15 Facts About Airports That Might Surprise You

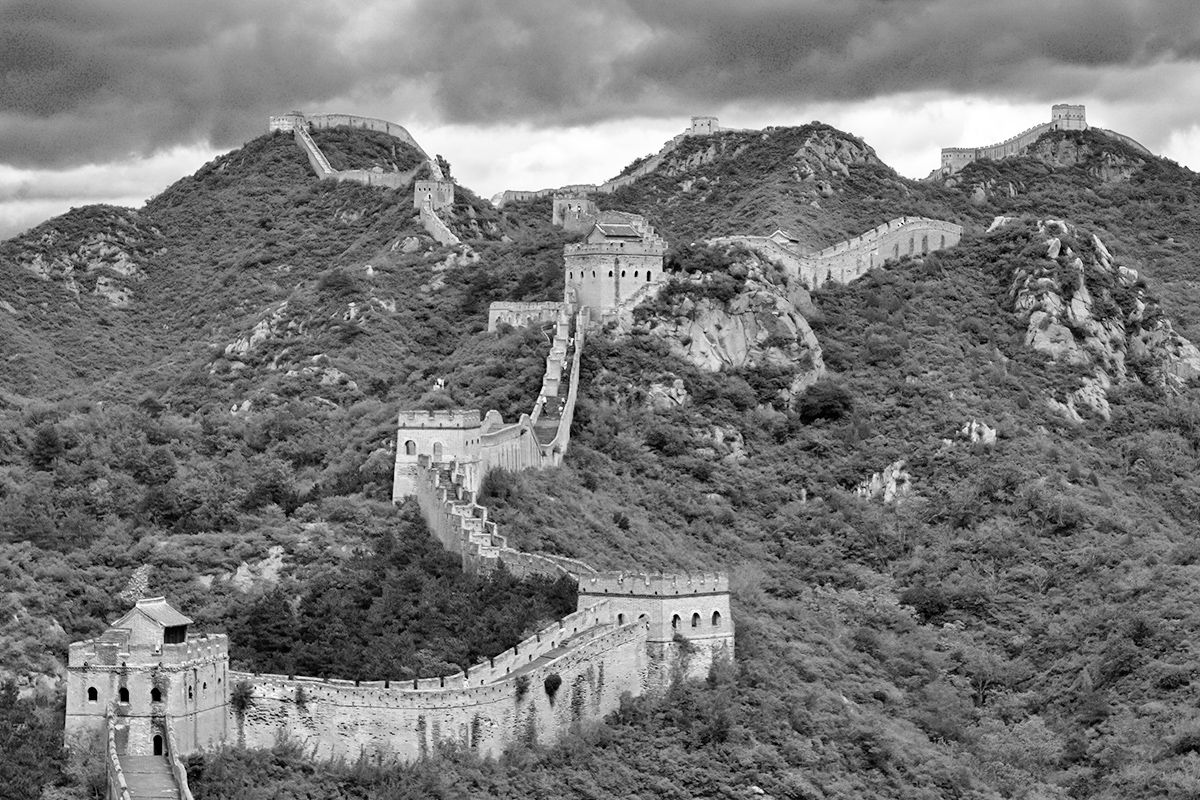

Original photo by Michael Rosebrock/ Alamy Stock Photo

What’s the world’s biggest airport? What about the busiest? Why is there an “X” in PDX? Is there a way to get a nap between flights? And what happens to all the change you leave in airport security bins?

Airports are big, crowded, and full of questions. The following 15 facts might change the way you catch your next flight — or at least end some mysteries.

The World’s Largest Airport Is the Size of New York City

King Fahd International Airport near Dammam, Saudi Arabia, has a larger area than any other airport. It’s 780 square kilometers, or about 300 square miles. That’s almost exactly the same size as New York City — yes, all five boroughs. As Guinness World Records points out, it’s larger than the entire neighboring country of Bahrain, which has three airports of its own.

ATL Is the World’s Busiest Airport

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Atlanta, Georgia, is the busiest airport in the world for passengers, serving 93,699,630 people in 2022 — and aside from a brief blip in 2020, it has held the No. 1 spot since 1998. It’s not even close: The next-busiest airport for passengers, Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, was more than 20 million people behind in 2022.

So why is it so popular? First, there aren’t a lot of other international airports in the immediate area, so it’s the closest international airport for much of the South. It’s also Delta Air Lines’ biggest hub. It makes a lot of sense for transfers, too. According to the airport, it’s within a two-hour flight of around 80% of the population of the United States — and unlike the major metropolitan areas that you’d maybe expect to be the busiest, it doesn’t have to deal with traffic from other nearby airports.

Celebs Pay Extra for Private Boarding

Celebrities do fly commercial, even if they’re flying first class, so why do you never see them sweating in the boarding line with everyone else? Many airports have private or exclusive terminals for the rich and/or famous. LAX (Los Angeles) and ATL (Atlanta) have The Private Suite, which provides comfy accommodations, valet parking, and, as the name suggests, private suites to hang out in while waiting for departure. It even has dedicated customs and security on-site. It’ll cost you, though: Memberships start at $1,250 a year, and that doesn’t even come with a discount for the $4,850 price tag on a preflight suite. It will get you free massages and manicures while you wait, though.

Airlines Pad Flight Times to Make Planes Look More Punctual

On paper, flights take a lot longer than they used to, even though the airports are located in the same place and the planes haven’t gotten slower. It’s because airlines have started building in some extra wiggle room, so that a plane has a better chance of landing at its destination on time, even if it has a delayed departure. Despite this, around 30% of planes still arrive more than 15 minutes after their scheduled arrival time.

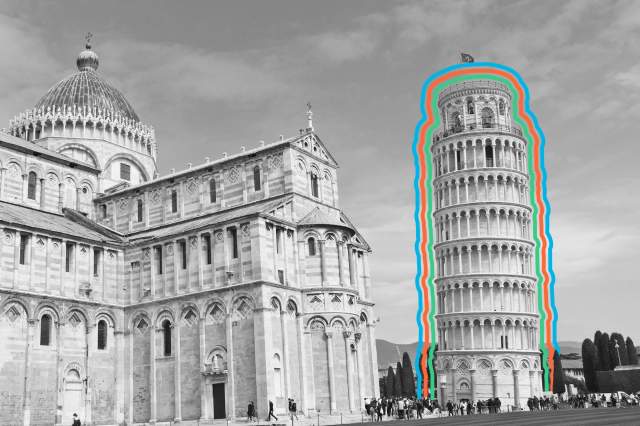

The World’s Tallest Air Traffic Control Tower Is in Saudi Arabia

Perhaps fittingly for the nation with the world’s largest airport (see above), the world’s tallest air traffic control tower is also located in Saudi Arabia. The tower at Jeddah King Abdulaziz International Airport in Saudi Arabia stands at 136 meters (446 feet), and surpassed the next-tallest tower, at Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia, in 2017. The tower in Saudi Arabia is about as tall as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Shortest Commercial Runway Is in the Caribbean

The Caribbean island of Saba, located in the Lesser Antilles, is only around 5 square miles, so there’s not a lot of room for an airport. (The island is also filled with rocky cliffs — it’s the tip of an underwater volcano.) They make do with only 900 feet of usable runway. For context, the typical commercial runway is between 8,000 and 13,000 feet long.

An Amsterdam Airport Has a Giant Park Inside

Amsterdam Airport Schiphol has all sorts of quirky, cozy amenities, including a library, an art gallery, and three-dimensional cow tiles, but Airport Park blows them all away. The green oasis opened in 2011, and while the vast majority of the plants are fake, it’s built around the very real trunk of a 130-year-old copper beech tree. To give the illusion of the outdoors, the airport pipes in parklike sounds such as birdsong. Visitors can even hop on a bike that also charges their phone. For a real breath of fresh air, there’s a small outdoor terrace.

In Airport Codes, “X” Is Just Filler

The “X” and the end of “PHX” makes sense for Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport — but what about “LAX” for Los Angeles and “PDX” for Portland?

Turns out, the “X” is left over from the days when airports used two-letter codes from the National Weather Service. With the rapid growth of air travel, it soon became apparent that two letters wouldn’t be enough. When International Air Transport Association (IATA) three-letter codes became the norm in the 1930s, some airports gained an “X” at the end.

Then there’s Sioux City Gateway Airport, which is blessed with the IATA code “SUX.” In 1988 and 2002, officials petitioned to change the code, and were offered five options by the FAA: GWU, GYO, GYT, SGV, and GAY. They opted to embrace what they already had instead, and introduced a line of merchandise — beanies, mugs, and more — emblazoned with the “SUX” logo.

The Wright Brothers’ Airport Is the World’s Oldest Continuously Operating Airport

Flight pioneer Wilbur Wright established College Park Airport in College Park, Maryland, in 1909 as a training ground for two military officers as they got ready to fly the government’s first airplane. More than a century later, it’s still a public airport, making it the oldest continuously operating airport in the world.

There’s a little bit of an asterisk on that record, though, in that you can’t really catch a flight there — unless you have or know somebody with an aircraft and a pilot’s license. Which brings us to…

Hamburg Airport Is the Oldest Continuously Operating Commercial Airport

If you’re looking for the oldest airport with terminals and plane tickets, look no further than Hamburg Airport, established in 1911. But while America was building its aviation history on airplanes, Germany built the facility around the country’s own technology: Zeppelins.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the inventor of the Zeppelin airship in the 1890s, gave an enthusiastic speech about the future of air travel in Hamburg in 1910. Residents believed in his vision, and the first building at the Hamburg Airport was an airship hangar, built in 1912. However, it took less than a decade for airplanes to start taking over. The airport broke the one-million passenger mark in 1961.

Airlines Pay Up to Eight Figures for Slots on the Airport’s Schedule

To keep air traffic running smoothly and safely in more than 200 of the world’s busiest airports, airport operators grant airlines slots that give them authorization to take off or land at certain times — and in many places, demand is far outpacing supply.

The most expensive slots are at Heathrow International Airport in London, England. In 2016, Kenya Airways sold its only slot to Oman Air for a whopping $75 million. That’s on the high side, but eight figures is relatively common. One year later, two slots fetched the same price when Scandinavian Airlines decided to sell.

Because an airline can lose that valuable asset if it doesn’t use it at least 80% of the time in a six-month period, you might see some unusual scheduling. At one point, British Mediterranean Airways was operating round-trip flights between Heathrow and Cardiff Airport in Rhoose, Wales — a journey of just a few hours by car or train — with zero passengers, angering environmental activists (among others). And with demand for air travel having decreased during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, some airlines aren’t canceling their underbooked flights, leading to more empty planes journeying through the skies.

Your Confiscated Items Might Be at Auction

Ever wonder where your favorite nail clippers and corkscrews went after airport security confiscated them? In some states, they end up in government auctions — and they sell in bulk.

Collections of forbidden goods, from 12 pounds of flashlights to 7 pounds of cigar cutters to an assortment of foldable shovels, end up on government-asset marketplace GovDeals.com. There are so many pocket knives that they get sorted into different categories before going on the market, ending up in lots of 100 generic-brand knives; 14 pounds of knives with names, dates, or locations on them; or 14 pounds of small-size Swiss Army Knives.

Lost luggage is also sold if it’s not picked up within three months, but the process is a little more streamlined. A reseller called Unclaimed Baggage sorts through and resells, repurposes, or recycles the bags and their contents. Speaking of airport security …

TSA Collects Your Loose Change

With hundreds of thousands of travelers throwing wallets into bins every day, some loose change is bound to fall out and get left behind. Over time, that really adds up; in 2020 alone, the Transit Security Administration (TSA) gathered more than $500,000 in loose change, and that’s during a pandemic — in 2019, they picked up more than $900,000. The biggest source of lost change was Harry Reid (formerly McCarran) International Airport near Las Vegas, where passengers left behind $37,611.61.

The TSA has to submit reports to Congress every year on how much they’ve gathered and what they spent it on. They ended 2020 with $1.5 million, including money leftover from previous years, and spent much of it on pandemic mitigation measures like masks, gloves, and face shields.

Airport Nap Hotels Exist

During a longer layover or delay, travelers sometimes stay at nearby hotels, then head back through security to catch their next flight. But if you just need a quick nap or a moment of quiet — or you’re worried about oversleeping — transit hotels are located literally inside the airport.

Aerotel has locations throughout Asia (and a few outside) for some sleep and a shower between, before, or after flights, whether you need an hour-long nap or an overnight stay. Yotel, with airport locations in Amsterdam, London, Istanbul, Paris, and Singapore, fills a similar niche: You can book as little as four hours in a relatively barebones room, with a bed or two, shower, and Wi-Fi.

More traditional hotels built for regular sleeping also exist inside airports, but often offer shorter-term options designed for decompressing during a layover — you just might pay a little extra for the bells and whistles. The Hilton Munich Airport offers a two-hour spa card, and Grand Hyatt DFW and JFK’s midcentury-themed TWA Hotel both offer fixed day-use rates that include access to the pool (starting at $109 in Dallas and around $149 at TWA).

Therapy Dogs Are An Increasingly Common Amenity

Anxious before your flight? Need a little dog cuddle? As of August 2021, dozens of airports in North America had some kind of therapy dog program, whether it was daily dog visitors or a once-a-month treat. One of the biggest operations is the Pets Unstressing Passengers (PUP) program in Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), which had around 121 dogs participating before the pandemic — most of them rescue dogs, and all of them with appropriate certifications and on-the-job experience. Each dog has a handsome red vest and weekly shift of 1-2 hours, and handlers double as customer service reps that can help you find your way to the correct gate.

Each therapy dog program is as special as its four-legged volunteers. Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL) in Broward County, Florida, has eight “FLL AmbassaDogs” that include a Yorkshire Terrier named Tiffany who rides around in a stroller. At the Edmonton International Airport in Alberta, Canada, pups and handlers wear matching outfits and distribute trading cards. In 2016, the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) added a Juliana pig named LiLou to its “Wag Brigade.”

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.