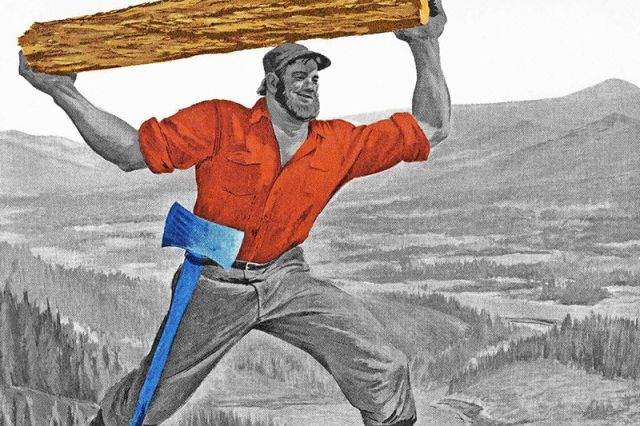

Paul Bunyan

Few creations can match the prowess of Paul Bunyan, the titan of the North Woods who palled around with Babe the Blue Ox and was responsible for the formation of landmarks such as the Grand Canyon and the Great Lakes. For all the obvious hyperbole, the character may have been based on the real-life French Canadian lumberjacks Bon Jean and Fabian Fournier, the latter better known by the workers who traded tales at logging camps in the late 1800s.

Bunyan stories first appeared in print just after the turn of the century, but it was a marketing campaign by the Red River Lumber Company that introduced the behemoth woodsman to the masses during World War I. Collected stories soon appeared in book form, establishing a mythical mainstay that remains larger than life through the monuments in his honor that populate the northern landscape.

Davy Crockett

There’s no question that Davy Crockett, a three-term U.S. congressman from Tennessee, was a real man, if not the “half horse, half alligator” he allegedly claimed to be. Regardless, the folksy, bear-hunting lawmaker with scant formal education was an anomaly among his well-bred peers and was already a celebrity by the time the first Davy Crockett’s Almanack appeared in print in 1835.

The legend received another jolt when he was killed at the famed 1836 Battle of the Alamo, and by the 1840s, the Almanack was featuring more outlandish stories of its hero handily fighting off bears and alligators. Still, Crockett may well have faded into memory, were it not for his mid-1950s revival by way of the Disney TV series and movies that had children everywhere wearing coonskin caps and singing about the “king of the wild frontier.”

Johnny Appleseed

The black sheep of the American folklore canon, Johnny Appleseed achieved immortality not through acts of cunning or bravery, but by way of his ragtag clothing and peaceful rapport with all living creatures as he scattered his wares across the land. Ironically, the man behind the myth — John Chapman — did display immense courage, fortitude, and resourcefulness by traipsing thousands of miles across the eastern wilderness and establishing orchards to aid settlers in the first half of the 1800s.

A zealous proponent of the Church of the New Jerusalem who had no permanent home and largely refused to sleep indoors, the eccentric Chapman was already famous by the time he died in 1845. But his fame lived on through the exaggerations that became associated with his memory via the written “recollections,” poems, and children’s stories that circulated in the decades afterward.

More Interesting Reads

Mike Fink

Another flesh-and-blood man who saw his celebrity swell as the frontier mythos gained steam, Mike Fink earned renown as a keelboatman on the mighty Mississippi River in the early 1800s. Tall and powerful, he allegedly boasted he could “outrun, outshoot, throw down, drag out, and lick any man in the country,” though his brashness and heavy-drinking ways may well have contributed to his death in 1823.

Five years later, the first Fink tale appeared in The Western Souvenir, giving rise to several decades’ worth of stories that focused more on his reputation for practical jokes than shows of strength. While his legend dimmed by the end of the century, Fink also received a lifeline from Disney when he was presented as the arch-foe-turned-ally in 1956’s Davy Crockett and the River Pirates.

Pecos Bill

The personification of the rough-and-tumble cowboy who tamed the Old West, Pecos Bill supposedly was raised by coyotes, single-handedly invented the modern methods of ranching, and could be seen riding a cyclone when not astride his bucking horse, the Widow-Maker. Such an indomitable character was no match for any enemy, though at least one account says the end came after he saw a Yankee dressed as a cowboy and laughed himself to death.

The first published Pecos Bill stories appeared around World War I from the hand of Edward O’Reilly, who insisted he heard the outlandish tales as a child, though historians have since thrown that claim into doubt. Whatever his origin, Pecos Bill’s adventures are more than wild enough to earn him a distinguished place in the tall-tale pantheon.

John Henry

One of the few Black heroes of American folklore, John Henry was said to be the strongest steel driver toiling on the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in the 1870s. When a steam-powered drill was introduced, Henry took it as a challenge to demonstrate man’s superiority over machine, winning the duel but working himself to death in the process.

As with other legends, historians have sought to uncover the source of the tale, with some claiming to have pinpointed a real John Henry and others determining that he was a composite of the anonymous hands who undertook the backbreaking labor. Regardless, his story struck a chord with audiences through the printed page and screen, and especially through the African American blues tradition that gave rise to work songs like “The Ballad of John Henry.”

Old Stormalong

A Bunyanesque character for the seafaring set, Old Stormalong stood 30 feet tall, according to some accounts, tangled with the Kraken of Norse mythology, and commanded a ship so large it had hinged masts to avoid colliding with the moon. It’s unknown who — if anybody — served as the model for the character, whose origins trace back to North Atlantic sea shanties of the 1830s and ’40s. While those early work songs presented “Old Stormy” as more of an everyman sailor, it was Frank Shay’s Here’s Audacity! American Legendary Heroes (1930) that brought him to life as a titanic superman of the surf, clearing the decks for his inclusion among the famous outsized figures of the genre.

Big Mose

As opposed to his rural counterparts, Big Mose was a hero of urban origins: A firefighter in New York City’s Bowery district, he supposedly stood 8 feet tall, boasted hands the size of Virginia hams, and uprooted streetcars and lampposts with ease. Once again, this was a character inspired by a legitimate person, a volunteer fireman, printer, and brawler named Moses Humphreys. And while the oral recounts were codified through the works of Ned Buntline, the Mose legend took root through a series of wildly popular stage plays in the 1840s and ’50s. Big Mose may not be as well known today as Davy Crockett and Johnny Appleseed, but his myth was every bit as formidable as the others’ during his pre-Civil War heyday.