Cleopatra Isn’t Egyptian

Although she ruled Egypt as pharaoh from 51 BCE to 30 BCE, Cleopatra wasn’t of Egyptian descent. She was instead Greek, specifically Macedonian. Cleopatra was the last of a line of rulers of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, a dynasty founded by her distant ancestor Ptolemy I Soter. While the kings of this dynasty often fashioned their names after its originator, Ptolemaic queens preferred names such as Arsinoë, Berenice, and of course, Cleopatra (hence the “VII”).

Although Cleopatra wasn’t ethnically Egyptian, she does hold the honorable distinction of being the only Ptolemaic ruler who could actually speak the Egyptian language — along with half a dozen or so other languages.

Cleopatra Was a Popular Ruler

Historians have had difficulty accessing the legacy of a woman who, while singularly powerful during the ascent of the Roman Empire, has no surviving written words and scant contemporary accounts. From what experts and biographers can piece together, however, she was popular among the Egyptian people. Her fluency in Egyptian certainly helped, and she used her patriotism to earn her people’s affection. Cleopatra was known to commission portraits of herself in the classic Egyptian (or pharaonic) style, and in one surviving papyrus, dated 35 BCE, she is referred to as Philopatris, or “she who loves her country.” Plus, she garnered respect with her achievements: She reformed the monetary system, traded with Eastern nations including Arabia (which made Egypt wealthy), and also allied with Roman factions to prevent Egypt from becoming a de facto possession of an expanding empire.

Cleopatra Was a Victim of Roman Propaganda

Cleopatra’s legacy is so complicated because it tangles with historical biases against strong, female rulers and the propaganda of the early Roman Empire. Today, most people know Cleopatra as a seductress, one who had romances with two of the most powerful Roman leaders in the first century BCE, and who used her sex appeal to manipulate geopolitics in her favor. However, the source of many of these colorful tales is Octavian’s (later Caesar Augustus’) propaganda machine; he launched the equivalent of a fake news campaign to discredit the foreign queen and his rival Mark Antony. When Octavian proved victorious against Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, the victors became the authors of history, and it has taken millennia for scholars to learn more about the real life of this fascinating final pharaoh.

More Interesting Reads

Cleopatra Was in Rome When Julius Caesar Was Assassinated

Most of the drama during the infamous “Ides of March” in 44 BCE took place at the Theater of Pompey, where Julius Caesar — an emperor in all but name — was stabbed 23 times by Roman senators. But an untold side of the tale is that Cleopatra was in the city when Caesar was assassinated. Two years earlier, Caesar brought Cleopatra to Rome, along with their son Caesarion, and the foreign queen’s presence in the capital was a sensation, especially when Caesar erected a statue of her in the temple of Venus Genetrix. While some Romans were suspicious of Cleopatra, she became a style icon for Roman women, many of whom adopted her pearl jewelry and hairdo. Although Cleopatra remained in Rome initially in an effort to solidify her son as Caesar’s legitimate heir, the swift arrival of Octavian complicated matters and she soon decamped for Egypt.

She Likely Didn’t Commit Suicide by Snake

The traditional story of Cleopatra’s demise is as follows: Upon seeing her inevitable end as Octavian approached Alexandria, Cleopatra purposefully let a venomous asp — likely the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) — bite her breast. Although this dramatic episode is undoubtedly history’s most famous suicide by snake, historians have a tough time squaring this made-for-Hollywood account with some biological realities.

For one thing, the cobra is said to have been smuggled inside a fig basket, but Egyptologists and snake experts say a much larger serpent would have been needed to kill Cleopatra (along with her two handmaidens). Cobra attacks are also “dry bites” 90% of the time, meaning they rarely deliver deadly venom. Some historians believe that Cleopatra probably died by poison instead, likely hemlock mixed with wolfsbane and opium.

1963’s “Cleopatra” Is One of the Most Expensive Hollywood Films of All Time

The life of Cleopatra (or rather Rome’s colorful version of it) has inspired works of art for centuries — not the least of which was William Shakespeare’s tragedy Antony and Cleopatra, written around 1606. However, the most grandiose retelling of Cleopatra’s life, and one that had a profound impact on her legacy, is the 1963 film Cleopatra. Starring Elizabeth Taylor in the titular role (and also continuing the “beautiful seductress” trope), the film was originally budgeted at $2 million, but costs ballooned to an unprecedented (at the time) $44 million — about $430 million today. Although it was the biggest hit in theaters that year, the outsized cost of the film still made it a financial disaster for Twentieth Century Fox. The film’s failure also put to the sword any other future historical epics on a similar scale.

Cleopatra Lived Chronologically Closer to Us Than to Construction of the Great Pyramids

The civilization of ancient Egypt lasted for about 3,000 years — and the great pyramids and Cleopatra were on opposite ends of the empire. Egypt’s first pharaoh, Menes, formed the first dynasty around 3100 BCE. The Tomb of Khufu, the largest of the three Great Pyramids of Giza, was built around 2500 BCE. The smaller ones were built within the next century. Cleopatra’s reign started in 51 BCE, putting around 2,400 years between the three pyramids and her — and fewer than 2,100 years between Cleopatra and us.

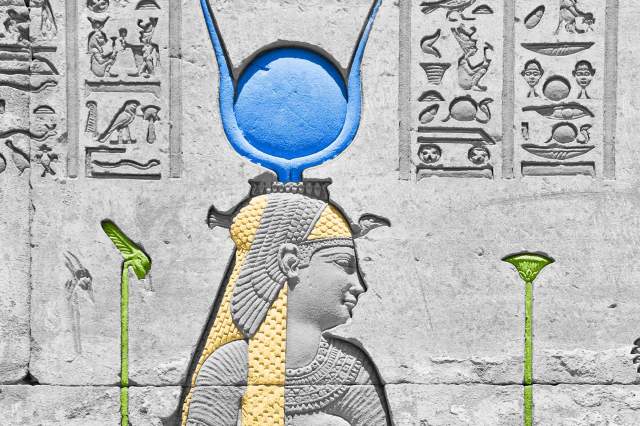

She Styled Herself After the Goddess Isis

In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were associated with the divine. Cleopatra identified with Isis, a major goddess whose wide-ranging powers dealt with magic, healing, and death. She wasn’t the first Cleopatra to gravitate toward Isis — Cleopatra III was also associated with her — so she was sometimes called “New Isis.” Mark Antony was associated with the Roman god Dionysus, and as the couple grew more public with their relationship, they ceremoniously stepped into the roles of the Egyptian pair Isis and Osiris and, in Rome, Dionysus and Venus.

She Married Her Brothers

It was very common for Ptolemaic royalty to in-marry — and while Cleopatra gained more notoriety for her romantic relationships outside the family, she did, at least ceremonially, marry two of her brothers. Many Ptolemaic people were born to brother-sister parents, but since Cleopatra didn’t have any known children with either of them, it’s possible the pairings were entirely political.

Upon taking the throne, she likely married her brother Ptolemy XIII, who was just 10 years old at the time, and ruled with him as co-regent. After Ptolemy XIII died in the Alexandrian War in 47 BCE (part of a power struggle between him and Cleopatra), Cleopatra married her brother Ptolemy XIV. He died just a few years later when he and his sister returned to Egypt from Rome following the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, and may have been killed on Cleopatra’s order to make room for her next co-ruler: her son.

She Ruled Alongside Her Toddler Son

Cleopatra’s third and final male co-ruler, at least officially, was Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as Caesarion, her son with Julius Caesar. Some writers during the era raised questions about the child’s paternity, but Caesar publicly claimed Caesarion as his own. The child was born in 47 BCE, just a few years before the death of his father and, with the death of his uncle-stepfather Ptolemy XIV in 44 BCE, he became co-ruler with his mother. At the time, he was only 2 or 3 years old.

Caesarion ruled, at least in name, well past babyhood, but after Caesar’s adopted son Octavian (later Caesar Augustus) defeated Mark Antony in 31 BCE, Caesarion was lured to Alexandria and executed in 30 BCE.

Her Full Name Translates to “Cleopatra the Father-Loving Goddess”

Cleopatra’s full name was Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator, which translates to “Cleopatra the Father-Loving Goddess.” Her co-ruling brothers Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV both had Theo Philopator, the masculine equivalent, in their titles. Their father, Ptolemy XII Theos Philopator Philadelphus Neos Dionysos Auletes, was the first of the Ptolemaic pharaohs to include “Theos,” or “God,” in his formal title, which continued with his ruling children.

Arab Scholars Had a Much Different View of Cleopatra

Westerners are more familiar with the story of Cleopatra that stemmed from Roman propaganda — but the Romans weren’t the only ones to tell her tale. Medieval Arabic writings paint her as a scientist who made major advances in mathematics, alchemy, and medicine, and even hosted academic seminars. They call her “the Virtuous Scholar,” and make little to no mention of her appearance. This version of Cleopatra could be just as exaggerated as the Western one, however — and some scholars think it’s likely these descriptions concern a different Cleopatra altogether, or perhaps stemmed from confusion caused by books that were dedicated to Cleopatra but written by others.