They Didn’t Call Themselves Aztecs

As with many ancient societies, much of what we know about the Aztecs comes from written accounts from outside their culture — in this case, descriptions from Spanish conquistadors who arrived in modern-day Mexico around 1519. However, the community that modern historians call “the Aztecs” actually referred to themselves as the Mexica or Tenochca people. Both names come from the region where the empire once flourished — southern and central Mexico, along with the capital city of Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City). The Aztec name likely comes from the Mexica origin story describing their homeland of Aztlan (the location of which remains unknown).

The Aztec Language Is Still Alive Today

At the height of the Aztec empire’s reign, Nahuatl was the primary language used throughout Mexico, and had been for centuries. Colonists arriving from Spain around the early 16th century introduced Spanish, which would eventually replace Nahuatl. But the Indigenous language isn’t at all dead; more than 1.5 million people speak Nahuatl in communities throughout Mexico, plus there are efforts in the southern U.S. to teach and revive the language. Spanish and English speakers who’ve never heard Nahuatl still know a few words with Aztec origins, such as tomato (“tomatl”), coyote (“coyōtl”), and chili (“chīlli”).

The Aztec Empire Had Vast Libraries

Surviving accounts from Spanish colonists describe the voluminous libraries of the Aztecs, filled with thousands of books on medicine, law, and religion. But early historians didn’t give the Aztecs enough credit when it came to written language skills, once considering the hieroglyphic style used by scribes as primitive. Few written documents have survived the centuries since the Aztec empire’s disappearance, most destroyed by Spanish conquistadors. But more recent evaluation of the last remaining texts shows that the Mexica people had a sophisticated writing system on par with Japanese that may have been the most advanced in the early Americas.

More Interesting Reads

The Mexica People Were Highly Educated

Aztec society had a rigid caste system dividing communities into four main classes: nobility, commoners, laborers, and enslaved people. Regardless of social standing, every child in the community attended school to receive specialized education, often for a role that was chosen at birth. Schools were divided by gender and social standing, though all Mexica children learned about religion, language, and acceptable social behavior. Children of nobility often received law, religion, and ethics training to prepare them for future leadership positions, and schools for commoners taught trade skills like sculpting, architecture, and medicine. Because Aztec culture centered on expansion and advancement through military strategy, teenage boys of all ages received military and combat training, while girls were educated in cooking, domestic tasks, and midwifery.

Aztecs Used Two Calendars

Mesoamerican calendars from societies of old have remained an interest to many people, especially those who speculate about astrological events or end of the world scenarios. But calendars used by the Aztecs weren’t too dissimilar from our own. The Mexica people relied on two simultaneous calendars: one 365-day solar calendar called the Xiuhpōhualli and a 260-day religious almanac called the Tōnalpōhualli. The solar calendar consisted of 18 months with 20 days, each month named for a significant festival or event. The religious calendar dictated auspicious times for weddings, crop plantings, and other events, using a 13-month calendar with each day represented by an animal or natural element instead of numerals.

Aztecs Wore the First Rubber-Soled Shoes

Centuries before rubber became an everyday mainstay in modern products, the ancient Mexica people were harvesting and collecting rubber tree sap for a variety of uses. Archaeological digs throughout Mesoamerica have excavated rubber balls likely used in ceremonial games or for religious offerings, but historians in the early 2000s found that Aztecs also created rubber soles for more comfortable and protective shoes. Researchers believe that Mexica artisans blended and heated rubber tree sap and extract from plants to create the rubber mixture, which could then be shaped and used for shoes, rubber bands, statues, and more.

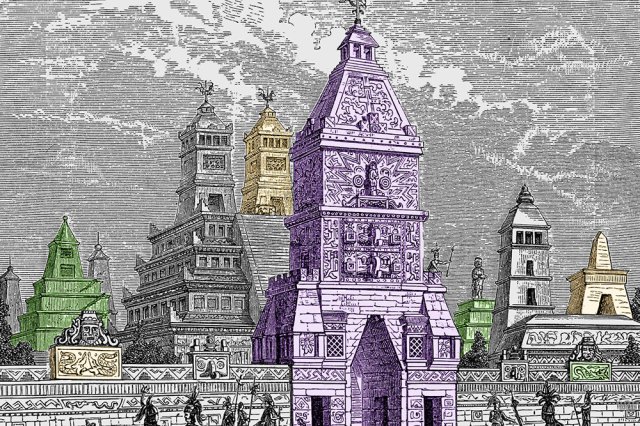

Farmers Created Floating Fields

Constructing the city of Tenochtitlan was no small feat for the early Aztec settlers, mostly because the city was built on water. While centered on an island within Lake Texcoco, the city expanded across the lake with bridges that reached its shores with aqueducts and canals that supplied Tenochtitlan with fresh water. Farmland wasn’t vastly available on an island of more than 400,000 people, leading Mexica farmers to create floating fields called chinampas. Gardens were constructed by weaving tree branches, reeds, and sticks between poles to create an anchored base covered with mud and dead plants that broke down into nutritious soil. Chinampas doubled as a sanitation system using human waste as fertilizer, which helped crops grow vigorously while protecting drinking water from contamination.