11 Things You Might Not Know About the “Peanuts” Comic Strip

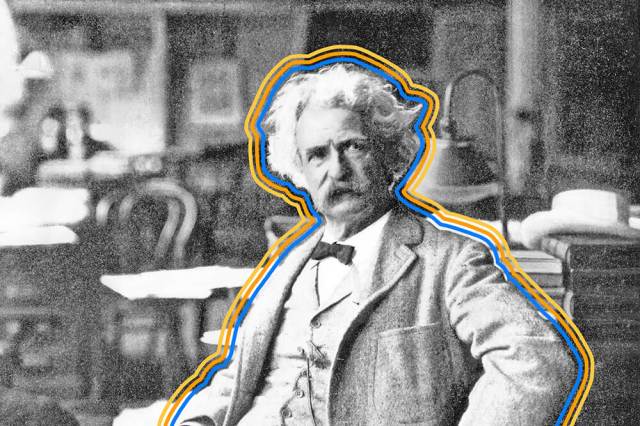

Original photo by Allstar Picture Library Limited./ Alamy Stock Photo

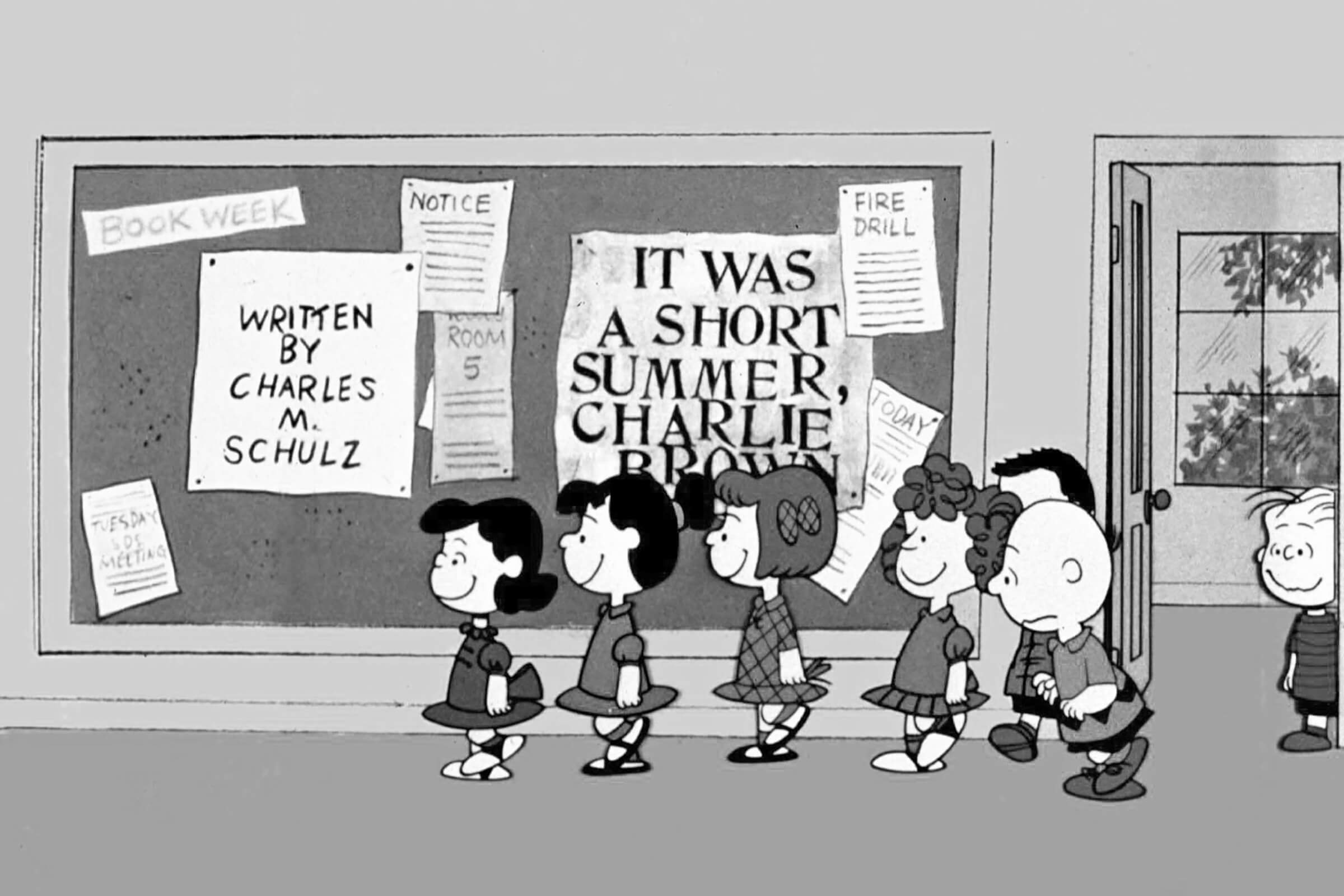

Charlie Brown and his gang of lovable young’uns are bonafide stars when it comes to classic American comic strip characters. Peanuts, the brainchild of cartoonist Charles Schulz, is so well-known that many of its quotes and common catchphrases are now a part of our cultural lexicon. (Think: “Good grief,” “AAUGH,” and “Happiness is a warm puppy.”) It has spawned numerous animated TV specials — 45, to be exact, including the 1965 holiday classic A Charlie Brown Christmas — and every Thanksgiving, a 50-foot-tall Snoopy balloon makes its way down Fifth Avenue as part of the annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Impressively, Peanuts has continued to run in syndication long past Schulz’s death in February 2000.

In short, the world that Schulz created half a century ago still resonates deeply with ardent fans of the comic and casual pop culture aficionados alike. At the time of Schulz’s death, he had produced 17,897 strips, and Peanuts had run in more than 2,600 newspapers worldwide and been translated into 21 languages. Still, even the comic strip’s most eagle-eyed fans might not realize just how groundbreaking it was for its time (it was the first major comic strip to introduce a minority character into its cast in 1968), or how far-reaching its pop culture impact has been (director Wes Anderson, for instance, has a Peanuts reference in nearly every one of his films). Here, we’ve rounded up 11 fun facts about Peanuts and its incredibly multifaceted legacy.

Charles Schulz Didn’t Pick — Or Initially Like — The Name for His Comic Strip

When Schulz first came up with the idea for a comic strip that revolved around a group of young neighborhood kids in 1947, he called the weekly panel cartoon Li’l Folks. At the time, he was illustrating the comic strip for his hometown newspaper, the St. Paul Pioneer Press. But when he brought the idea to the United Feature Syndicate in 1950, he was asked to change the name, given possible copyright issues with a different strip called Little Folks. Schulz suggested Charlie Brown or Good Ol’ Charlie Brown, but the syndicate decided on a different name entirely — Peanuts — after the children-only audience section of The Howdy Doody Show, which was referred to as the “Peanut Gallery.” (While Schulz may not have been aware, the phrase had racist origins in the 19th century.)

Schulz wasn’t exactly a fan of the new name — he thought it made the strip sound “insignificant.” He once said in an interview that he sometimes rebelled and submitted the comic without a title. Ultimately, though, Schulz and the syndicate reached a compromise: They would use the name Peanuts and run the subtitle Charlie Brown and His Gang on Sundays.

Snoopy Has Five Siblings

Snoopy, Charlie Brown’s beloved beagle (modeled after Schulz’s own pup, Spike), is one-of-a-kind. Over the years, he’s proved to be Charlie Brown’s best friend and confidante, an active dreamer, and an art aficionado, whose doghouse is supposedly adorned with works by Vincent Van Gogh and Andrew Wyeth. But Snoopy didn’t start out as an only pup.

Before Charlie Brown bought him from the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, Snoopy had five siblings, who have all made appearances through the years: Spike, who wears a hat, has a mustache, and lives in the desert outside Needles, California; Belle, Snoopy’s only sister who has an unnamed teenage son; Marbles, who is often referred to as the smart one in the family; Olaf, the misfit of the family; and Andy, who is always drawn with fuzzy fur and only appears in strips alongside Olaf.

Charlie Brown’s Dad Is a Barber, Like Schulz’s Dad

Although adults barely feature in the Peanuts world that Schulz created, Charlie Brown’s parents are two who are given the tiniest semblance of personalities in the comic strip. And by personalities, we mean job descriptions. Charlie Brown’s mother is a housewife (and one of the only characters who calls Charlie “Charlie”), while his father is a barber, just like Schulz’s dad in real life. Charlie Brown’s dad doesn’t actually appear in the strip, but he’s referenced often.

The Little Red-Haired Girl Was Never Given a Name, and Is Never Seen in the Comic Strip

Speaking of characters who never show their faces — Charlie Brown’s eternal crush, the Little Red-Haired Girl, is mentioned frequently but never actually appears in any of Schulz’s original comic strips (though she did make appearances in some later TV specials). The closest readers have ever come to seeing the Little Red-Haired Girl in print was in silhouette, in one of Schulz’s daily strips in 1998. She was never given a name.

According to a 2015 feature in The Week, there was a good reason for that: She was based on a real woman. Schulz dated the red-headed Donna Mae Johnson prior to Peanuts’ success; he even proposed, but she turned him down and married someone else shortly after. Schulz admittedly pined for her for years after, and in 1961 he created the mysterious Little Red-Haired Girl for Charlie Brown, possibly as a symbol of young, unrequited love.

Linus Didn’t Speak for the First Two Years of the Comic Strip

Many of Schulz’s characters represent a part of his personality, and Linus is no different. The oft-nervous younger brother of bossy (er, executive-potential) Lucy, Linus actually didn’t say his first word until 1954, two years after he was introduced into the comic strip. Schulz has referred to Linus as a manifestation of his “serious side … the house intellectual, bright, well-informed,” which may be why, he said, Linus has such “feelings of insecurity.” And while Linus’ trademark blue blanket didn’t exactly spark the term “security blanket,” it’s hard not to link the two in our cultural understanding of what a security blanket is these days.

A Trombone Was Used for Charlie Brown’s Teachers’ Voice

In the original comic strips, Charlie Brown and his friends are the focal point, while teachers and other adults are relegated to the backdrop. But when the popular comic was made into an animated series, producers knew they’d need to find some way to create a “voice” for adults in a way that still paid homage to Schulz’s wishes to leave adults out of the main picture. Composer Vince Guaraldi, who scored all of the early classics including A Charlie Brown Christmas and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, came up with the solution: Use a trombone with a mute in the bell to stand in for any adult dialogue. The result was what’s now widely referred to as the “wah-wah” voice.

“Peanuts” Was the First Major Comic Strip to Feature a Minority Character

Schulz was intentional about a lot of things when it came to how he framed his famous comic strip, but most especially when it came to race. The majority of the Peanuts gang had always been white, mostly because the cartoonist felt unsure as to whether it was his place to include minority characters in his story lines. But things changed in 1968 following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Schulz received a letter from a woman asking him to add an African American character to the comic, and three months later, in July 1968, Franklin made his comic strip debut, picking up and returning a beach ball that Charlie Brown had lost.

Critics have noted that Franklin is more nondescript than his white counterparts, but Schulz’s longtime friend and fellow cartoonist Robb Armstrong once said that he thought Schulz “played it smartly” with Franklin. “He was always very thoughtful in how he treated his characters,” Armstrong told NPR in 2018. And in fact, Schulz actually dedicated Franklin’s last name to Armstrong after the pair developed a friendship that lasted until Schulz’s death in 2000. Armstrong is the creator of JumpStart, one of the most widely syndicated Black comic strips ever.

Charles Schulz Once “Killed Off” a Character Because She Was So Unpopular With Readers

In November 1954, Schulz introduced a new female character to the Peanuts strip: Charlotte Braun, a loud, brash character who was meant to be the counterpart to bumbling, soft-spoken Charlie Brown (note the similarity between their names). It turned out, though, that readers weren’t ready for an opinionated female character and largely disliked Charlotte’s presence on the page. She made a total of 10 appearances in subsequent comic strips and then quietly disappeared without any explanation.

Some 45 years later, however, following Schulz’s death, a letter he had written to a disgruntled fan about Charlotte Braun was unearthed. In it, he wrote — perhaps jokingly, possibly not — that the reader and her friends “will have the death of an innocent child on your conscience. Are you prepared to accept such responsibility?” He ended the letter with a drawing of Charlotte with an axe in her head. The Library of Congress currently has the original letter.

The Final Peanuts Comic Ran the Day After Schulz Died

Schulz was a notoriously hard worker and was rumored to have taken only one real vacation in his career. (Reportedly, the only time Peanuts strips were ever republished during his lifetime were when United Features ordered him to take five weeks off around his 75th birthday.) It was perhaps fitting, then, that when he died of colon cancer two years later, it was just one day before his last original strip ran: Schulz never missed a deadline.

“Peanuts” Comic Strips Are No Longer Drawn

Unlike many other comic strips (such as Gasoline Alley, Blondie, and Beetle Bailey) which have brought on new artists to write or draw the cartoons after the original creator’s death or retirement, Peanuts ended with Schulz’s death in 2000. In December of the previous year, Schulz had announced that he would be ending Peanuts’ nearly 50-year run; his final daily strip ran in January 2000 and the final Sunday comic ran on February 13, 2000. Schulz used that strip as a farewell letter: “Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the schedule demanded by a daily comic strip. My family does not wish Peanuts to be continued by anyone else, therefore I am announcing my retirement. … Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy … how can I ever forget them …”

To this day, there have been no new strips released posthumously, and new animated specials must be based on story lines, themes, and dialogue that already exist within the strip’s 50-year history.

There’s a “Peanuts” Documentary That Never Aired

The very first Peanuts animation was made by Bill Melendez in 1959 for The Ford Show, a variety show sponsored by Ford Motors. Melendez would later form his own company, Bill Melendez Productions, and he was largely responsible for animating and directing all subsequent Peanuts television specials and movies — with one exception. In 1963, Lee Mendelson (who later produced nearly all of Melendez’s work) produced a documentary about the popular comic strip in collaboration with Schulz himself. The finished product, A Boy Named Charlie Brown (not to be confused with the above-mentioned Oscar nominee of the same name), never aired on TV. It is, however, available on DVD exclusively in the Schulz Museum Store.

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.