The Official Colors Have Deeper Meanings

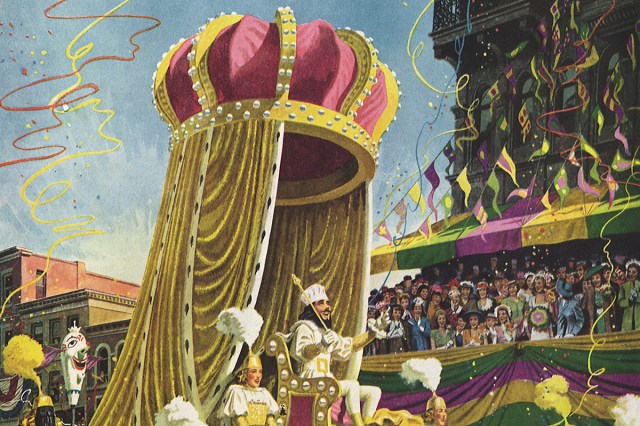

The three official colors of Mardi Gras are purple, gold, and green. The origin of these colors goes back to the first Rex parade, one of the oldest and most popular Mardi Gras parades, which was held in New Orleans in 1872.

Carnival historian Errol Laborde believes the colors were selected in keeping with the laws of heraldry, a medieval custom that dictates the design of flags, coats of arms, and other heraldic symbols. According to those laws, flags should contain three fields consisting of colors and metals (such as gold and silver), though the exact hues are left up to personal preference from there.

The Rex Organization — the group that founded the eponymous parade — has never publicly stated why purple, gold, and green in particular were chosen as the color of Mardis Gras. But we do know the colors were assigned specific meanings at the Rex parade held on Mardi Gras in 1892.

The theme of the parade was “Symbolism of Colors,” and each float displayed a color and its associated theme. At that event, the purple float represented justice, the gold float represented power, and the green float represented faith.

The First U.S. Celebration Was Held in Alabama

Before Mardi Gras came to the Americas, it was a popular celebration in Europe, especially among French Catholics, who brought the holiday with them to the United States. And although most Americans associate Mardi Gras with New Orleans, the first official recorded celebration in the United States took place in Mobile, Alabama.

On March 2, 1699, French Canadian explorer Jean Baptiste Le Moyne Sieur de Bienville and a team of explorers arrived 60 miles south of New Orleans on the eve of Mardi Gras. Given the timing of their arrival, they named the spot where they landed “Pointe du Mardi Gras.”

By 1702, Bienville had made his way east down the Gulf and established Fort Louis de la Louisiane along the Mobile River. That settlement came to be known as Mobile, and in 1703, a local Frenchman named Nicholas Langlois helped organize the first recorded Mardi Gras celebration in the United States.

Details of the festivities are sparse, but we do know that inaugural celebration predated the founding of New Orleans by 15 years, and Mardi Gras events didn’t become common in NOLA until the 1730s. Mardi Gras continues to be a beloved and well-attended tradition in Mobile today, attracting an estimated 1 million annual attendees (compared to the 1.4 million revelers who visit New Orleans).

Parades Are Organized by “Krewes”

In many parts of the U.S. where Mardi Gras is celebrated, official festivities are orchestrated by social clubs called “krewes.” Krewes are inspired by the Cowbellion de Rakin Society, a mystic society founded in Mobile in 1830. But the term didn’t exist until several decades later, when celebrants in New Orleans emulated their neighbors in Alabama and founded secretive societies of their own.

“Krewe” is an old-fashioned spelling of “crew,” and the term was coined no later than 1857 in New Orleans. Krewes are private clubs that primarily exist for the purpose of celebrating the Carnival season, especially Mardi Gras. Each year, those krewes work behind the scenes to plan parades and other festivities.

That work involves making colorful floats, designing elaborate costumes, and hosting various parades or balls in the two-week period leading up to Mardi Gras. Krewes are also tasked with electing the Rex (king) each year, whose lavish parade serves as the climactic event that caps off the year’s Mardi Gras festivities.

The oldest recorded krewe is the Mistick Krewe of Comus, whose origins in New Orleans date back to 1857. That year, the group paraded through the streets wearing costumes, establishing a new standard that other krewes adopted. Today, the oldest and largest of NOLA’s truck float krewes is the Krewe of Elks Orleans. Founded in 1935, they roll out 50 individually designed truck floats and 4,600 riders for their annual parade.

More Interesting Reads

There Are Strict Parade Rules

While everyday attendees are welcome to celebrate Mardi Gras in New Orleans however they please, parade participants must abide by a strict set of rules. During Mardi Gras, float riders are mandated to wear festive masks during parades. In Jefferson Parish (located in the Greater New Orleans area), anyone who removes their mask may be banned from the parade and is subjet to fines of up to $500.

New Orleans also prohibits the commercialization of any krewe-organized Mardi Gras parades. Displaying corporate logos on the float and throwing advertisements into the crowd are some of the more common violations the city has cracked down on. This rule exists to maintain the parade’s artistic integrity and annual theme.

More recently, there’s been a push to remove plastic beads from celebrations in the name of environmental sustainability. In 2025, the Krewe of Freret became the first New Orleans krewe to ban plastic beads from events, with the goal of eliminating the 200,000 sets of beads estimated to end up in trees, storm drains, and landfills each year.

It’s Just One Part of the Carnival Celebration

Mardi Gras marks the end of a weeks-long period of revelry known as Carnival. This festive season begins on the Christian holiday Twelfth Night, which traditionally falls on January 6. It runs all the way until Mardi Gras — which can fall as early as February 3 or late as March 9 — meaning Carnival can be as short as 29 days and as long as 64 days (on leap years).

Mardi Gras, which means “Fat Tuesday” in French, falls on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, the Christian holiday that marks the end of the celebrations and the start of Lent, a 40-day period of fasting and prayer.

In the days before the Mardi Gras parades begin, people in New Orleans and other areas that observe Carnival celebrate in other ways. Local organizations in the Big Easy are known for their streetcar parades, and the Krewe of Joan of Arc parades through town donning medieval garb on January 6 in honor of the French heroine’s birthday.

There are generally dozens of themed parades and fancy balls, as well as the copious consumption of King Cake, a colorful treat served at bakeries throughout New Orleans, with similar variations also served in Latin America and parts of Europe. In the U.S. and Latin American traditions, each cake contains a tiny plastic baby concealed inside to honor the birth of Jesus Christ.

In France, cakes typically contain a bean or coin, and the Portuguese hide a dried fava bean inside. Whoever finds the hidden item in their slice of cake is typically responsible for buying the next King Cake or hosting the next celebration.