Emily Dickinson Kept Up Lifelong Friendships

Emily Dickinson rarely left the grounds of her home after 1865, when she was in her mid-30s, for reasons that are unclear. But she was social. Scholars have about a thousand of her letters to at least a hundred friends and family members — which may only be a fraction of all the letters she wrote. She often enclosed a poem in her letters. In a 40-year friendship, she sent Susan Dickinson, her brother’s wife, more than 250 poems. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the author of an Atlantic Monthly article that encouraged young people to write, received about 100 of her poems.

Emily Dickinson Stopped Attending Church in Her 30s

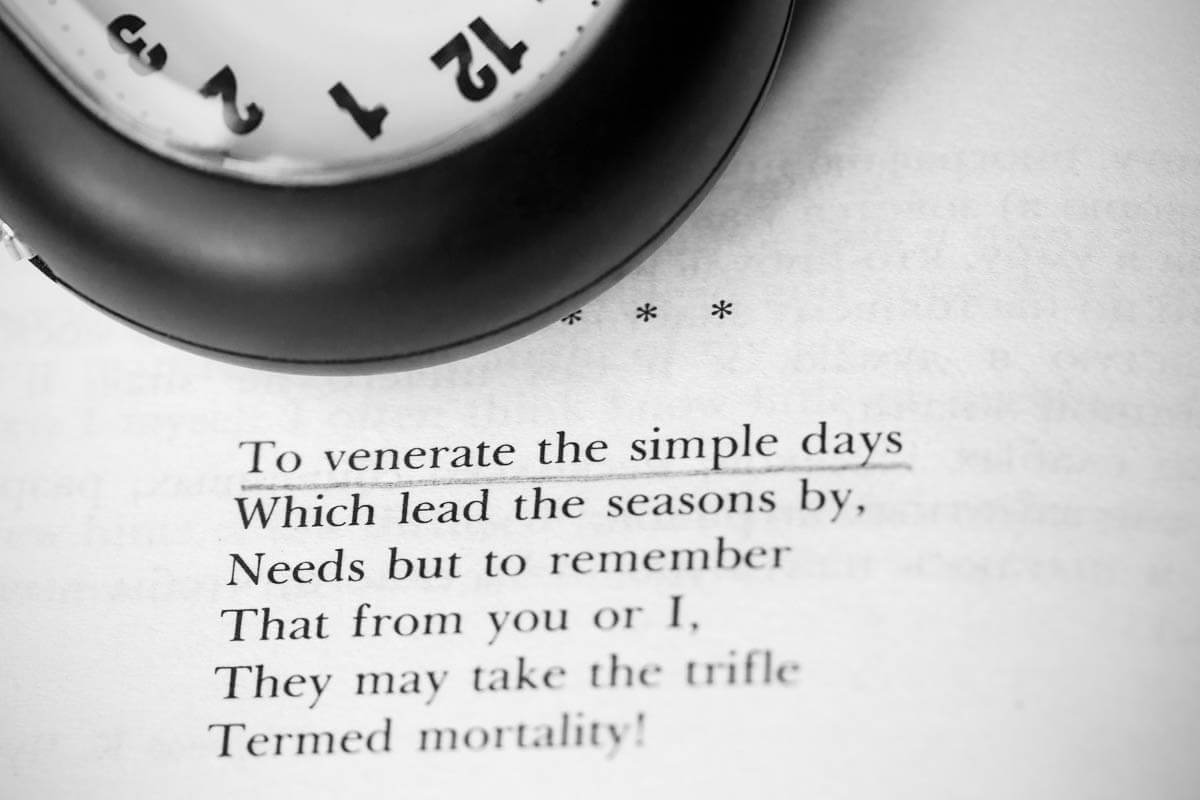

In her most famous poem, “I heard a Fly buzz–when I died–”, she takes on a question most of us wonder about at some point: What is it like when we die? In the poem, she imagines people at her bedside waiting for the “King” to “Be witnessed-in the Room.” Instead she hears a fly and then enters darkness.

Does this suggest a lack of faith? Again, it’s not clear. As a young girl, Emily attended services with her family every week, and participated in daily religious observances at home. Her mother was Calvinist, and in Emily’s teen years, several of her friends and her sister, father, and eventually her brother joined that Protestant movement. She resisted, saying to a friend, “I am one of the lingering bad ones.” By her late 30s, she had stopped attending services. However, her poetry continued to approach religious themes.

Her Father Was a U.S. Congressman

Dickinson was born into a prominent family. Her grandfather, one of the founders of Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts, overextended himself and lost the family’s land holdings. While most of the family left, her father, Edward Dickinson, stayed in Amherst and worked hard to reestablish the family’s standing. He succeeded, eventually entering politics and becoming a state representative and senator, then a U.S. representative.

As a child, Emily was afraid of him. She came to see him as “the oldest and the oddest sort of foreigner,” a lonely man, despite his longtime residence in Amherst. However, he was appreciated. After he collapsed while giving a speech in the state legislature on a hot June morning in 1874, and then passed away, the town of Amherst shut down for his funeral.

More Interesting Reads

She Composed Almost 1,800 Poems

Envelopes and scraps of paper suggest that Dickinson wrote notes spontaneously. Relatives say that she wrote at a table in her bedroom and at one in the dining room, where she could see the plants in her conservatory, and recited aloud in private. “I know that Emily Dickinson wrote most emphatic things in the pantry, so cool and quiet, while she skimmed the milk; because I sat on the footstool behind the door, in delight, as she read them,” her cousin Louisa wrote in her journal.

Among her papers discovered after Dickinson’s death were 40 handmade books that included more than 800 of her poems. All in all, she wrote close to 1,800 poems.

Only 10 of Her Poems Were Published in Her Lifetime

While Dickinson was alive, only 10 of her poems were published. Scholars believe that she did not authorize any of the publications, half of which appeared in the Springfield Daily Republican. (All were credited to “anonymous.”) The paper’s founder, Samuel Bowles, was a family friend, to whom Emily had sent about 40 of her poems.

Her White Dress Was Not Unusual

In her late 40s and early 50s, Dickinson wore a white cotton dress with mother-of-pearl buttons that was typical attire at home for women at the time. It could easily be cleaned with bleach. Did it mean anything to Emily that her dress was white? Her survivors chose to have her buried in white, within a white casket, when she died at age 55. It’s also true that the poet heroine of Aurora Leigh, a nine-book novel in verse by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, one of Emily’s favorites, wore white. But scholars don’t know if choosing that color had any particular significance for her.