6 Amazing Facts About Juneteenth

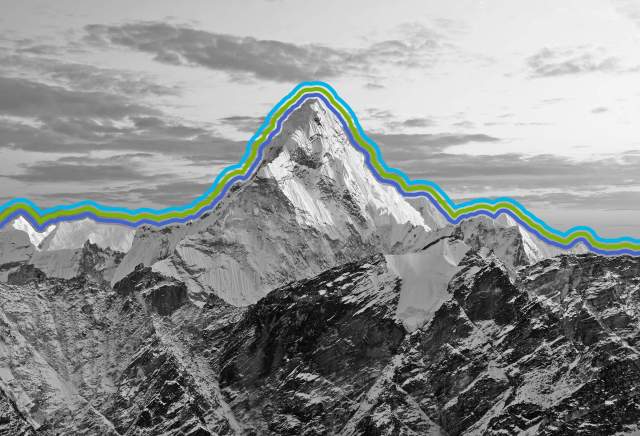

Original photo by Elena Dy/ iStock

On June 19, 1865, some 250,000 enslaved people in Texas gained their freedom, ending slavery in one of its last major outposts in the United States. Today, this momentous event is marked by a federal holiday known as Juneteenth, which is sometimes referred to as the U.S.’s second Independence Day. Although a new holiday for many Americans, Juneteenth has a long history. These six facts show why the day more than deserves a hallowed spot among the nation’s holidays.

Juneteenth Commemorates a Proclamation — But Not Lincoln’s

Most Americans are familiar with the Emancipation Proclamation — President Abraham Lincoln’s famous 1863 declaration that freed all enslaved people in the Confederacy — but the proclamation itself didn’t guarantee those freedoms. In fact, it would be a couple of years before Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House to General U.S. Grant. Although the surrender was the last nail in the Confederacy’s coffin, many Texas enslavers still resisted emancipation. On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger issued General Orders, No. 3, stating that “the people of Texas are informed, that in accordance with the proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” Backing up that order with 2,000 federal troops in Galveston, Granger ensured the freedom of a major portion of the last remaining enslaved people within the borders of the U.S.

The First Juneteenth Was Celebrated One Year After the Civil War

It didn’t take long for Juneteenth (originally known as “Emancipation Day” or “Jubilee Day”) to become a beloved celebration. One year after Granger’s General Orders, No. 3, the newly freed people of Texas celebrated the very first Juneteenth with community gatherings throughout the state that included sports, cookouts, dancing, prayers, and even fireworks. Over the years, celebrations became ever more elaborate — and more resilient, as racist Jim Crow laws took hold of the South. To continue celebrating the holiday, some freedmen even bought land in 1872 in Houston as a place to celebrate Juneteenth every year (today, that land is known as Emancipation Park; Juneteenth is still celebrated there). One by one, freed Texans traveled to other parts of the United States, and brought their Juneteenth customs with them. By the 1920s, the holiday was unofficially celebrated around the country.

The Color Red Is Prominent in Juneteenth Celebrations

For more than a century, Juneteenth celebrations have been accompanied by red velvet cake and red-hued refreshments, whether strawberry soda or red lemonade. There are a few theories behind this color-specific culinary tradition. One is that the color red is a significant hue in West African cultures, often symbolizing strength and spirituality. Another theory is that red featured prominently in the enslavement narratives of Yoruba and Kongo people forcibly brought to Texas in the 19th century. Other historians argue that the color is tied to special occasions dating back to ancient African traditions.

As for red drinks specifically, the tradition is likely linked to two West African plants — the kola nut and hibiscus — which can be used to make a variety of red-hued teas and refreshments. After the Civil War, newly freed Black folks also often infused lemonade with cherries or strawberries to make a cheap, refreshing drink. With the advent of food dyes and the arrival of the Texas-made Big Red soda in the 1930s, red foods and drinks were solidified as a staple of the Juneteenth menu.

Juneteenth Was Revived During the Civil Rights Movement

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the early 20th century, Black people living in Texas — along with the rest of the American South — were victimized by Jim Crow laws and a surging white supremacist movement. Many Black families left Texas during the Great Migration, and the holiday seemed doomed to be stamped out by this new wave of virulent racism. During World War I, some even viewed Juneteenth as unpatriotic, as it focused on a “dark chapter” of U.S. history. But the holiday found new life — nearly a century after it was first celebrated — during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s. The Poor People’s March on Washington, occurring only months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, was specifically organized to coincide with Juneteenth in 1968. By the 1970s, major cities around the U.S. were holding large Juneteenth celebrations, and in 1980 Texas became the first state to officially make Juneteenth a holiday.

Juneteenth Has Its Own Flag

Created in 1997, the Juneteenth flag is full of symbols — some more obvious than others. Starting with the most basic, the date June 19, 1865, running along the flag’s outer edge, represents the date of Granger’s General Orders, No. 3. The single star in the flag’s center represents Texas (aka “the Lone Star State”) as well as symbolizing the freedom of all Black Americans in all 50 states. Around the star is a “nova” (a kind of starburst), representing the birth of a new beginning for African Americans throughout the country, while the arc across the flag’s center represents a new horizon. Finally, the red, white, and blue color scheme tells us that enslaved people were and forever shall be remembered as Americans.

It’s the U.S.’s Newest Federal Holiday

Although the celebration of slavery’s end stretches back more than 150 years, Juneteenth didn’t become a federal holiday until 2021, when President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act. Prior to that, the last holiday to be recognized by the federal government was Martin Luther King Jr. Day, back in 1983. Before Juneteenth became a federal holiday, all but one state (South Dakota) recognized it as a holiday, though only six states — Texas, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, Washington, and Oregon — made it an official paid day off (that number has since grown). In 2023, more than 25,000 people will attend Philadelphia’s Juneteenth Parade & Festival, museums across Alexandria will organize Juneteenth events in Virginia, and citizens living in a free nation will return to Galveston, Texas, to once again celebrate the end of this great injustice.

Darren Orf lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes about all things science and climate. You can find his previous work at Popular Mechanics, Inverse, Gizmodo, and Paste, among others.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.