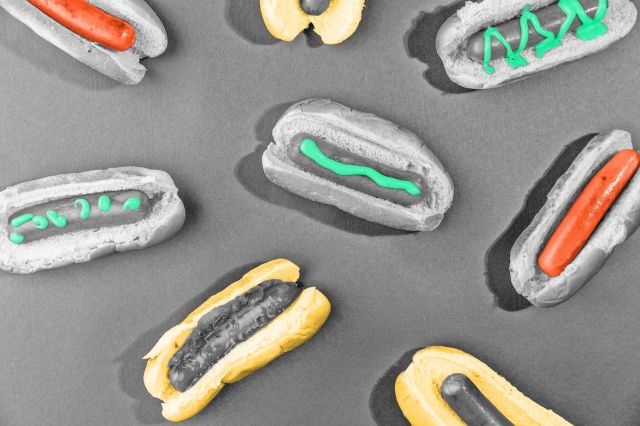

Hot Dogs

Despite originating in Germany, hot dogs are an essential American food — an estimated 7 billion hot dogs are served up each summer in the U.S. alone. And with that many sausages on the grill, the name for a food that doesn’t involve any actual dogs has become completely mainstream. But where did it come from? Some food historians believe that early songs and jokes gave the wieners their name, suggesting that sausage meat came from dogs. But a more likely story is that German butchers named early American frankfurters “dachshund sausages” after the long and skinny dogs they resembled, which was eventually shortened to “hot dogs.”

Sweetbreads

Beware the common confusion about sweetbreads: They’re neither sugary nor baked. That’s because sweetbreads aren’t at all a pastry, but instead a type of offal (organ meats). These small cutlets are actually the thymus and pancreas glands from calves or lambs. While sweetbreads may seem off-putting to some diners, they’re known by many chefs to be exceptionally tender with a mild flavor — which could explain their misleading name. The first recorded mention of the British dish dates to the 1500s, a time when “bread” (also written “brede”) was the word for roasted or grilled meats. In conjunction with being more delicate and flavorful than tougher cuts, the name “sweetbread” likely took hold.

Head Cheese

There’s no dairy involved in making head cheese. In fact, the dish more closely resembles a meatloaf than a slice or wedge of spreadable cheese. That’s because head cheese is actually an aspic — a savory gelatin packed with scraps of meat and molded into a sliceable block. As for the name, head cheese gets its label in part from the remnants of meat collected from butchered hog heads. And while not a cheese, it’s likely the dish is named such because early recipes called for pressing the boiled meats together in a cheese mold. Head cheese is popular throughout the world, especially in Europe, where it’s known by less-confusing names. In the U.K. butchers call the dish “brawn,” and meat-eaters in Germany refer to it as “souse.”

More Interesting Reads

Pumpernickel Bread

Most bread names are self-explanatory: cinnamon-raisin, sandwich wheat, potato bread. So what exactly is a “pumpernickel”? Originating in Germany, this dark and hefty bread combines rye flour, molasses, and sourdough starter for a dough that bakes at low heat for a whole day. Many American pumpernickel bakers speed up the process by using yeast and wheat flour, which makes for a lighter loaf that reduces (or altogether removes) pumpernickel’s namesake side effect: flatulence. German bakers of old acknowledged the bread’s gas-inducing ability with an unsavory nickname: pumpern meaning “to break wind,” and nickel for “goblin or devil.” Put together, the translation reads as “devil’s fart” — a reference to how difficult pumpernickel could be on the digestive tract.

Jerusalem Artichokes

If there’s any vegetable that suffers from bad branding, it may just be the Jerusalem artichoke — a bumpy root crop that’s not actually an artichoke and doesn’t have any link to Israel. Unlike their real counterparts, Jerusalem artichokes are actually the edible tuber roots of a sunflower species, similar in appearance to ginger root (real artichokes produce purple, thistle-like flowers that turn into above-ground edible bulbs). Jerusalem artichokes were first called “sunroots” by Indigenous Americans, who shared the tubers with French explorers in the early 1600s. Upon arriving back in France, the vegetables were called topinambours. Italian cooks renamed them girasole, aka “sunflower,” in reference to their above-ground buds. As sunroots spread throughout Europe, the girasole morphed into “Jerusalem” thanks to mispronunciation, with the addition of “artichoke” in reference to the vegetable’s flavor.

Dutch Baby Pancakes

Few foods are universal, but pancakes may be the exception. While they may be made with culture or region-specific ingredients, nearly every country has some variation of the pancake. Queue the Dutch baby, a baked treat with a name that misidentifies both its origin and size. Also known as a German pancake or pfannkuchen, Dutch babies are a blend of popovers and crepes baked in a large skillet or cast-iron pan, topped with fruit, syrup, or powdered sugar. So how did these dinner-plate-sized pancakes get their most popular moniker? Culinary legend attributes the misnomer to the daughter of a Seattle restaurant owner, who mistakenly subbed “Dutch” for “Deutsch” (meaning German). The eatery downsized its versions into miniature servings and deemed the pancakes “Dutch babies.”

Grasshopper Pie

Insects are protein-packed main courses in many countries, but the idea of chomping down on bugs isn’t appealing to all stomachs. Luckily, this bug-branded dessert is entirely free of its namesake insect. Grasshopper pie features a cookie crust and fluffy filling made from whipped cream, mint and chocolate liqueurs, and green food coloring. Fittingly, grasshopper pie often makes its appearance at springtime celebrations just as the leaping bugs are emerging from their winter slumber, but that’s not where the name comes from. While hitting peak popularity during the 1950s and ‘60s, grasshopper pie is actually a dessert version of the grasshopper cocktail, which first debuted some four decades prior. Philibert Guichet, a New Orleans restaurateur, invented the drink as part of a cocktail competition in 1919, naming his creation for its bright green hue.