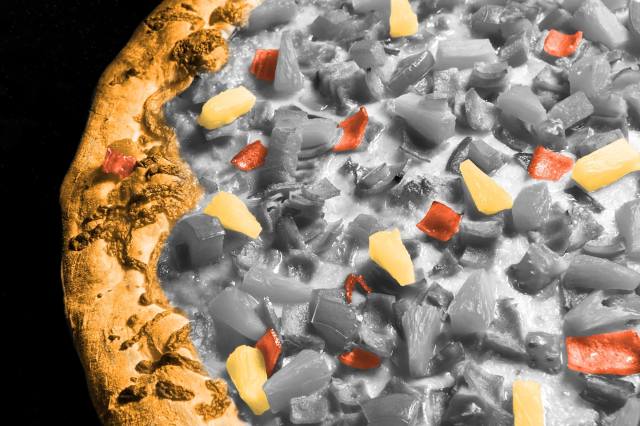

Hawaiian Pizza

While the war over pineapple as a pizza topping divides the world, the controversy originated nowhere near the Aloha State. Hawaiian pizza, the savory pie combining the salty umami of ham (or Canadian bacon) with the sweetness of pineapple, was the product of a Greek immigrant operating a restaurant in Ontario, Canada. Sam Panopoulos added Hawaiian-brand canned pineapple as a novelty topping in 1962, and the combination (along with the ’60s fascination with all things “tiki”) slowly gained popularity. In 1999, Hawaiian even became the most popular pizza style in Australia, accounting for 15% of sales.

Swedish Meatballs

Springy and savory, these meatballs are practically synonymous with Sweden — but everyone’s favorite IKEA offering is likely based on a dish from the Ottoman Empire. King Charles XII of Sweden was impressed by the entree while in exile in what is now Moldova during the early part of the 18th century. The meatballs, called kötbullar in Sweden, may be derived from the spiced lamb and beef recipe for köfte, a signature dish in Turkish cuisine. The Swedes substituted pork for lamb, and the dish is traditionally served with a silky sour cream-based gravy atop a bed of mashed potatoes or egg noodles and accompanied with tangy lingonberry jelly.

Baked Alaska

In 1867, the U.S. bought 375 million acres from Russia, land that would become Alaska. The purchase also inspired Delmonico’s chef Charles Ranhofer in New York to create a confection he dubbed “Alaska, Florida.” Spice cake was topped with a dome of banana ice cream — an expensive and exotic luxury at the time — then crowned with a layer of meringue toasted to a golden brown. A simplified version called “Alaska Bake” showed up in a Philadelphia recipe book in 1886, and within a few years “baked Alaska” was being offered on several menus around New York. Since then, baked Alaska has become a celebratory sweet, and the fancy dessert is a favorite for birthdays and other special occasions.

More Interesting Reads

Scotch Eggs

The pub food and picnic staple known as a Scotch egg is a popular snack across the U.K., but its origins may lie far from the British Isles. Along with curries and chutney, British soldiers returning from the occupation of India may have imported nargisi kofta — a dish of shelled hard-boiled eggs wrapped in spiced ground lamb, deep-fried, and served with an aromatic tomato sauce. Iconic department store Fortnum & Mason claims to have invented the British version in 1738, but the northern England county of Yorkshire maintains that the “Scotch” in the name came from eatery William J Scott & Sons, where the original version was wrapped in fish paste and the treats were nicknamed “Scotties.” Modern versions are usually coated in sausage and rolled in breadcrumbs before being deep-fried.

California Roll

Many Americans’ first introduction to sushi comes in the form of a California roll, but the approachable offering probably doesn’t come from Japan via the Golden State (although a couple of Los Angeles chefs do claim credit, and the origin is somewhat uncertain). Chef Hidekazu Tojo studied in Osaka before emigrating to Vancouver, B.C., in 1971. Noting that his new customers were intimidated by raw fish and seaweed, Tojo reversed the traditional roll process, encasing the unfamiliar ingredients inside a layer of rice. The “inside-out” rolls were popular with guests from California and also included avocado — popular in dishes from the state — which led to the name. At Tojo’s own restaurant, they’re simply known as “Tojo rolls.”