The Full-Body Wag: Excitement

Few things evoke simple joy as much as a dog wagging its tail so fast and so broadly that its whole body wiggles. This type of enthusiastic wag — often paired with squinted eyes, relaxed posture, and a happy, open-mouthed expression — signals pure excitement. It’s a greeting many dog owners know from coming home after being away or when playing with their beloved pup.

Tail wagging isn’t something dogs are born able to do; puppies typically start wagging their tails sometime between 3 weeks and 7 weeks old. Wolves, dogs’ wild ancestors, rarely wag their tails, illustrating how domestication has played a role in shaping many communicative behaviors of tamed canines.

Slow and Low: Uncertainty

Not all tail wags are signs of happiness. When a dog wags its tail slowly, especially with the tail held lower than usual — half-mast or lower — it may be feeling uncertain or hesitant. This kind of wag is often seen in dogs who are assessing a new situation, perhaps encountering a stranger or sniffing out another dog or a new toy.

As with any type of tail wag, it’s important to pay attention to the overall body language. A hesitant tail wag, for instance, is often accompanied by a lowered head or a slightly tensed posture. Though you may be tempted to offer reassurance, it’s better to give dogs some space while they sort through those feelings of incertitude on their own.

High and Stiff: Alertness, Dominance, or Aggression

A tail held high with a firm, deliberate wag most likely isn’t a friendly gesture. In most cases, it signals alertness or dominance. According to canine behavior expert Stanley Coren, if the tail is held high while tightly wagging or vibrating, it may even signal an active threat.

This could indicate a dog is ready to fight or possibly run. If the tail suddenly stops wagging, it could mean the pup is attempting to avert a threat without becoming aggressive — but it could also signal it’s about to pounce. In interactions between dogs, a high, stiff wag can also be a way of asserting superior social rank.

More Interesting Reads

Wagging to the Right: Positive Emotions

Dogs don’t just wag their tails — they often wag them asymmetrically, and the specific angle can mean different things. Giorgio Vallortigara is a professor of neuroscience and animal cognition at Italy’s University of Trento who specializes in brain asymmetry and cognitive processing in animals.

In his work — which explores how animals process emotions and interpret spatial, numerical, and object-related information — he’s studied the directions of dogs’ wagging tails, and he believes the direction of a tail wag may be linked to brain hemisphere activity similar to right- or left-brain dominance in humans.

Brain lateralization was first recognized in human brains in the 19th century. In the ensuing years, research showed many animals experience similar lateralization, and Vallortigara’s research suggests dogs’ experience is much the same as humans. He and his team studied 30 pet dogs of various breeds, recording the dogs’ tail-wagging responses to different stimuli, and found dogs tend to wag their tails more vigorously to the right (from the dog’s perspective) when experiencing positive emotions, such as seeing their owner.

This, in humans — as, it appears, in dogs — is often a result of left-brain activity, which controls the right side of the body and is associated with feelings of calmness and approach-oriented behaviors including interaction, exploration, and engagement.

Wagging to the Left: Stress or Anxiety

Just as a right-leaning wag can signal positive emotions, a tail leaning more to the left can indicate stress or anxiety. Vallortigara and his colleagues found that when dogs saw something intimidating, such as an aggressive, unfamiliar dog, their tails wagged toward the left side of their body. This supports lateralization theory, as the brain’s right hemisphere controls the left side of the body and is associated with processing “withdrawal” feelings of fear, sadness, and heightened alertness.

Interestingly, Vallortigara’s team also found that dogs respond to the direction another dog’s tail is wagging, becoming more relaxed when they see a rightward wag and more anxious when they see a leftward one. Like Vallortigara’s findings regarding the link between certain stimuli and tail-wagging, other research has shown that stress in dogs can impact their behavioral lateralization, such as which paw they use more often.

Additional recent research conducted at the University of Trento and the U.K.’s University of Lincoln suggests that while dogs’ brain asymmetries can influence their emotions and behaviors, emotional lateralization is ultimately a complex concept shaped by multiple factors.

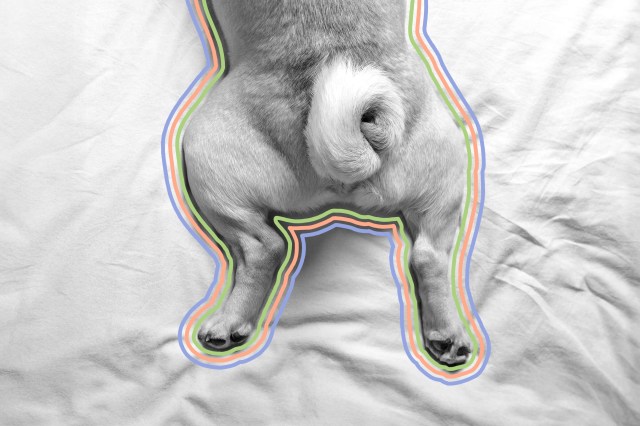

A Tucked-In Tail Wag: Submission or Nervousness

A wagging tail doesn’t always signal confidence, either. When a dog wags its tail while keeping it very low, it’s a sign of submission. If the dog goes so far as to tuck the tail between its legs, especially if a small, tentative wag persists, it indicates the dog is feeling overwhelmed.

This often happens when a dog is feeling fearful and trying to diffuse any potential conflict, which explains why we use the saying “with one’s tail between one’s legs” to express similar feelings of vulnerability in humans.