Heinz Tomato Ketchup Has a “Speed Limit”

Heinz is one of the biggest ketchup producers in the world, and its iconic glass bottles can be found in supermarkets and restaurants worldwide. The condiment itself actually has a “speed limit” — a maximum flow rate of .028 miles per hour set by the company as an indicator of the product’s thick consistency.

Each batch of ketchup is tested in a device Heinz calls a “quantifier,” which measures how far the product flows over the course of 10 seconds. If the ketchup travels too fast, indicating it isn’t sufficiently thick or doesn’t have the ideal texture,, it’s not released to the public.

In 2021, Heinz partnered with Waze and Burger King as part of a marketing campaign to reward drivers stuck in traffic with a free Impossible Whopper. Anyone forced to travel at the measly rate of 0.028 mph due to traffic was given redemption details in the Waze app.

And in 2023, Heinz released the “Slowmaster 57” in conjunction with the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. Playing off the idea of race cars speeding at hundreds of miles per hour, this specially designed mini racetrack ramp invited people to test out the famous slowness of Heinz ketchup for themselves.

Tomatoes Originated in South America

Though many people associate tomatoes with Italian cuisine today, they were originally cultivated in the Andes region of South America, though there are competing theories regarding the fruit’s precise lineage. Some believe the 10,000 modern tomato varieties can be traced to a pea-sized fruit native to parts of northern Peru and southern Ecuador called Solanum pimpinellifolium — also known as “pimp” — which was cultivated some 7,000 years ago.

However, a 2020 study indicates the timeline should be pushed further back to 80,000 years ago, when cherry-sized tomatoes may have been grown in Ecuador. In either case, these smaller tomato plants migrated to Mesoamerica, which is where tomatoes were first domesticated an estimated 7,000 years ago.

It wasn’t until European explorers came to the Americas that tomatoes were introduced to the European continent. Sixteenth-century Spanish explorers encountered what the Aztecs referred to as tomatl (“plump fruit”), and returned to Spain with the treat in tow. Tomatoes were introduced to Italy via Spain no later than 1544 — the date of the earliest known printed reference to tomatoes, from Italian physician Pietro Andrea Mattioli.

Europeans Thought They Were Poisonous

When tomatoes first made their way to Europe, they weren’t exactly considered a culinary delicacy. In fact, they earned a frightening and unwarranted reputation for being toxic and were hence dubbed “poison apples.”

It’s long been theorized that this unsavory reputation stems from reports of wealthy Europeans falling ill after eating tomatoes served on pewter plates, which contain lead. Given tomatoes are highly acidic, the acid would leach the lead from the plate, leaving the consumer with lead poisoning.

However, author Joe Schwarcz argues in the Montreal Gazette that this oft-repeated lead theory is just a myth. Schwarcz claims the idea that tomatoes were poison likely stemmed from tomato plants being erroneously classified as deadly nightshades by uneducated herbalists. Tomato plants visually resemble the belladonna bush, whose fruits were known to be toxic, and so tomatoes were believed to be the same.

It was only around the late 1800s that European society began to view tomatoes as tasty, nontoxic treats. Tomatoes were normalized in part due to the 1880s invention of the modern pizza in Naples, Italy. This plus the 1897 debut of Campbell’s condensed tomato soup helped popularize tomatoes in the culinary world, and the fruit earned a far more favorable reputation.

More Interesting Reads

The Supreme Court Ruled Them To Be Vegetables

In 1893, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case Nix v. Hedden, which debated whether tomatoes should be classified as fruits or vegetables for taxation purposes. This all came to pass after the Tariff of 1883 took effect, which imposed a 10% tariff on any imported vegetables. Imported fruits, however, were deemed tax-free.

Tomatoes are indeed fruits in a botanical sense, because they meet two important criteria: They contain seeds and they grow from flowering plants. But many people viewed tomatoes as vegetables based on the way they were cooked and eaten, including Edward Hedden — the tax collector for the Port of New York.

It’s unknown whether Hedden didn’t realize tomatoes were technically fruits or simply chose to ignore that fact, but in either case he imposed the 10% tariff on the food. Manhattan-based wholesaler John Nix & Co. found this out the hard way when it was taxed on a shipment of tomatoes from the Caribbean. Nix argued tomatoes should be taxed like the fruits they are and subsequently sued Hedden.

In 1893, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Hedden’s favor, claiming that despite technically being fruits, tomatoes were more commonly treated as veggies by the general public and should therefore be taxed as such. Justice Horace Gray wrote in his opinion, “Botanically speaking, tomatoes are the fruit of a vine … But in the common language of the people, whether sellers or consumers of provisions, [tomatoes] are vegetables.”

Tomato Juice Is the Official State Drink of Ohio

Before 1965, no U.S. state had an official state drink. But that changed on October 6 of that year, when the Buckeye State adopted Senate Bill 92, which stated, “The canned, processed juice and pulp of the fruit of the herb Lycopersicon esculentum, commonly known as tomato juice, is hereby adopted as the official beverage of the state.” While other states have since declared official beverages of their own (with milk being the most popular choice) Ohio remains the only state to name tomato juice as its official beverage.

This choice paid homage to the state’s thriving tomato industry; at the time, Ohio was the second-largest producer of tomatoes in the nation behind California. It was also a native Ohioan named Alexander Livingston who helped popularize tomatoes nationwide. In 1870, Livingston — a horticulturist by trade — developed the “paragon,” the first commercially successful variety of tomato in the U.S., and his hometown of Reynoldsburg continues to host an annual tomato festival dedicated to his legacy.

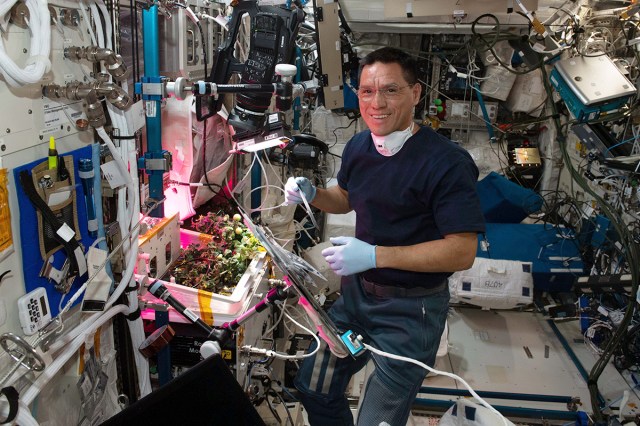

A Tomato Went Missing in the International Space Station

In March 2023, astronaut Frank Rubio harvested what’s considered to be the very first tomato grown in space. The fruit was grown as part of the eXposed Root On-Orbit Test System (XROOTS) — a test program to determine the feasibility of growing produce for astronauts to enjoy in space.

Rubio grew the historic tomato on the International Space Station, though after harvesting, he subsequently misplaced the fruit. After 20 hours of searching, Rubio gave up and assumed the tomato had been lost forever. But that December, astronauts successfully recovered the lost tomato after eight long months of wondering where it could have gone. Though dehydrated, slightly squished, and mildly discolored, the fruit was in otherwise okay shape without any fungal growth.

A 20,000-Person Tomato Fight Is Held Each Year in Spain

La Tomatina is an annual festival in which attendees pelt each other with tomatoes — colloquially known as the “world’s biggest food fight.” The event occurs each year on the final Wednesday in August in the Spanish town of Buñol, located roughly 25 miles west of Valencia.

While the town’s permanent population is just 9,000 people, as many as 50,000 revelers have participated in La Tomatina at its peak. The number of ticketed participants was capped at 20,000 in 2013, which is where it remains today.

The festival began in the 1940s, though it was temporarily banned in 1956 by the city council amid pressures from Francisco Franco’s dictatorial regime to disallow unauthorized celebrations. However, La Tomatina returned in 1957 in the form of a parodic “Burial of the Tomato” funeral procession, which instilled a deep sense of community in its participants. Due to mounting local pressure, the tradition was officially recognized as a city festival in 1959, with a more rigid organizational structure.

An estimated 330,000 pounds of tomatoes are hurled during the food fight each year, which are brought to the town by six loaded trucks. Organizers also make a point of limiting food waste by only using tomatoes that have been deemed unfit for consumption and would’ve otherwise been thrown out.