6 Rosy Facts About the Color Red

Original photo by Kontrec/ iStock

Red is the most complex color in the visible spectrum. In one moment, red can conjure images of war and bloodshed, and in another, transform into a symbol for passionate love and affection. Humans dedicated Earth’s red rocky neighbor to the Roman god of war, while the ruddy hues of roses show a deep devotion to someone we love. But the color red is even more important in the human psyche than you might realize, and these six facts show why this particular slice of the rainbow holds such a strong psychological sway over us.

Red Is at the Far End of the Visible Spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum contains a wide range of radiation, each defined by the size of its wavelength. On the extremely small wavelength end, there are gamma rays from supernovae, pulsars, and neutron stars, and on the other end of the spectrum, radio waves — perfect for communication, as the large waves easily travel through the atmosphere. Color is a small slice of electromagnetic radiation, and is known specifically as the “visible spectrum.” Within this spectrum, each color (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet) is also represented by a wavelength range. Violet, at around 380 nanometers, is the shortest wavelength. At 700 nanometers, red is the longest wavelength the human eye can perceive.

Just adjacent to this wavelength is infrared, a type of radiation we cannot perceive. However, just because we can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not important. Infrared is absolutely vital to humanity’s exploration of space, because the long wavelengths can pass more freely through cosmic dust. This allows astronomers using special telescopes to peer back billions of years into the very early beginnings of the universe.

Red Is the Most Common Color on National Flags

Purple is the least common color found on national flags (gracing only the banner of the Caribbean country Dominica), while red is the opposite, and can be found on a whopping 74% of flags, according to Guinness World Records. Around 50% of these flags use red to represent the blood of those who fought for the country, extolling the virtues of bravery and valor. This includes the U.S. flag, with the red standing for “hardiness and valor.” Meanwhile, when red is considered alongside vexillology’s second-favorite color, blue, only nine countries in the world (out of 196 total) have flags without red and/or blue in them.

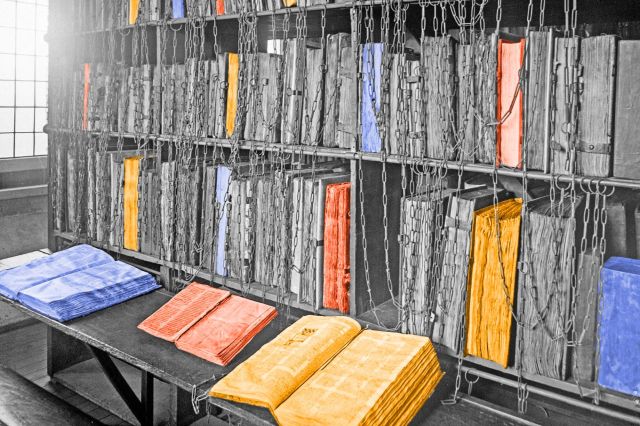

The Oldest Cave Painting in Europe Is a Red Dot

In 2012, scientists discovered that a painted red dot in a cave in northern Spain was likely the oldest cave painting found in Europe — it may be more than 40,000 years old. Red is one of the world’s oldest pigments, and is the primary color found in some of the world’s most famous cave paintings. That’s because our ancient ancestors discovered the long-lasting properties of natural clay known as ochre (pronounced OAK-er). Colored by hematite, a reddish material that contains oxidized iron, ochre withstands the ravages of time well. It can also be easily found in caves and valleys, which is why it is one of the primary mediums for humanity’s earliest works of art.

Finding the Color Red Attractive May Be a Part of Human Biology

Red means many things, and sometimes those meanings are contradictory — love and war, rage and lust, etc. Anthropologists concur that the color has been socially linked with lust dating back to humanity’s beginnings. Evidence suggests that red ochre was commonly used during fertility rituals in hunter-gatherer communities, often painted onto a woman’s body and face. Consider the Valentine’s Day obsession with red, and the throughline of sexualizing the color is obvious.

But some scientists think that there might be more to it than our own social conceptions. A 2008 study theorized that humans, much like closely related primates, subtly perceive the color red as a mating signal. While this is more obvious in primates such as baboons, who blush red as heightened estrogen levels increase blood flow near the skin, humans undergo a similar red-hued transformation, often becoming flush in the face or neck during sexual excitement. Some scientists have found a “romantic red hypothesis” in case studies determining attractiveness, with men and women both rating someone more attractive if they’re wearing red. However, other studies found negligible increases in attractiveness, or even a negative correlation, so the jury is still out as to whether humans are really hard-wired to be particularly turned on by red.

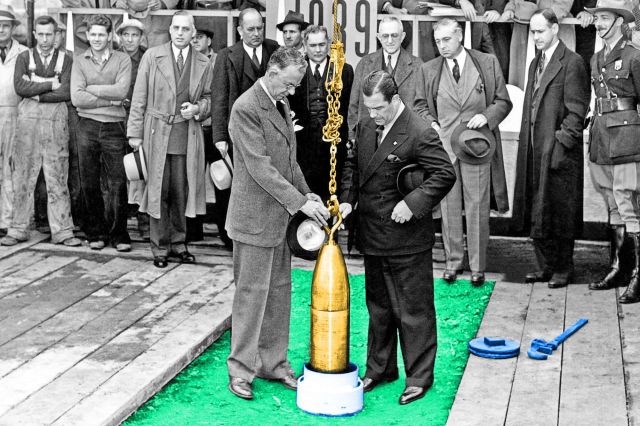

Iron Is Why Human Blood Is Red

Hemoglobin is a vital part of the human body, being the protein responsible for delivering oxygen to tissues, and for turning our blood red. That’s because hemoglobin contains a red-hued compound known as “heme,” with an iron atom that bonds with oxygen. Hemoglobin bound to oxygen absorbs blue-green light and thus reflects back bright red. This also explains why deoxygenated blood is a much darker red (“blue” veins are actually an optical illusion). Most mammals, fishes, reptiles, amphibians, and birds have red blood due to hemoglobin, but there are some exceptions found throughout the animal kingdom. For example, horseshoe crab blood, a vital ingredient for many vaccines, is actually blue because it contains hemocyanin, which uses a copper atom instead of iron for binding oxygen, and thus reflects light differently. Unlike our red blood cells, deoxygenated horseshoe crab blood is actually colorless rather than a deeper hue of blue.

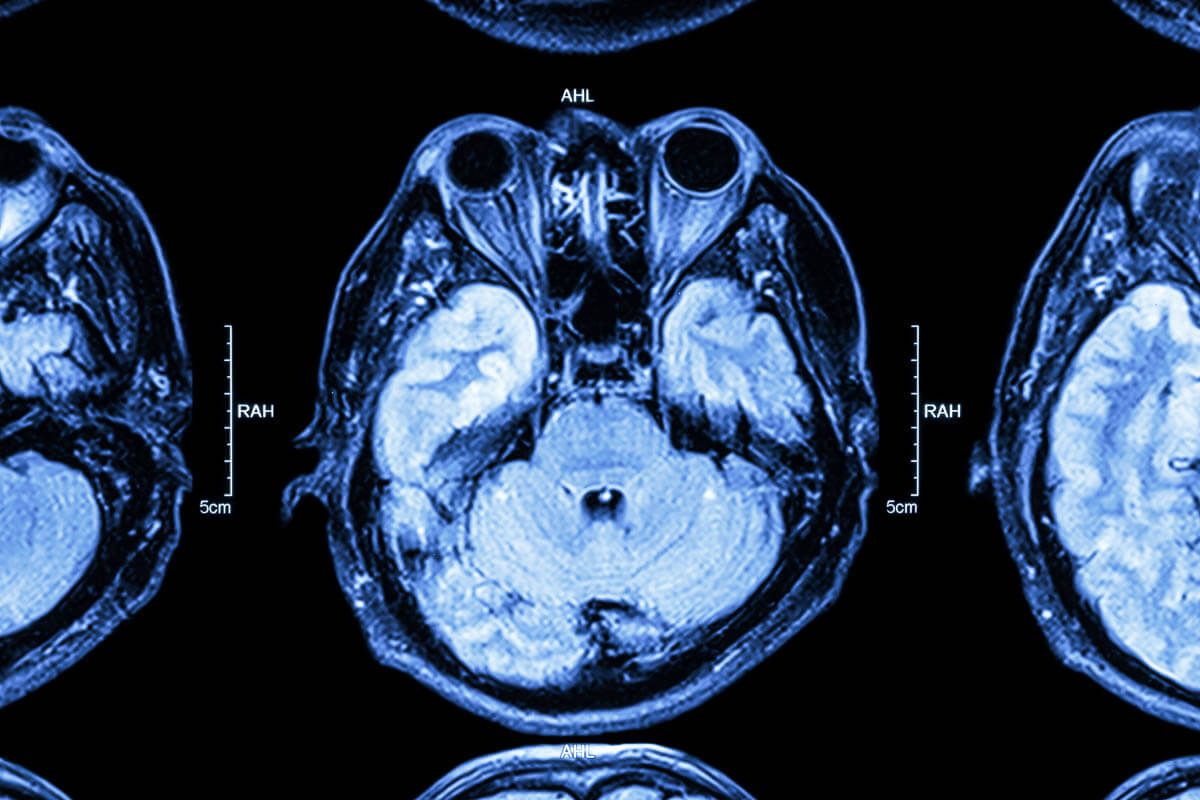

The First Color Humans Can Perceive Is Red

After only a few weeks of life, babies begin to distinguish their first color (after white and black) — red. Humans perceive color thanks to three types of cones found in our eyes, each tuned to short (blue), medium (green), and long (red) wavelengths. Although cones perceive color from birth, it takes time for the human brain to make sense of those inputs. Because an infant’s vision is blurry during the first few weeks of life, red is the only color capable of being captured by the retina when viewed around 12 inches from a baby’s face. At the two-month mark, babies can begin to distinguish between reds and greens, followed closely by yellows and blues a few weeks later.

Darren Orf lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes about all things science and climate. You can find his previous work at Popular Mechanics, Inverse, Gizmodo, and Paste, among others.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.