Early 20th Century

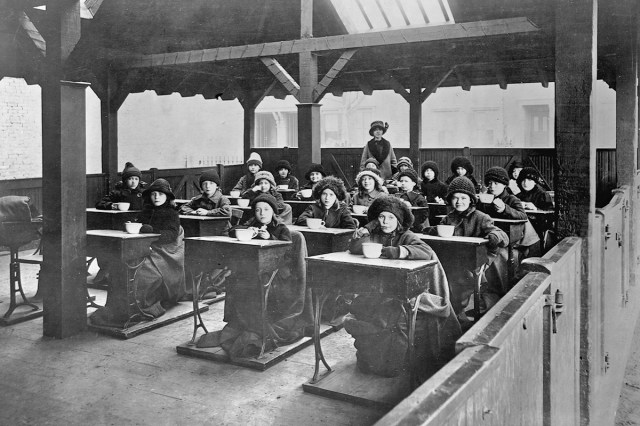

School lunches in the early 1900s were far from standardized — in fact, many schools in the U.S. didn’t serve lunch at all. After all, public education itself wasn’t compulsory in all 50 states until 1918. When school lunches were offered, they were often funded by charities, churches, local committees, or private donors, especially to assist low-income children.

While some students went home for lunch, economic hardship during World War I meant that many kids went home to little or no food. Around this time, pediatricians began emphasizing the benefits of receiving a well-balanced meal at school, which led to the emergence of school lunch programs across the country.

In 1910, one experimental program in Boston began to feed elementary students twice a week. Eating at their desks (the schools lacked cafeterias), students enjoyed sandwiches and milk prepared by home economics classes. In Milwaukee, some children were able to enjoy a warm meal by purchasing items such as soup and rolls for 1 cent. Those who couldn’t afford to pay received food for free.

Some schools received enough funding to provide students with a variety of lunch options, featuring à la carte pricing. In Cincinnati, for example, a rotating menu of five items was available for a penny each. The options included things such as hot meat sandwiches, sausages, baked sweet potatoes, oranges, bananas, “candy balls,” graham crackers, rice pudding, and cakes.

By contrast, rural districts across the nation didn’t receive the same level of funding as urban schools, leading to more meager lunch options. Students typically received cold meals, most of which were of “questionable nutritive value,” according to Gordon W. Gunderson, author of “The National School Lunch Program.”

Teachers took the initiative to help students heat jars of food brought from home by using water boiled in buckets on the classroom stove. Some foods commonly brought from home in these communities included soup, macaroni, and cocoa.

The Great Depression

As the Great Depression devastated the nation during the 1930s, growing concerns about childhood malnutrition pressured schools to respond accordingly. Many states introduced legislation allowing schools to serve daily meals, creating structure and uniformity among school lunch programs. By 1937, 15 states had passed laws authorizing schools to operate physical lunchrooms (which functioned like modern lunchrooms with staff and seating), and the federal government began offering support.

During this time, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) began purchasing surplus food from farmers and distributing it to schools and food pantries. Despite nationwide economic struggles, this federal intervention helped schools provide healthier meals, often including hard-to-get items such as fresh produce and meat.

Still, menu options were limited to what was available, so there wasn’t much variety. For instance, children reportedly hid apples in toilets to fake the appearance of having eaten them after growing tired of eating the fruit every day. A typical Depression-era school meal included a simple soup, such as lima bean and barley, with a bread-and-butter sandwich, chocolate pudding, and milk.

World War II

As the Great Depression came to an end, the U.S. found itself facing a new crisis: World War II. Schools began to place a greater emphasis on nutrition (known as “defense nutrition”) than ever before, to improve the readiness of future soldiers. During this era, recommended dietary allowances were introduced to establish a 2,000-calorie daily diet after many young military recruits showed signs of malnutrition.

A 1944 War Food Administration poster recommended a healthy school lunch should consist of one hot dish (e.g., meat or vegetables), a sandwich, fruit, and milk. Common menu items included chipped beef, broiled carrots, and prune pudding. For many children, this was the only hot meal they’d eat all day.

World War II highlighted the importance of school meals. After the war ended, President Harry Truman signed the 1946 National School Lunch Act, providing permanent federal aid for such programs and quickly expanding the availability of school lunches across the nation. In Truman’s words, “No nation is any healthier than its children or more prosperous than its farmers.”

More Interesting Reads

Baby Boom

Along with the postwar baby boom came a rising demand for school meals. During the 1950s, private companies began contracting with school districts to introduce more menu options. A focus on protein-rich meals — such as liver-sausage loaf, meatloaf, and pork-apple salad — started around this time.

The 1960s saw the emergence of modernized school cafeterias, featuring streamlined services, diverse menus, and a greater emphasis on taste. This was largely driven by the expanding student populations that followed the 1954 abolition of segregated schools.

School meals also became less health-focused, often featuring popular items such as country-fried steak, carrot relish, cornmeal yeast rolls, and peanut butter cake. However, schools didn’t receive enough federal money to cover their costs. During the 1970s, a series of legislation overhauled the lunch programs, allowing more districts to partner with private food vendors while simultaneously expanding free or reduced lunch programs.

Concerns about childhood obesity also began to grow during the 1970s. Efforts were made to promote healthier meals, but after opening cafeterias to the private sector, the introduction of fast food undermined nutritional goals. Although they were offered healthier choices such as vegetable soup and fresh fruit, students began to favor less nutritious items such as hamburgers, pizza, chicken nuggets, tacos, Jell-O, and juice. This marked the emergence of processed, prepackaged school foods, a trend that continues today.

Modern School Lunches

During the 1990s, fast-food chains such as McDonald’s found their way into school cafeterias, sparking a wave of reform. Nutrition advocates pushed back against unhealthy lunches, instead championing fresh produce, whole grains, and low-fat dairy.

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) of 2010 introduced significant changes by revising nutritional guidelines, regulating school vending machines, and giving thousands more students access to free or reduced-fare lunches. School salad bars gained popularity, but processed food remained a standard, albeit in new whole-grain or reduced-sodium forms. Today, schools continue to juggle taste, nutrition, and budget as awareness of healthy eating grows.