City Lights (1931)

You can’t tell the story of cinema without Charlie Chaplin, whose Little Tramp remains one of the most enduring silver-screen characters ever created. A bittersweet romp in which the Tramp falls in love with a blind woman who works at a flower shop, it’s best remembered for what many (including yours truly) consider the best movie ending of all time.

Gone With the Wind (1939)

Still the highest-grossing movie of all time when adjusted for inflation, Gone With the Wind has been rereleased, reappraised, and rewatched more than any film ever made. You could argue, as many have, that Victor Fleming’s epic Civil War drama is an antiquated relic that belongs in a museum rather than a movie theater, but you can’t deny its influence.

In one of the earliest polls of its kind, Variety asked more than 200 film industry professionals to name the best film ever made. Gone With the Wind topped that list, as it has many others — albeit not recently, as its reputation has withered with age.

The Rules of the Game (1939)

Perhaps no country takes cinema more seriously than France, which has produced countless masterpieces since George Méliès and the Lumière brothers helped innovate the “seventh art” in the 1890s. At the top of that mountain of movies would have to be Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, a tragicomic parable for the inevitable-in-hindsight leadup to World War II.

No other movie has snagged a spot in the top 10 of Sight and Sound’s decennial poll of the greatest movies in history for all of its six editions: 1952, 1962, 1972, 1982, 1992, 2002, and 2012. It’s also been named the greatest French film ever made by Time Out, which, while accurate, is also somehow limiting — like the global conflict it presaged, The Rules of the Game transcends boundaries.

More Interesting Reads

Citizen Kane (1941)

“Seeing it,” film critic Archer Winsten wrote of Citizen Kane when it was first released, “it’s as if you never really saw a movie before.” More than 80 years later, Orson Welles’ all-timer has lost none of its power.

A true before-and-after moment in cinema, Citizen Kane marked the arrival of one of the most skilled, idiosyncratic filmmakers in Hollywood history: Welles produced, directed, co-wrote, and starred in his debut feature, which famously did not win Best Picture but has since gone on to be named the greatest movie ever made on countless occasions. You have to see it to believe the hype.

Casablanca (1942)

“If there is ever a time when they decide that some movies should be spelled with an upper-case M,” Roger Ebert wrote in the introduction to his list of the 10 greatest movies ever made, “Casablanca should be voted first on the list of Movies.”

The Library of Congress seems to agree, as Michael Curtiz’s World War II drama was added to the National Film Registry’s inaugural class in 1989. It also won the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay following its initial release. If you still haven’t seen it, it’s time to do so at least once, for old times’ sake.

Tokyo Story (1953)

The films of Yasujirō Ozu are quiet in their profundity, like a wise relative whose lessons you don’t fully understand until reconsidering them as an adult. There’s no wrong way to start with his imposing filmography, but there’s only one zenith: Tokyo Story, a moving family drama about an elderly couple who come to stay with their adult children in Japan’s capital. It’s sad, transportive, and, according to 359 directors, the greatest movie ever made.

Seven Samurai (1954)

Many people’s initial reaction to a black-and-white Japanese movie from the 1950s with a runtime of 207 minutes may be that it sounds like a chore, but in this case, nothing could be further from the truth. Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai is an epic in the truest sense of the word, a thrillingly melancholy exploration of honor, duty, and a bygone way of life that has proved one of Japanese cinema’s most enduring backdrops. (It also invented the assembling-the-team trope that has since been endlessly repeated ever since.)

You could populate an entire best-of list just with Kurosawa pictures alone, but Seven Samurai remains his most expansive, fully realized work — hence why it’s been hailed as everything from the greatest foreign-language film to the greatest action movie of all time.

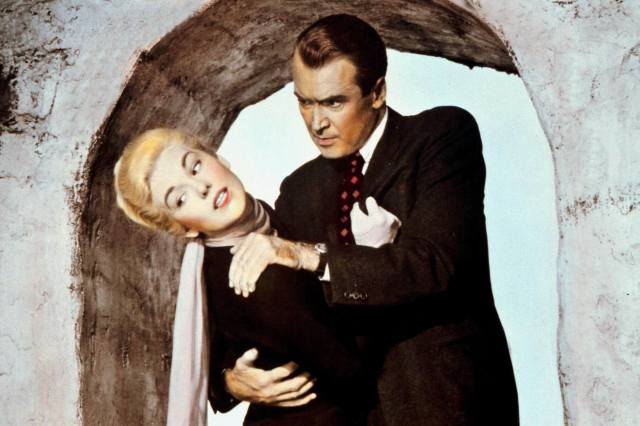

Vertigo (1958)

It took six decades for Citizen Kane to be dethroned on the aforementioned Sight and Sound poll. When that finally happened in 2012, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo was the usurper.

The kind of thriller only the Master of Suspense could have made stars Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak as a former detective and the woman he becomes obsessed with, respectively. In addition to creating the eponymous dolly zoom that’s since become ubiquitous, Vertigo is a poignant thriller about the many ways a person can be haunted.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Sci-fi can be divided into two categories: 2001: A Space Odyssey and everything else. Stanley Kubrick’s sprawlingly ambitious odyssey remains the genre’s peak more than half a century later. Though there’s still no true consensus as to what the ending means, there is a consensus among nearly 500 filmmakers that 2001 is the greatest movie of all time.

The Godfather (1972)

Named the greatest movie ever made by Entertainment Weekly and the second-greatest American movie by the American Film Institute, The Godfather is also heavily favored by countless dads, uncles, and grandfathers across the world.

No amount of praise can convey the sheer power of Marlon Brando and Al Pacino’s performances or of Francis Ford Coppola’s direction, all of which have become measuring sticks for greatness that few have met and fewer, if any, have surpassed in the decades since.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

There’s a reason the Sight and Sound poll has been mentioned so many times: It’s considered the list of all lists, and the one that Roger Ebert himself called “by far the most respected of the countless polls of great movies — the only one most serious movie people take seriously.”

And, in its 2022 edition, a surprising champion emerged: Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, whose mouthful of a title is matched by a nearly 3.5-hour runtime. Most scenes consist of little more than the title character, a widowed housewife played by Delphine Seyrig in an era-defining performance, completing household tasks in real time until finally erupting in a shocking act of violence.

It’s among the first feminist films as well as a “slow cinema” forerunner, and many would refer to it as a cult classic that’s finally begun to get its flowers on a larger scale. It’s a must-see for anyone willing to expand their conception of what a movie can do.