How Do Polygraph Tests Work?

Polygraph machines don’t detect lies directly. Instead, they record several physiological indicators simultaneously, including blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, perspiration, and skin conductivity — physiological responses that are typically involuntary.

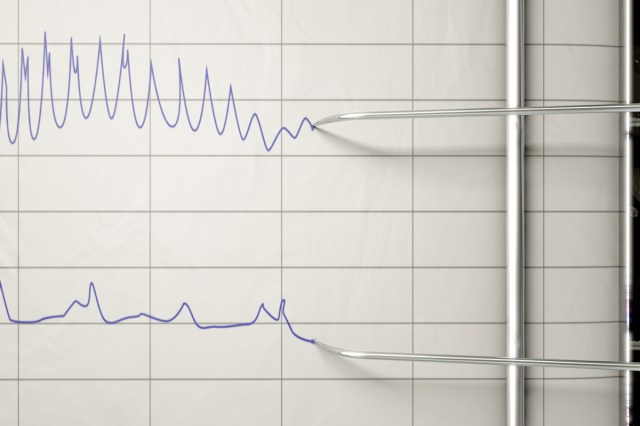

During the test, the examiner asks a series of questions, usually a combination of control questions designed to establish baseline responses and questions directly relevant to the issue being investigated. The subject is fitted with a number of sensors to measure their bodily responses, which are then recorded on graph paper, providing a visual representation of the subject’s physiological state.

The basic theory behind the polygraph is quite straightforward: When people lie, they experience psychological stresses that manifest in measurable physiological changes. For example, a person may breathe more rapidly, sweat more profusely, or experience an elevated heart rate when lying about potentially incriminating details. Those are measured and compared against a subject’s truthful baseline responses, and the examiner then analyzes the responses to tell — in theory, at least — when the subject has been truthful or dishonest.

How Accurate Are the Tests?

One of the fundamental issues with polygraph tests is the lack of any unique physiological signature for lying. According to the American Psychological Association, “There is no evidence that any pattern of physiological reactions is unique to deception. An honest person may be nervous when answering truthfully and a dishonest person may be non-anxious.”

Our bodies can respond to stress, anxiety, fear, and even cognitive effort in similar ways regardless of whether or not we’re being deceptive — for instance, an innocent person terrified of being falsely accused could display the same physiological responses as a guilty person attempting to conceal the truth.

Proponents of polygraph testing often cite studies that suggest polygraphs are accurate between 80% and 90% of the time. Many of those studies, however, have involved people lying about clearly defined events in controlled experiments.

A 2008 study by the University of Utah’s Department of Educational Psychology, for example, recruited 120 people from the general community to take part in a mock crime experiment in which they took polygraph tests – with 86% of the innocent participants and 93% of the guilty participants correctly classified. But in real-life circumstances, it’s likely that polygraphs are significantly less accurate, particularly when taking false positives into account.

Researchers have found that polygraph tests produce more false positives (innocent people who wrongly fail) than false negatives (guilty people who wrongly pass). One collation of field studies suggested the false positive rate of innocent people identified as deceptive through polygraph testing was as high as 19%.

Other factors are also in play when it comes to the validity of polygraph results. Certain techniques — ranging from controlled breathing to deliberately making yourself feel upset and confused — may help people pass tests even when they’re lying.

And an examiner’s own ability can influence the efficacy and validity of polygraph results: An experienced examiner may spot attempts to beat the test that a novice could potentially miss. It’s because of these various limitations that the American Psychological Association states, “Most psychologists and other scientists agree that there is little basis for the validity of polygraph tests.”

When and Where Are Polygraphs Used?

Given the limitations of polygraph tests and the widespread concerns regarding their reliability, polygraph results are often inadmissible as evidence in criminal trials. In the United States, polygraph admissibility varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, with some states banning it completely while others allow results by stipulation (often under specific circumstances when both parties agree).

However, polygraphs remain widely used in pre-employment screening for law enforcement, intelligence agencies, and other sensitive government positions, typically to assess a person’s trustworthiness and to identify potential threats. Recently, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Defense have turned to polygraphs to help root out potential intelligence leakers — although not without complaint and controversy.

Outside of government, things are different. In the U.S., the Employee Polygraph Protection Act (EPPA) prohibits most private employers from using lie detector tests, either for pre-employment screening or throughout the course of employment. So while polygraphs can be useful in certain limited circumstances, the notion of the infallible “lie detector” of pop culture fame is largely the stuff of fiction.