7 of History’s Most Significant Archaeological Discoveries

Original photo by LuFeeTheBear/ Shutterstock

Some of the world’s biggest archaeological discoveries not only changed the way we interpret our past but also solved historical mysteries. In addition to making front-page headlines around the world, many discoveries sparked cultural fads. Not every archaeological dig will yield a cache of priceless jewels or one-of-a-kind artifacts, but the finds mentioned below stand out as exceptional.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb

In November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron Lord Carnarvon located the tomb of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Unlike other royal tombs, Tut’s had remained virtually undisturbed for more than 3,000 years. Over the next few years, Carter unearthed an eye-popping collection of gold and ivory chests, statues of sacred beings, model boats, and other goods, plus Tut’s mummy and his iconic gold mask inlaid with semi-precious stones. The discovery of the best-preserved Egyptian tomb and its treasures set off a worldwide obsession with Egyptian-themed fashion, jewelry, and art.

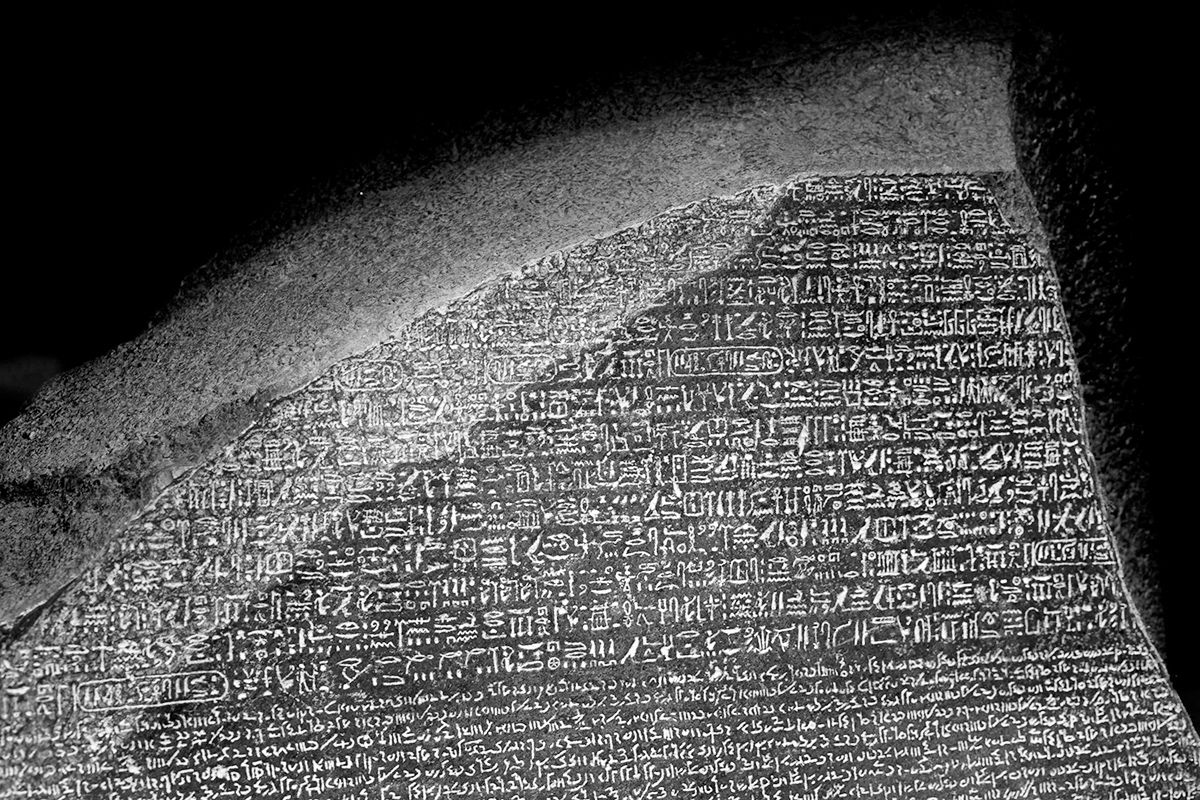

The Rosetta Stone

While digging the foundation for a new fort in July 1799, soldiers in Napoleon’s army found a fragment of stone in the Nile that bore the same message in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic script, and ancient Greek. By comparing the Greek text to the other two passages, scholars could finally decode the meaning of the hieroglyphics. Before the Rosetta Stone’s discovery, ancient Egyptian writing had been an undecipherable mystery. Later, scholars such as Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion showed that the hieroglyphics on the stone revealed names of important figures and other details of ancient Egyptian history. Reportedly, Champollion was so excited to have deciphered the mystery that he fainted.

The Skeleton of “Lucy”

In 1974, American anthropologist Donald Johanson and grad student Tom Gray stumbled upon “Lucy,” the skeleton of a single individual hominid (Australopithecus afarensis) who lived in present-day Ethiopia a little over 3 million years ago. Lucy proved to be a previously unknown human ancestor who walked upright — demonstrating that bipedalism evolved before larger brains — and was the most complete ancient hominid skeleton that had then ever been found. Since then, anthropologists have unearthed other hominid species with the help of modern technology, including Homo naledi in South Africa, Homo floriensis in Indonesia, and the Denisovans in Siberia.

Lascaux Cave Paintings

The fabulously detailed drawings on the walls of the Lascaux cave, which depict cattle, horses, bison, deer, and other animals, stunned the world when they were discovered by four young men in southwest France in 1940. Dating back about 20,000 years to the middle of the Late Stone Age, the drawings represent some of the earliest known figurative art and are a window into humankind’s cultural development. The Paleolithic painters may have used Lascaux as a ceremonial site or a place to demonstrate their artistic skills, but no one knows for sure.

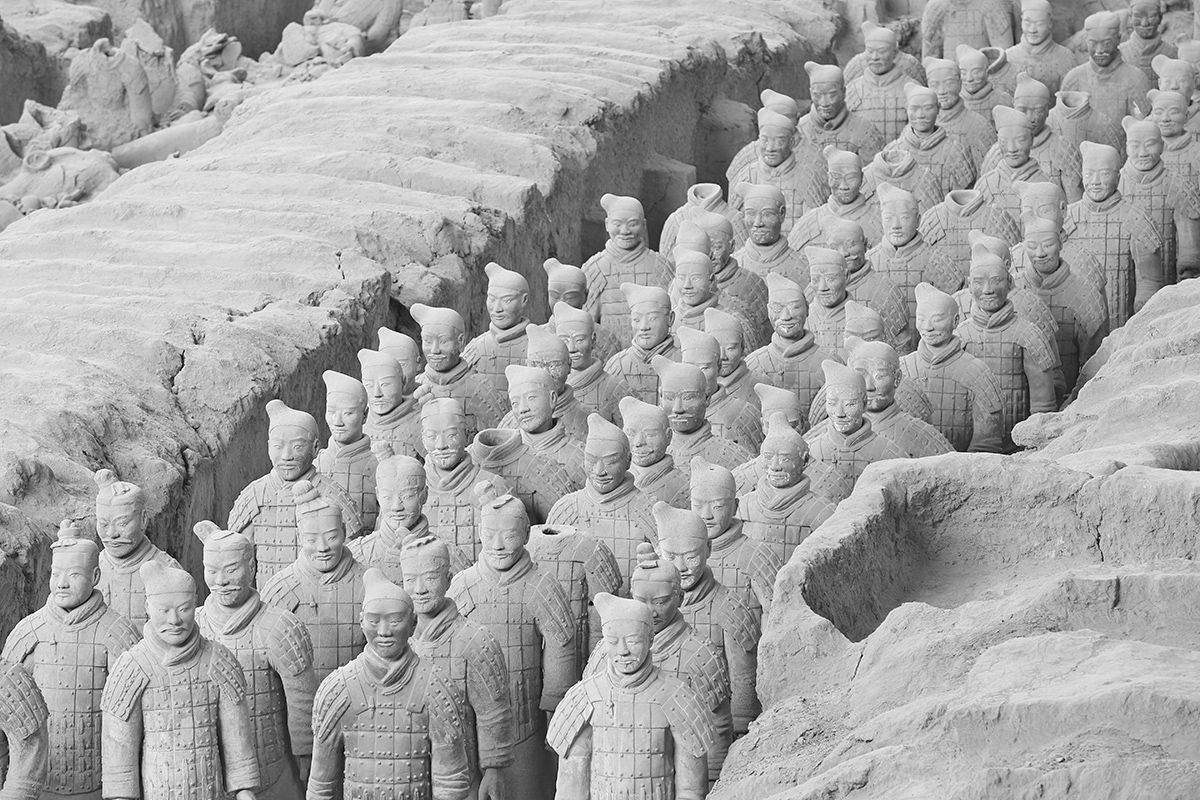

The Terracotta Army

In 1974, a farmer near the city of Xi’an, China, dug up some fragments of terracotta, which led to the discovery of thousands of life-size carved terracotta soldiers buried in the mausoleum of the first Chinese emperor, Qin Shi Huang, who had died in 210 BCE. Each warrior had a unique expression, and they stood four abreast in trenches as if ready to defend their leader. Carved horses, chariots, swords, and other weapons were also found. Much remains to be discovered at the mausoleum, which includes 600 burial and architectural sites spanning almost 22 square miles.

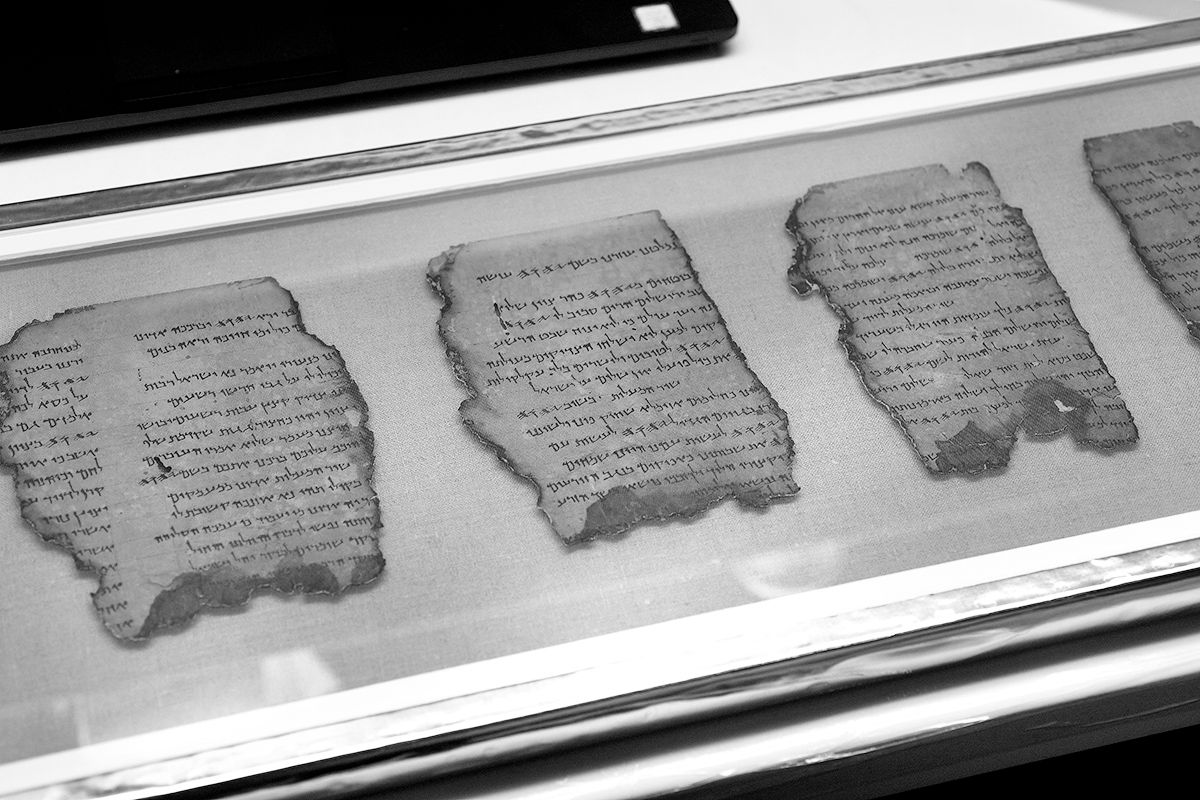

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of religious writings and books of the Hebrew Bible created between 2,000 and 2,300 years ago. Soon after the first seven scrolls were discovered in 1947 by a shepherd exploring a cave on the shore of the Dead Sea, the fragile manuscripts transformed historians’ views of Jewish religious life and culture two millennia ago. The texts revealed a Judean society influenced by different philosophies and practices, a world that gave rise to rabbinic Judaism and Christianity.

L’Anse Aux Meadows Viking Settlement

Thirteenth-century Icelandic sagas told of a group of Vikings, led by Leif Erikson, who sailed across the ocean to a lush new world. In the 1960s, archaeologists Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad discovered exactly where the Norse people landed around 1000 CE — modern-day Canada. The Ingstads located the ruins of European-style buildings at L’Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland, and further excavations revealed artifacts of Norse origin. The evidence confirmed the first European settlement in North America.

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.