The Brain and Belly Are in Constant Conversation

The gut isn’t called the “second brain” for nothing. Trillions of microbes live in the digestive tract, breaking down food, producing vitamins K and B, and supporting nutrient absorption. They communicate with the brain through the gut-brain axis, a network of nerves (such as the vagus nerve) and chemical messengers, including serotonin and its receptors in the gut.

This bidirectional communication helps coordinate digestive activity, appetite, and even certain aspects of mood and behavior, which explains why your stomach may “flutter” when you’re nervous or why certain foods can affect how you feel. While the brain doesn’t control every gut movement, this system helps the digestive tract respond dynamically to both internal and external cues.

Stomachs Don’t Just Growl When You’re Hungry

Everyone has occasional hunger pangs, but to actually hear and feel your stomach growl is a whole other sensation. The same muscle contractions that move food through your gut while you’re digesting are also what cause that gurgling sound and feeling.

When your stomach is empty, your brain releases the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin. This tells the digestive muscles in the stomach and intestines to contract in waves, a process called peristalsis. Those contractions create the vibrations and rumblings you hear, made louder by the fact that the empty stomach means there’s nothing to muffle the sounds.

Contrary to popular belief, the noise doesn’t always signal feeding time; even a full stomach can growl as it churns and clears leftovers for the next meal. The rumbling sound — technically called borborygmi — comes from the Greek “borboryzein,” meaning “to rumble.” Unless it’s accompanied by unusual pain or bloating, borborygmi is a normal, healthy sign your digestion is working as it should.

Stomachs Can Hold as Much as a 2-Liter Soda Bottle

This probably won’t come as a surprise if you’ve ever felt your pants get a bit more snug after a big meal, but the stomach is remarkably elastic and can expand to hold a lot of food. This is because its inner surface, the mucosa, is lined with folds called rugae that unfold and stretch out to accommodate food as it arrives.

Adult stomachs start out folded up and roughly the size of a 16-ounce soda can. From there, the stomach can comfortably enlarge to hold about 1 to 2 liters of food and drink. If you picture that amount of sustenance as a 2-liter soda bottle, it sure doesn’t sound comfortable, but thankfully the stomach is able to slowly retract after digestion.

More Interesting Reads

We Swallow a Lot of Air

There isn’t much you can do to avoid swallowing air — every bite or sip brings tiny pockets of it into your digestive system as you eat. Overall, the average person swallows up to 2 quarts of air every day. Some small amounts can actually aid digestion, but habits such as eating quickly, chewing gum, or drinking carbonated beverages make for a greater volume of swallowed air. So where does it all go?

Most of the air makes its way to your stomach and leaves the body naturally through burping or flatulence. While most rumbles and bubbles are proof your gut’s digestive train is on track, too much air in the digestive system — called aerophagia — can cause bloating, discomfort, and excess gas.

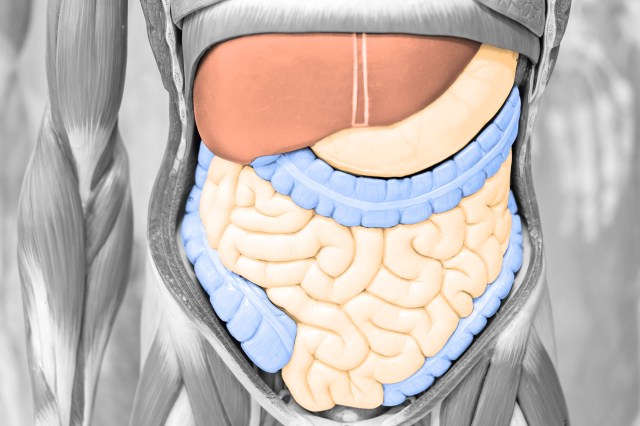

Intestines Are Impressively Long

The digestive system starts at the mouth and ends where waste exits the body, but the vast majority of it is made up of the intestines. The small intestine alone can be as long as 25 feet, and the large intestine adds approximately another 5 feet. Stretched out straight, that’s around the same length as an average school bus — just all coiled up and tucked out of sight inside your abdomen.

The small intestine does most of the work when it comes to breaking down food and absorbing nutrients, using its folds and tiny finger-like projections, called villi, to capture as much fuel for your body as possible.The large intestine then absorbs water and minerals while converting what’s left into solid waste. The intestines, particularly the small one, are workhorses, constantly moving food along, mixing it with digestive juices, and making sure your body gets everything it needs from what you’ve consumed.

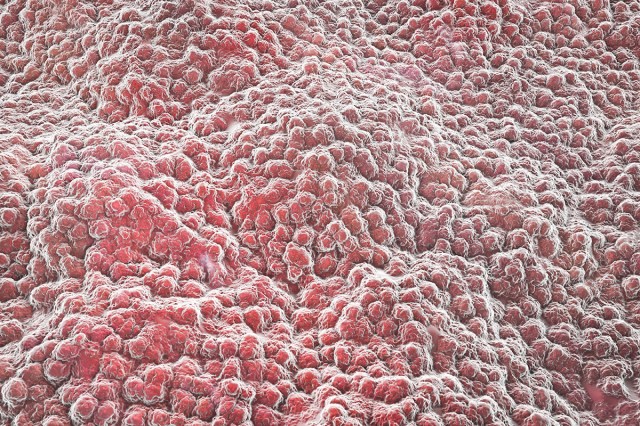

The Stomach Lining Is Always Renewing Itself

Digestive acids are powerful — so powerful that if your stomach didn’t protect itself, it could start dissolving its own tissue. To prevent this, the stomach lining, called the epithelium, is in a continuous state of renewal. And the turnover is pretty rapid: Cells regenerate every three to four days, ensuring the stomach can withstand the corrosive effects of the 3 to 4 liters of hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes it produces every day.

Even with the constant regeneration, the acids that break down proteins and aid nutrient absorption can be strong enough to start eroding the stomach tissue. Some factors can exacerbate this, such as excessive alcohol or pain reliever use, certain bacterial infections, and chronic stress.

We’re Not Born With the Healthy Bacteria Needed for Digestion

Babies enter the world free of worry and responsibility — and also free of a fully formed digestive system. Newborns are largely devoid of bacteria and other microbes essential for digestion and health. Their gut microbiomes first begin forming as they pick up bacteria in the birth canal, then continue to grow and diversify through exposure to breast milk, formula, and their environment. (Babies born by caesarean section get their first dose of bacteria in other ways, primarily from skin-to-skin contact and feeding.)

By the time a child is about 3 years old, the microbiome has become more diverse and stable, playing a key role in lifelong digestive health. This process highlights just how dependent humans are on our microbial communities: Digestion isn’t purely mechanical, but rather a cooperative effort between your body and the trillions of tiny organisms that call your gut home.