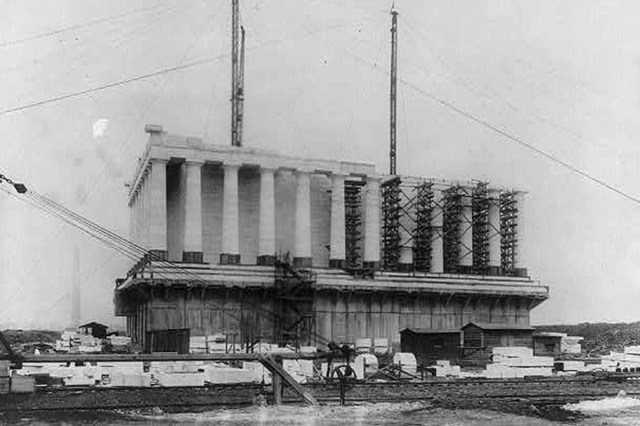

It Was Inspired by the Parthenon

The architectural style of the Lincoln Memorial, which was completed in 1922, is notably different from the typical style of the early 20th century. New York architect Henry Bacon took a unique yet meaningful approach to the monument’s design, modeling it after the Parthenon in Athens, Greece.

Bacon believed the design should reflect Lincoln’s values. According to the National Park Service (NPS), Lincoln’s lifelong passion for and defense of democracy inspired Bacon to draw from the architecture of ancient Greece, the birthplace of democratic ideals.

All told, the memorial measures 190 feet long, 120 feet wide, and 99 feet tall. Bacon chose to use various types of stone for his design. The exterior and upper stairs are constructed from Colorado marble, while the accents were sourced from other states; the terrace is made from Massachusetts granite and the chamber floor uses Tennessee pink marble.

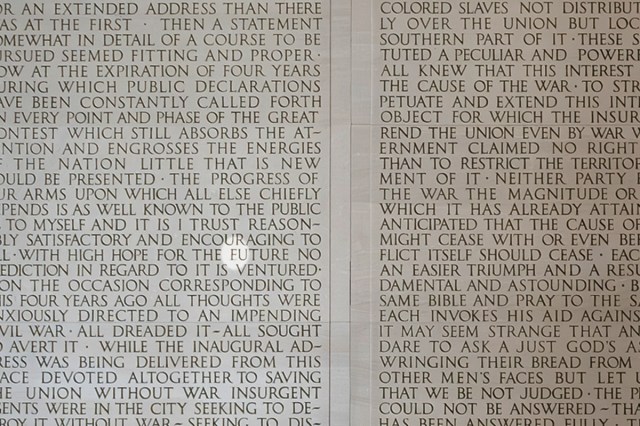

There Was a Typo in the Inscription

The inside of the Lincoln Memorial features several important inscriptions, but the one on the north interior wall is particularly interesting. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address from 1865 is carved into the chamber’s limestone —and if you look closely you can see that one of the words was originally misspelled..

While speaking of national reconciliation after the Civil War, Lincoln said, “With high hope for the future no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” But the engraver made an error when translating this sentiment to the wall. When engraving the word “FUTURE,” artist Ernest C. Bairstow — who expertly completed all the other lettering and small details on the memorial — inadvertently carved a capital “E” at the beginning of the word, resulting in “EUTURE.”

According to the NPS, the mistake was likely the result of using an “E” stencil rather than an “F.” Though the error has since been corrected by filling in the bottom line of the letter to revert it to an “F,” the shadow of the “E” is still visible if you look for it.

Its 36 Columns Have a Special Meaning

The most prominent exterior feature of the Lincoln Memorial are the 36 towering Doric columns, each standing 44 feet tall with a base diameter of more than 7 feet. And the number of columns is no coincidence — it’s symbolic. Architect Henry Bacon chose to surround the memorial with 36 columns to represent the 36 states in the U.S. at the time of Lincoln’s death on April 14, 1865.

By the time the memorial was completed in 1922, there were 48 states in the nation. (Alaska and Hawaii weren’t granted statehood until 1959.) And the newer states aren’t overlooked by the design. Inscribed at the top of the memorial, above the exterior columns, are the names of the 48 contiguous U.S. states, and in 1976, a plaque honoring Alaska and Hawaii was added to the plaza as well.

More Interesting Reads

The Current Site Was Once in the Potomac River

The site of the Lincoln Memorial and much of the surrounding area were once buried beneath the Potomac River and its marshy shores. The site was called Kidwell Flats — an especially muddy portion of the river.

The original plans for the National Mall were drawn up in 1791 and ended at the Washington Monument, at the edge of the Potomac’s original shoreline. To the west was swampy marshland, known for being buggy, musty, and unpleasant. However, city planners wanted to add more land to the National Mall’s total area, so a plan was devised to make that marshland more hospitable.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the Potomac during the 1880s and ’90s, dumping soil west and south of the Washington Monument. Today, that area is not only home to the Lincoln Memorial but also to the World War II Memorial, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial, among other landmarks.

The Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool was also built atop this dredged soil. Constructed during the 1920s, the original pool lacked pilings to support it, so it sank about a foot into the marshy land below. That slow sinking caused cracks and leakage, subsequently requiring about 30 million gallons of water each year to refill.

Since its construction, the landmark has undergone several renovations. In 2012, it received a complete overhaul, featuring a restored bottom and a new sustainable water system.

There’s Going To Be a Museum Underneath the Memorial

It’s a question NPS guides get all the time: “What’s underneath the Lincoln Memorial?” For the last century, the answer has been quite boring: an empty basement.

Despite a widely held myth that the late president is buried beneath his memorial (he was actually laid to rest in Springfield, Illinois), the monument’s so-called “undercroft” is relatively empty. The cavernous, bunker-like structure features massive concrete columns and graffiti left behind by its original builders.

But that’s all about to change: An immersive museum featuring 15,000 square feet of public exhibit space is set to open in July 2026. The exhibits will illuminate the monument’s history, its construction, and its role in civil rights demonstrations.

The undercroft spans 43,800 square feet in total, meaning only part of it will become museum space. Floor-to-ceiling glass walls will allow visitors to view the undeveloped section of the monument’s concrete foundations, offering a rare behind-the-scenes look at one of America’s most enduring symbols.