Silly String

Silly String may be a nostalgic party staple now, but it was originally a medical product. In the 1960s, chemist Robert P. Cox and inventor Leonard A. Fish set out to create an instant spray-on cast for broken bones. During their experiments, which included testing upward of 500 different spraying vessels, they discovered the material could be sprayed in long, sticky strands from a certain pressurized can.

The pair saw the potential in their silly substance and brought it to California toy company Wham-O, home to such popular toys as the Frisbee and the Slip ‘N Slide. The meeting didn’t exactly go as planned. Cox and Fish excitedly demonstrated the spray to — and on — the Wham-O employee, and they were subsequently asked to leave.

The following day, however, the eager inventors were asked to send 24 cans to Wham-O for a second look. Despite being reformulated over the years to comply with changing regulations — notably the 1978 U.S. ban on Freon as a propellant — Silly String has remained a staple on store shelves ever since. According to Cox’s 2008 obituary, he couldn’t help but feel a bit frustrated that, of all his endeavors, it was his silliest invention that ultimately took off.

Play-Doh

Anyone who’s cleaned Play-Doh out of carpet or picked up all its little crumbs knows how messy it can be, so it may come as a surprise that it was originally used as a cleaner. In the 1930s, Cincinnati-based soap manufacturer Kutol began making its own version of a doughy putty used to remove soot from wallpaper. This was a common need at a time when homes were still primarily heated by coal furnaces, and after Kroger stores agreed to carry Kutol’s wall cleaner, the once-struggling company found new footing. But by the end of World War II, homes largely switched to gas and oil heating, and demand for the cleaner began to wane.

By the 1950s, the company had yet again fallen on tough times. But its fate turned once more after a Kutol executive’s sister-in-law, Kay Zufall — who also happened to be a nursery school teacher — suggested repurposing the dough as a children’s toy.

With a few tweaks to the formula and the introduction of bright red, blue, and yellow colors, the rebranded product was launched as Play-Doh. It was first sold to Cincinnati schools in single-gallon cans; three-packs of smaller jars were introduced for retail sale in 1956. It was a smash hit: By 1958, the company, which just four years prior was barely cracking $100,000 in annual sales, was raking in nearly $3 million yearly. In the mid-2010s, it was estimated that more than 3 billion cans of the stuff had been sold around the world since its debut as a toy.

Listerine

Listerine’s minty burn wasn’t always meant to freshen breath. When the product was created in 1879 by surgeon Joseph Lawrence in St. Louis, Missouri, it was intended as a surgical antiseptic. Its name was even an homage to British surgeon Joseph Lister, who pioneered sterile surgery in the 1860s.

In the 1880s, Lawrence was working with pharmacist Jordan Wheat Lambert to sell the product. Doctors sang its praises, claiming it effective against everything from ulcers to gonorrhea. By the 1890s, Listerine was officially being marketed for uses beyond the doctor’s office, primarily to dentists as a “perfect tooth and mouth wash,” as advertisements of the time touted.

Throughout the ensuing years, Listerine’s uses varied. At different times it was marketed as a floor cleaner, a cure for dandruff, and even an elixir for sore throats, coughs, and colds — it was only in 1975 that the U.S. Federal Trade Commission ordered the company to stop falsely claiming that health purpose.

Its most lucrative market, however, was established in the 1920s, when the Warner-Lambert pharmaceutical company began advertising Listerine to treat “halitosis,” aka bad breath. Listerine’s ads painted this fairly minor affliction as a troublesome medical condition for which they had the cure. The campaign was so successful that not only did Listerine emerge and remain best known as a mouthwash, but the phrase “halitosis appeal” became standard marketing speak to refer to the use of fear to sell a product.

More Interesting Reads

Treadmills

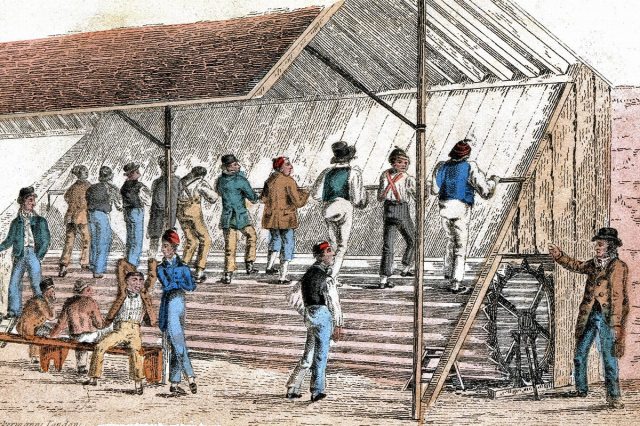

We know treadmills as a modern fitness staple that, depending who you ask, are more pain than pleasure. This is somewhat fitting, given the exercise tool’s punishing origins. In the early 19th century, British engineer William Cubitt designed the first treadmill as a form of prison labor. Inmates, often in groups, were forced to walk on large rotating wheels for upward of eight hours a day. The wheel power was typically used to grind grain or pump water, supposedly making it a productive means of punishment designed to rehabilitate prisoners.

By the early 20th century, treadmills had been abandoned in prisons. But as heart disease started to skyrocket in the U.S., doctors began rethinking the machine, first as a testing tool for cardiovascular performance.

American doctor of medicine Kenneth Cooper used treadmills in the 1960s to test endurance in pilots, and in 1968, his book Aerobics promoted running as a way to prevent heart disease. The work inspired New Jersey engineer William Staub, who built his own treadmill — a simple, compact motorized machine — and in the 1970s, his PaceMaster treadmill brought indoor running to the masses.

Rogaine

Rogaine has long been a popular hair loss treatment, but that use was discovered as a happy side effect of another drug. Its evolution began in the 1950s, when chemists at the Upjohn pharmaceutical company — also responsible for developing Xanax and Motrin before being acquired by Pfizer — developed a drug called minoxidil to treat ulcers, which was later found to lower blood pressure. In the 1970s, the FDA approved minoxidil as an oral blood pressure medication, and patients who took the drug began noticing increased hair growth as well.

As the unexpected side effect became more widely known, Upjohn acted before competitors could, refining minoxidil into a topical solution. In 1988, the FDA approved the newly named Rogaine as a prescription first for men and eventually for women (three years later). In 1996, Rogaine became available over the counter.

When it was initially released, there was some skepticism about whether the product could live up to the hype — it wasn’t a miracle cure for hair loss, after all. Upjohn focused on marketing directly to consumers instead of doctors, namely with aggressive television and magazine campaigns. As a result, sales grew from around $67 million in 1989 to $140 million in 1990. As of 2020, an estimated 2.87 million Americans counted themselves as Rogaine customers.