A History of Big Bills

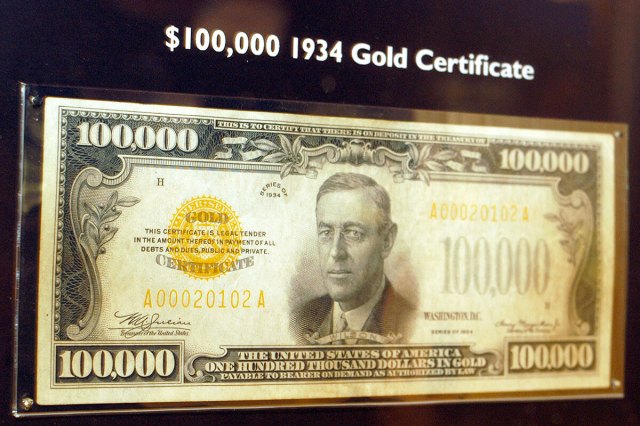

The United States used to print currency in denominations that would seem extreme to most modern-day citizens. The highest value note ever issued by the federal government was the $100,000 gold certificate. Printed between December 1934 and January 1935, it was meant to be used only for official transactions between Federal Reserve Banks and was never circulated among the general public — it was even illegal for a private individual to own one.

The gold certificate remains something of an anomaly, but several other high-value notes were widely circulated for much of American history. There was a $500 bill featuring President William McKinley, a $1,000 note featuring President Grover Cleveland, a $5,000 bill with President James Madison, and a whopping $10,000 bill that bore the lesser-known visage of Salmon P. Chase, who served as Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury from 1861 to 1864.

All these notes were last printed in 1945 and were later discontinued (no longer issued) in 1969. They remain legal tender even now, but the ones still in circulation today are likely in the hands of private numismatic dealers and collectors. The rarest of these notes are worth a lot of money — in 2019, a rare $1,000 bill from 1891 was valued at between $2 million and $3 million. So if you do ever come across one of these notes, do not use it at face value — it’s probably worth a lot more as a collector’s item.

The 1969 Decision

On July 14, 1969, the Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve System announced that currency notes above $100 would be discontinued immediately due to lack of use. A couple principal factors drove this decision. First, these large bills had served a practical purpose up until the mid-20th century, primarily used for large bank transfers, real estate transactions, and settlements between financial institutions. But the rise of electronic banking and wire transfers, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, reduced the need for physical currency in large denominations — and electronic transfers were faster, safer, and more efficient anyway.

Secondly, then-President Richard Nixon was justifiably concerned that large bills made it easier for criminals to launder money and conceal large sums of illicit cash. A single briefcase, for example, could hold millions of dollars in $1,000 or $10,000 notes, creating a convenient vehicle for money laundering, tax evasion, and other financial crimes. Even to this day, high-denomination notes are often viewed as a security risk around the globe. As recently as 2016, the European Central Bank began phasing out the €500 note (equivalent to about $542) — a bill nicknamed the “Bin Laden” because of its association with money laundering and terror financing.

The lack of high-denomination bills in America today aligns with global anti-money-laundering efforts and the rise of digital transactions. So for now, at least, the $100 bill will remain the highest denomination banknote available in the United States, keeping those Benjamins at the top of the pile when it comes to paper money.