Cilantro

No other herb divides opinions quite like cilantro (known as coriander in the U.K. and some other English-speaking countries). For many people, the fresh, slightly citrusy herb is an essential ingredient, especially in Latin American, Indian, and Chinese dishes. Others despise cilantro, often suggesting it tastes like soap, a response that occurs in an estimated 3% to 21% of people.

The dramatic difference in perception is based on genetics. As John Hayes, a sensory expert and professor of food science at Penn State, explained to Live Science, “Nobody knows exactly which genes are involved in cilantro preference,” but studies suggest a specific olfactory receptor gene, OR6A2, may be the culprit. Most cilantro haters share this particular gene, which gives them the capacity to identify the smell of the herb’s aldehyde chemicals — chemicals that are also found in many dyes, perfumes, detergents, and soaps.

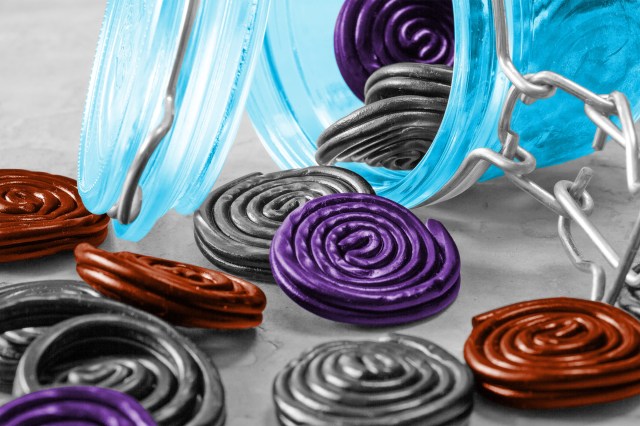

Licorice

Licorice is the common name of Glycyrrhiza glabra, a flowering plant that grows in parts of Asia and Europe. The root of the licorice plant contains glycyrrhizin, a sweet, aromatic compound used as a flavoring agent in black licorice confectioneries as well as in alcoholic drinks such as sambuca, pastis, and absinthe. It’s also found in medicines such as NyQuil, which explains why some licorice haters argue it tastes like medicine.

Unlike cilantro, no genetic explanations have yet been provided to explain some people’s aversion to licorice. But as Marcia Pelchat, an associate member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, told NBC News, “It’s not a learned like or dislike … it does seem to be something that people are born with.” Genetics, then, may well eventually be able to shed some light on why as many as 45% of Americans dislike black licorice.

Blue Cheese

Few dairy products polarize the public as dramatically as blue cheese, with its characteristic blue or green veins of mold. People tend to either delight in the complex, sharp flavors of cheeses such as Roquefort, Gorgonzola, and Stilton, or find them quite revolting — the strong smell alone can often provoke disgust.

Research suggests our brains are more reactive than our taste buds when it comes to our love or hatred for “stinky” cheeses. Researchers at the Université de Lyon found that in some people, the brain’s reward center displays aversion when confronted with strong cheeses. When asked to explain why they were disgusted by the cheese, six out of 10 respondents stated the odor and taste were enough to turn their stomachs. Fundamentally, this all has to do with the sensation of disgust — for some, the odor of decay some people sense in smelly cheeses is sufficient to provoke a disgusted response.

What’s more, the region of the brain that fires up when hungry people see food remains inactive in some people when they see or smell strong cheeses. The researchers at Université de Lyon observed that the ventral pallidum — a structure within the brain’s basal ganglia and a core structure of the reward circuit — is deactivated in some cheese haters. This suggests those who are disgusted by cheese may not perceive it as “food” at all — at least on a subconscious level.

More Interesting Reads

Okra

Though it’s often thought of as a vegetable, okra is technically a fruit, and a highly divisive one at that. Native to Africa and used extensively in Indian, Middle Eastern, Caribbean and Southern U.S. cuisine, okra’s most controversial characteristic is its distinctive texture.

When cooked, okra releases large amounts of mucilage, a gelatinous substance that makes the food useful as a thickener for broths and soups (gumbo being a prime example). For some people, okra’s slimy nature is a definite no-no, while others — especially those who have grown up with it — celebrate its distinctive mouthfeel and mild, grassy flavor. Okra is a good example of how texture, rather than flavor alone, can incite deeply divided opinions.

Marmite

Back in the late 19th century, a German scientist named Justus von Liebig discovered brewer’s yeast — traditionally used in the production of bread and beer — could be concentrated, bottled, and eaten. In 1902, the Marmite Food Company was founded to take advantage of this accidental discovery, using readily available yeast from the many breweries in the company’s hometown of Burton-on-Trent in England.

Marmite became popular in the U.K. during World War I, and from there it evolved into something of a national culinary icon. Fans continue to spread it on buttered toast and have learned to incorporate it into everything from pasta dishes to brownies. But not everyone can tolerate the dark brown paste with its intensely salty, yeasty, and slightly bitter flavor profile. The makers of marmite even embraced the polarizing nature of their product, as evidenced by the marketing slogan, “You either love it or hate it.”

Balut

Taste and texture are two of the main factors in why people have an aversion to particular foods. But the very concept of some foods, beyond their actual flavor or aroma, can also repel people. For example, take balut, a popular street food in parts of Southeast Asia, especially the Philippines. Balut is a fertilized duck egg containing a partially developed embryo, which is boiled and then eaten from the shell.

That description alone is enough to prevent many people from giving it a fair shot. But balut has many fans who relish the combination of savory soup, meaty bird, and warm yolk, all handily served in the shell and often accompanied by salt and vinegar. Balut is a prime example of how food is cultural: To those who’ve grown up with it, balut is entirely acceptable, but to many Westerners the very idea is enough to turn stomachs.

Durian

Durian is a large — sometimes soccer ball-sized — fruit with a thorn-covered husk that’s hugely popular in its native Southeast Asia, where it’s sometimes called the “king of fruits.” Fans point to the complex taste of its custard-like pulp, which Desiree Pardo Morales, founder and president of Tropical Fruit Box, described to Martha Stewart as “a mixture of vanilla, diced garlic with notes of pepper, and caramel mixed with whipped cream.”

Critics, however, focus primarily on its notorious odor — so obnoxious, powerful, and persistent that durian is banned in many hotels, airports, public transportation systems, and other enclosed public spaces across Southeast Asia. The smell is often likened to sewage or stale vomit. It’s safe to say, then, that durian is an acquired taste — if you’re brave enough to confront its stench.