10 Fascinating Facts About “The Godfather”

Original photo by Allstar Picture Library Limited./ Alamy Stock Photo

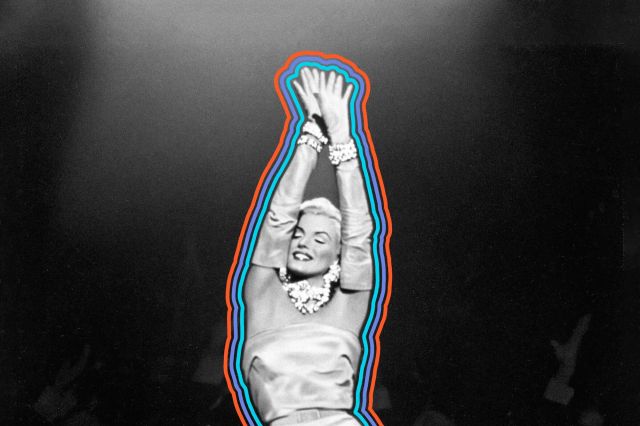

Revenge, guns, and cannolis — they all add up to an offer that audiences simply can’t refuse, turning The Godfather into one of the most beloved movie masterpieces of all time. Released on March 15, 1972, the two-hour-and-55-minute-long dark crime drama has found a permanent place in pop culture history with its quotable lines (“Revenge is a dish best served cold”) and memorable scenes (Michael’s retribution on Carlo) — not to mention winning three Oscars, including Best Picture, in 1973.

Already renowned for his work on Patton, writer-director Francis Ford Coppola cemented his name and legacy with the film, which also served as career-best turns for Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Diane Keaton, and James Caan. Here are 10 facts you may not know about the first film of the trilogy.

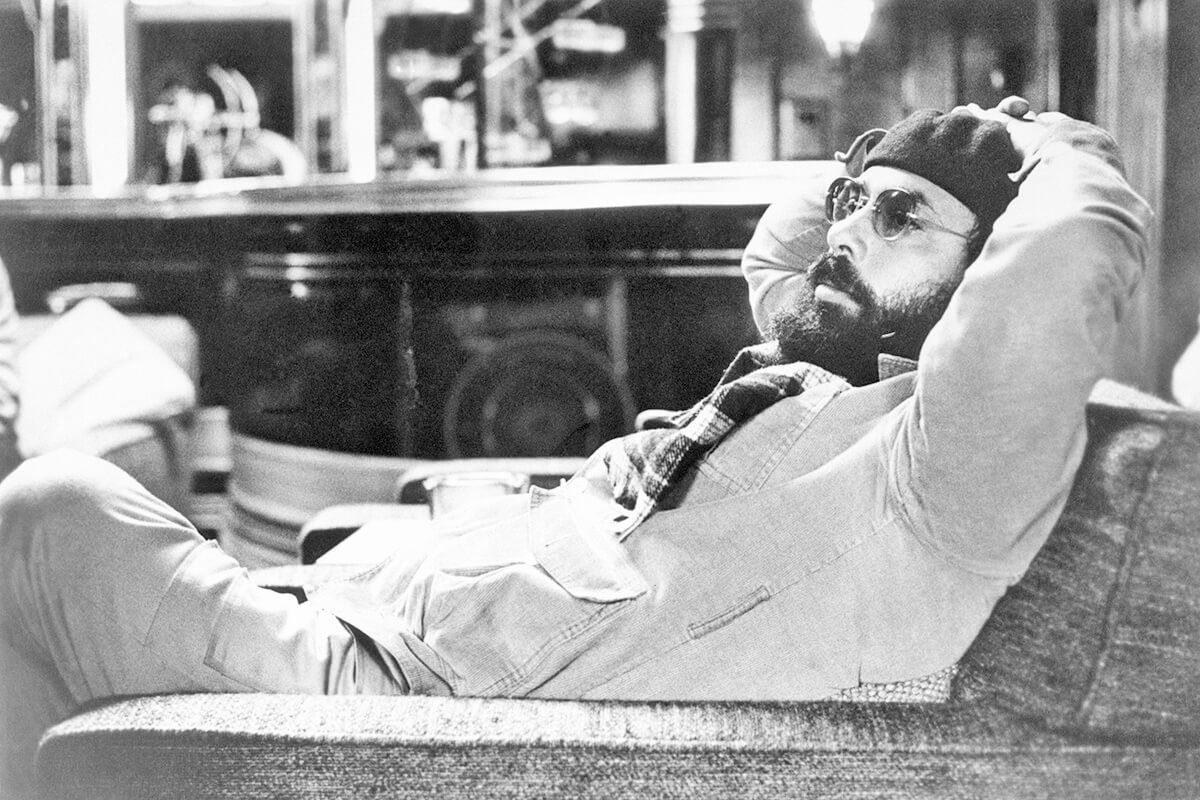

Coppola Wrote the Screenplay in a Tiny Cottage

The young writer toiled away at his screenplay far from the glitz of Hollywood in a one-room cottage in Mill Valley, California, about 15 miles north of San Francisco. “I was, like, about 29 when I started. I had two kids and one about to be born,” he told NPR. “I had absolutely no money.”

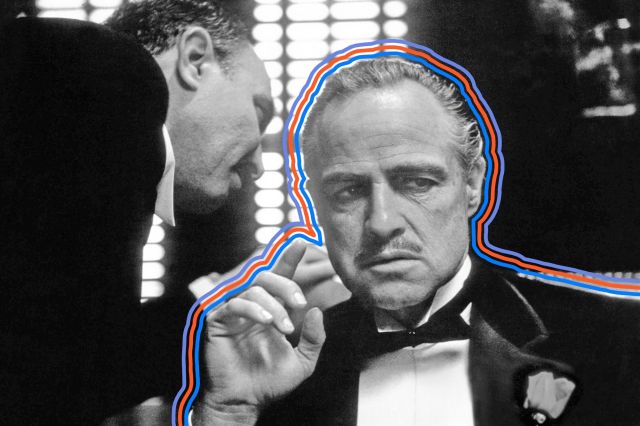

Several Actors Were Considered for the Role of Don Corleone

The Godfather book author Mario Puzo pushed hard for Brando to play the role of Don Corleone, especially after he heard that Danny Thomas, who was known for his comedy work, was up for the role. Other names in the mix were Ernest Borgnine (Marty), producer Carlo Ponti, and stage-and-screen legend Laurence Olivier.

Kansas City Was Considered as a Stand-In for New York City

Both St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, were scouted out as possible filming locations. “We were going to shoot in the really rotten part of Kansas City that does look a lot like old New York,” producer Al Ruddy said in The Godfather Legacy. “But we all wanted to shoot in New York from a very selfish standpoint.”

And Coppola went to bat for New York City. He told Kansas City radio station KCUR that the studio even sent him on a trip to scout out Italian neighborhoods in the city. “New York, in those days when we shot, had gotten a black eye of being a very tough and not good place to shoot — very expensive place to shoot,” he said, adding, “I was very adamant.”

The Cast Bonded Over Dinner at a Famed NYC Pizzeria

To get genuine interactions between the actors on screen, the cast started with a family dinner. “The first thing we did was to have a dinner up in Patsy’s restaurant around the table with Marlon sitting — when they all met him for the first time — sitting as the father and Al to his right and Jimmy to his left and Bobby Duvall,” Coppola told NPR. “My sister [actress Talia Shire, who played Connie] was serving the Italian food. And they just did an improv together as a family. And when that was over, they were a family.”

The Script Originally Started With the Wedding Scene

In an early draft, Coppola opened the film with shots of people arriving at the wedding. When he was about 15 pages into the script, screenwriter friend Bill Cannon came over and read it. “He says, ‘You know, Francis, you did such a good opening on Patton, that was such a striking opening for the Patton movie,’” Coppola told NPR. “‘Couldn’t you do something more like that, something more unusual that kind of got you into it?’ And I thought, well, there was some truth to that.” That’s when Coppola rewrote it to start with the closeup of undertaker Amerigo Bonasera.

The Old Man’s Dentures Fall Out When He’s Singing

While working on the latest restoration of the film, film archivist James Mockoski noted that the wedding scene has a bit more of a bite than may appear. “The old gentleman singing the song at the wedding, his dentures start falling out,” he said. “It’s fun to see things frame by frame, because you’ll see things that no one actually sees.”

The Cat That Don Corleone Strokes Was a Stray

While Don Corleone petting his cat in his office has turned into one of the more memorable moments, it was born out of spontaneity. Coppola noticed a gray stray cat roaming around the set, picked it up, and handed it to Brando to hold during the now-famous scene.

The “Take the Cannoli” Line Was Improvised

Both the book and script simply had the quote “Leave the gun,” from Clemenza (played by Richard Castellano). But the actor improvised and added “Take the cannoli,” based on a suggestion from his on- and off-screen wife, Ardell Sheridan, as a follow-up to a previous scene where she asked him to get the dessert.

There Was a Lot of Mooning on Set

In between takes, the mood was a lot more lighthearted, with Duvall and Caan often mooning Brando. But Brando did one better. He dropped his pants during the set-up for the wedding photo scene and mooned 500 extras on set. And just to cinch his status, Duvall and Cannon gave Brando a belt that said “Mighty Moon King.”

Coppola Didn’t Want to Make “The Godfather: Part II”

Despite being heralded as filmmaking royalty, Coppola said making The Godfather was a “tough experience” and had no desire to make another Godfather movie. “I was just glad I had survived the experience of The Godfather and I wanted nothing more to do with it. I didn’t even want to direct Godfather II,” he told The New York Times. It’s a good thing Coppola reconsidered — The Godfather II was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, won six, and became the first sequel to win Best Picture. AFI also ranked the 1974 film as one of the top 100 movies of all time.

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.