh and devouring their bones.”