8 Things You Didn’t Know About the Amazon Rainforest

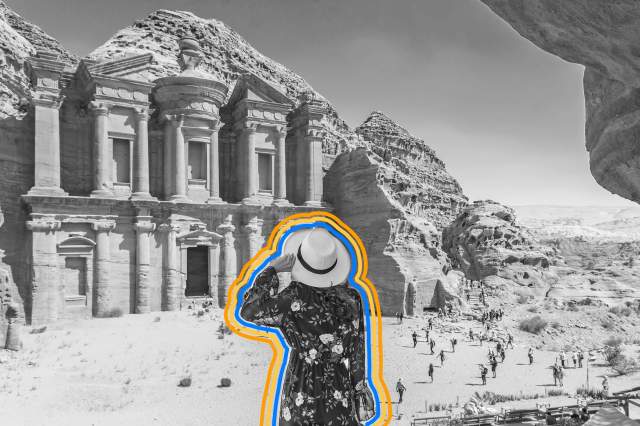

Original photo by USO/ iStock

The Amazon rainforest is the largest forest on the planet. Most famously associated with Brazil, it also extends across parts of Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guyana, French Guiana, and Suriname. The river of the same name that winds through it is the second-longest on earth — equivalent to the distance between New York and Rome. Most of us are at least vaguely familiar with this true natural wonder, but here are eight things you probably didn’t know about the Amazon rainforest.

While It’s the World’s Largest Rainforest, It’s Not the Oldest

The stats are impressive: Covering an area of approximately 2.1 million square miles, the Amazon rainforest is twice as big as Mexico. However, it falls short of the land area of the contiguous United States, which is nearly 3 million square miles by comparison. The Amazon also contains, by far, the world’s largest area of primary forest — dense areas of native tree species that are untouched by human activity — accounting for nearly 85% of its total size. The next largest primary forest is that of the Congo in Africa (about 650,000 square miles).

Although the Amazon is unquestionably the biggest forest on the planet, it’s nowhere near the oldest. Scientists estimate that the Amazon is approximately 55 million years old; the much smaller Daintree rainforest in Australia dates back 180 million years and is Earth’s oldest forest.

The Amazon’s Trees Aren’t Quite the Lungs of the Planet

French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted it and CNN reported it, but contrary to popular belief, the Amazon rainforest doesn’t actually produce 20% of the world’s oxygen. The late Wallace Broecker, an American geochemist and professor of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia University, debunked the popular myth as early as 1996. Since then, several other scientists have also disproved the statistic, including climate and environmental scientist Jonathan Foley.

It’s true that, each day, trees use the sun to photosynthesize large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, converting it into oxygen. However, ants, termites, bacteria, and fungi soon consume it. After the sun goes down, the trees also use some of that oxygen to enable them to continue to create energy. Considering all parts of the ecosystem, the end result is that trees produce, at best, a few percent, and certainly nowhere near 20% of the world’s oxygen.

The Amazon Rainforest Contains Unrivaled Biodiversity

The Amazon rainforest is one of the most biodiverse environments on the planet; according to Greenpeace, more than 3 million species live in it. (Unfortunately, due to deforestation, it’s estimated that one-third of them are threatened with extinction.)

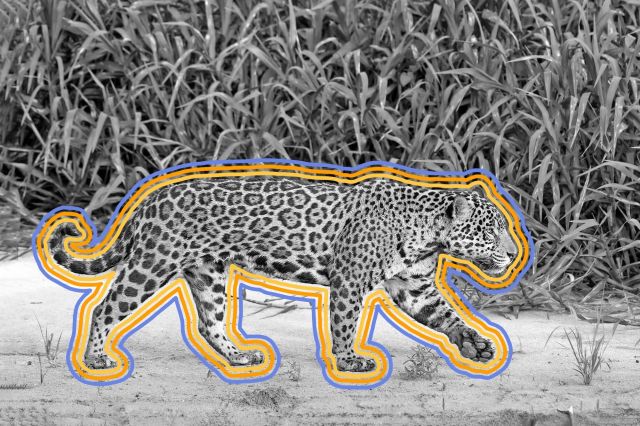

In the Amazon, you’ll find the jaguar, which is South America’s largest cat. This strong swimmer is happy munching on much of what hangs out in the same neighborhood, including deer, armadillos, monkeys, and lizards. A jaguar would be ill-advised to pick a fight with a black caiman, however: At over 16 feet long, this mighty crocodile is the Amazon’s biggest predator. Sharing the water is the green anaconda, the world’s heaviest and most powerful snake. Other notable creatures in the forest include the capybara, which looks much like an oversized guinea pig; the reclusive Amazonian tapir, with its squat trunk; and the three-toed sloth, one of the slowest-moving creatures in the world.

The Rate of Deforestation Is Alarming

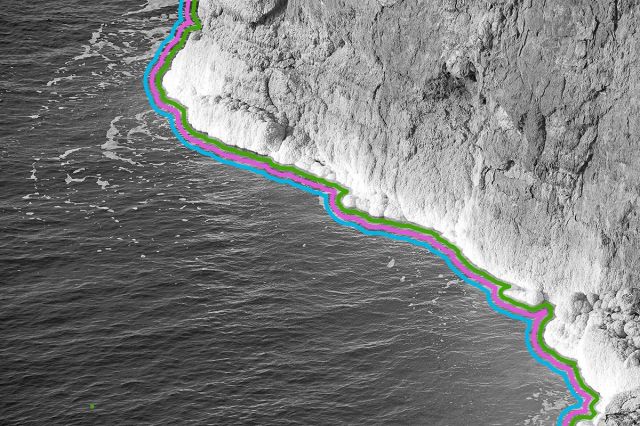

It’s difficult to determine the exact size of the area covered by the world’s rainforests, partly because much of it is inaccessible and because the rapid rate of deforestation makes it hard to maintain up-to-date figures. What scientists do know is that many millions of acres are burned every year. According to Conservation International, the Amazon lost about 3,600 square miles of rainforest in 2015, which equates to an area the size of Cyprus or the state of Maine.

Since then, the rate of deforestation in the Amazon has been on an upward trend. Land is being cleared for ranching, logging, and unsustainable agriculture. (Forest soils are poor because most of the nutrients are stored in the biomass. Once what’s in the soil has been used up, the leaf litter which once replenished the soil’s fertility is gone.) Companies also mine for gold and drill for oil in the area, and as communities demand new housing, infrastructure projects such as road building also contribute to the problem.

Its Plants Provide a Host of Health Benefits

Indigenous groups treat the rainforest as one big medicine cabinet. Approximately 80,000 plant species can be found in the forest, many of which have health-enhancing properties. Guaraná, for instance, contains four times as much caffeine as coffee. It was used in the Amazon as a tonic long before manufacturers of sports and energy drinks got wind of it. Equally well-known is the use of quinine, which is extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree and was traditionally used in the treatment of malaria. (These days, the World Health Organization recommends the use of other substances, which cause fewer side effects.)

Indigenous peoples also use matico leaves as a treatment for coughs, easing nausea, and as an antiseptic. The herbal supplement uña de gato, known in English as cat’s claw, is believed to help ease symptoms of rheumatism, toothache, and bruising. The bark and stems of the vine-like Chondrodendron tomentosum are a source of curare, which Indigenous hunters typically used as an arrow poison. Its muscle relaxant and paralysis-inducing properties have been studied to enhance our understanding of treatments for tetanus, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis.

More Than 400 Indigenous Tribes Call the Rainforest Home

Survival International suggests that around 1 million Indigenous peoples inhabit the Amazon rainforest. They form about 400 different tribes, each with their own language, culture, and identity. A few are nomadic, but most live in permanent settlements close to the river, which enables them to hunt, farm, fish, and access services such as health care and education. Some Indigenous groups — perhaps around 15 in Peru and at least twice that number in Brazil — are recognized as “uncontacted” and live an isolated life deep in the forest. However, recent reports indicate that some are choosing to make contact with the outside world.

It’s Home to the World’s Largest City Without a Road Connection

The Jesuits founded the Peruvian port of Iquitos in 1757, and the city’s population burgeoned as the rubber trade kicked in at the end of the 19th century. Today, the Iquitos’ urban area has almost half a million inhabitants. It is widely believed to be the largest city in the world without a road connection to the outside world. To reach it, most visitors catch a flight from Lima, though planes also touch down at two other regional hubs, Tarapoto and Pucallpa.

Essential supplies arrive by air, though most of what the city needs is brought in by cargo ship along the Amazon River. Small vessels shuttle between Iquitos and outlying settlements, while larger cruise ships carry tourists keen to experience the nature and wildlife that’s found in the remote rainforest.

There’s an Opera House in the Jungle

Across the border in Brazil, another city’s fortunes waxed and waned with the rubber industry. Manaus was already a thriving port city by the 19th century, thanks to its location at the confluence of the Rio Negro and the Solimões, which join to form the Amazon River. But as the increasing popularity of the bicycle, then the motor car, soon created an unprecedented demand for rubber, the city flourished. Its population grew rapidly as migrants flocked to the city to find work.

Those who had made their fortunes competed to build houses that would outshine those of their neighbors. The construction of the Manaus Opera House, which opened in 1897, was an example of the one-upmanship common at the end of the century — and a message to the rest of the world that this Amazonian city had arrived. Its success would be short-lived, however. As the industry collapsed, unable to compete with its Asian competitors, the theater was a casualty and closed in 1924. Fortunately, it reopened in the 1990s and now stages concerts and performances.

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.