Ukiyo-e

Translated from Japanese, ukiyo-e literally means “pictures of the floating world.” A nod to the ephemeral nature of normal life, the paintings often depicted cultural touchstones like kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers. The movement’s signature style, which emerged around the 1670s, revolved around woodblock prints that featured thick flat lines and bold colors, like those seen on Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Decades later, ukiyo-e’s daring use of color and shapes would inspire the French impressionists.

Romanticism

After the Enlightenment brought a flourishing of rational thought and scientific advancements in the 18th century, artists began pondering how progress had diminished humanity’s connection to the transcendent. There had to be more to existence, right? The resulting Romantic era, which began in the late 1700s and continued into the next century, saw philosophers celebrate the “genius” of individual artists, treating painters and musicians as God-like conduits with special powers that could connect humans with the sublime — the awe of the natural world. Paintings often united one’s strong emotions with nature, like John Constable’s “Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground,” and others portrayed nature as violent and terrifying, like in Théodore Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa.” Other artists from the romanticism period include Francisco Goya, J.M.W. Turner, and Caspar David Friedrich.

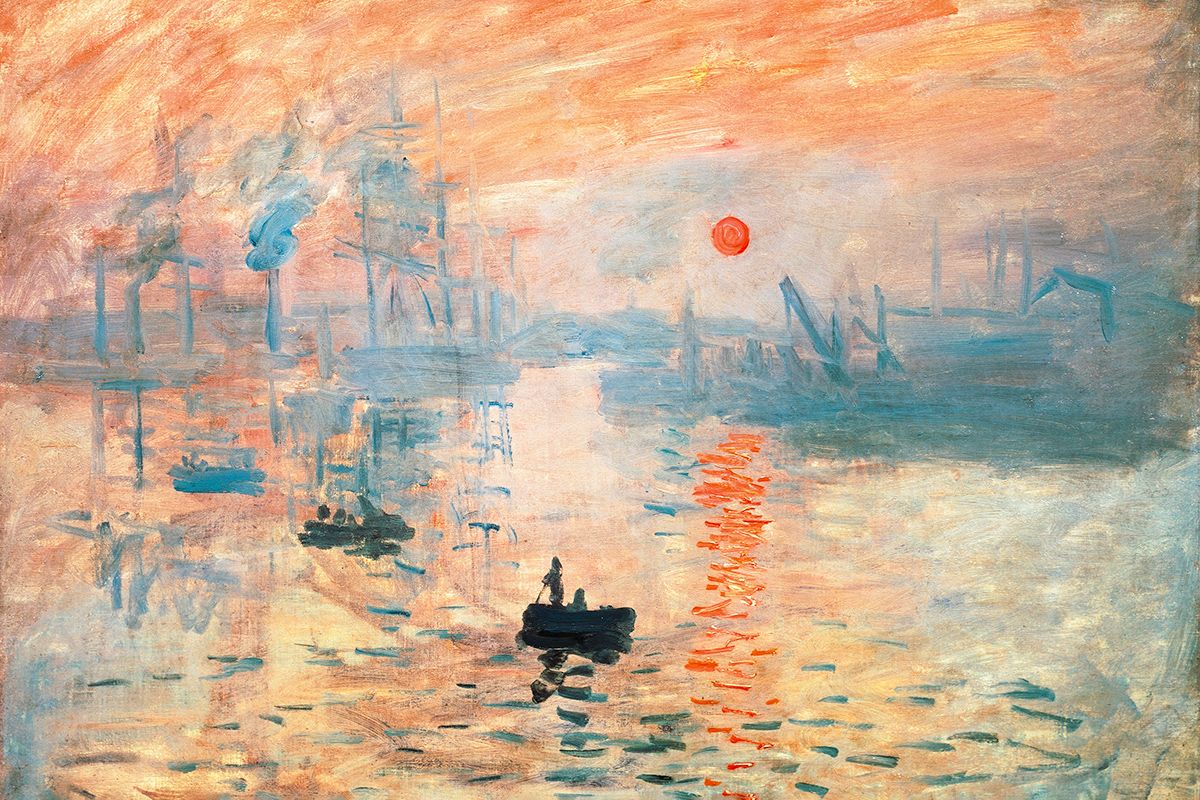

Impressionism

In 1872, Claude Monet finished his oil-on-canvas “Impression, Sunrise,” depicting the murky coastal seascape of the port of Le Havre, France. Soon, the word “impressionism” was being thrown around to describe the surge of ethereal, blurry paintings by Monet and other French painters such as Camille Pissaro, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet. The movement was a revolt against the increasingly stuffy stylings of the French academic establishment, which had spent decades placing a premium on clean lines and photographic realism. Notable works from this movement include “L’Absinthe” by Degas, “Luncheon of the Boating Party” by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” by Manet.

More Interesting Reads

Fauvism

A step between impressionism and surrealism, fauvism briefly swept France during the early 20th century. Fauvists exaggerated the colors of their subjects. A warm sunset might be painted a deep maroon, while a dusky street scene could come alive in ultramarine. The colors were bold, bright, and brash, like in “Blackfriars Bridge London” by André Derain. What the paintings lacked in realism, they made up for in their vibrant expression — fauvist works popped with personality. Unsurprisingly, conservative members of the artistic establishment were not fans: They denounced the paintings as the work of “Les Fauves” — that is, wild beasts.

Cubism

In 1908, the critic Louis Vauxcelles described the work of Parisian painter Georges Braque as “geometric schemas and cubes” — and a movement was born. Cubist painters like Braque were interested in reducing their subjects to basic geometric shapes: A human body became a rectangle; the head, a square; and so on. But this was more than just a return to geometry class. The artists presented their subjects from multiple perspectives and viewpoints — often in the same painting — creating radically distorted forms like those that eventually made Pablo Picasso famous.

Surrealism

By the time World War I erupted in 1914, Sigmund Freud’s writings on the influence of the subconscious had taken off. So when European artists revolted by the ongoing collapse of society began looking for new ways to express themselves, they found it in the dreamlike void of their subconscious. Surrealists embraced their unconscious minds and tried to stir the hidden interior worlds of their audiences, like in “The Persistence of Memory” by Salvador Dalí. The movement’s name likely came from Guillaume Apollinaire, an artist who wrote in a 1917 letter, “I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism.”

Dada

Nobody is certain where the name for “Dada” originated, which is fitting: The art movement is hard to define. (As one story goes, a German artist slid a knife into a dictionary and landed on the word dada, a French term for a hobby horse.) Dada developed in the early 20th century as a reaction to the horrors of World War I, which many believed had defied all reason, logic, and rationality. To Dadaists, society’s attempt to make things “normal” again was just a ruse. They embraced the wacky, weird, and nonsensical. They revolted against conventions, traditions, and gatekeepers. They were irreverent and irrational — all in an attempt to shock people back into awareness of how the world really was. Notable works from the dada movement include “Bicycle Wheel” by Marcel Duchamp, “Ingres’s Violin” by Man Ray, and “Mechanical Head” by Raoul Hausmann.

Bauhaus

For centuries, artists were just ordinary people trained in a decorative craft. But Romanticism changed that by successfully elevating artisans to a higher plane. The Industrial Revolution further separated the “artistic world” from the so-called “practical world.” But starting around 1919, the Stattliches Bauhaus — a group of art and design schools in Germany — pushed to return art to its roots by merging it with the means of mass production. The aim of Bauhaus was to unify art with the everyday (think: metalworking, pottery, cabinetmaking), a mission reflected in the school’s slogan, “Art into Industry.” Practitioners in the world of architecture achieved great success during this movement. Bauhaus schools closed in 1933 due to political tension in Germany and the rising Nazi party, but the impact of the movement continued to live on. Bauhaus founder and architect Walter Gropius and student-turned-faculty-member Marcel Breuer went on to teach at Harvard Graduate School of Design, mentoring notable architects like I.M. Pei, Edward L. Barnes, and Paul Rudolph.