6 Fascinating Facts About the U.S. Flag

Original photo by Cirano83/ iStock

The history of the U.S. flag is almost as multifaceted as the people it represents. With dozens of different iterations, the Stars and Stripes has frequently changed as the country’s borders have expanded and new states have been added to the union. Today’s 50-star flag is hoisted at sporting events, schools, government buildings, and near the homes of millions of Americans throughout the world. These six facts pull together the threads of the flag’s 250-year history, including its creation, its symbolism, and where we’ll eventually have to squeeze that 51st star.

Betsy Ross Didn’t Design the Original U.S. Flag

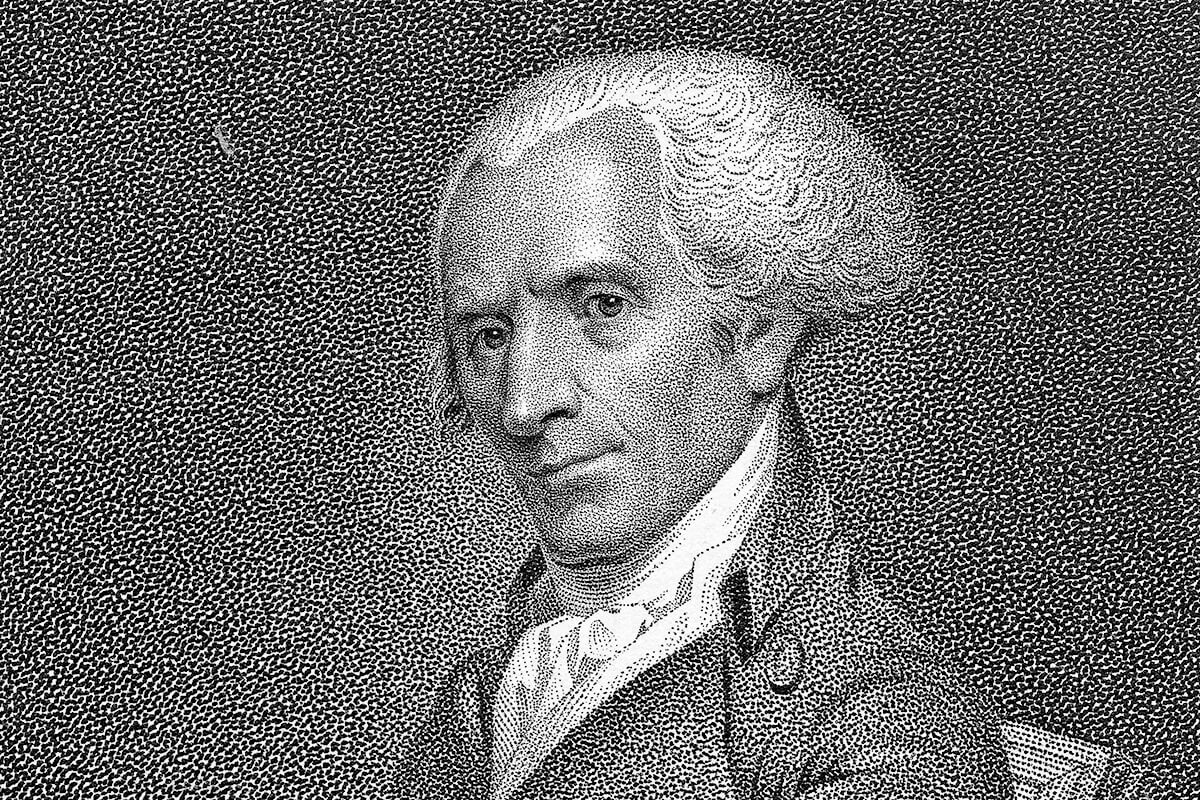

The most enduring myth about the origin of the U.S. flag is that Betsy Ross, an American upholsterer living in Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War, created the first flag at the behest of George Washington. Historians aren’t sure that ever happened, however. The source for Ross’ involvement came from her own family, nearly a century after Ross reportedly created the flag. Apart from her descendant’s account, no evidence suggests that Ross sewed the first flag. Instead, some historians think Francis Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and designer of other seals for U.S. government departments, is likely the first flag’s creator. Evidence exists that Hopkinson sought payment for the design of the “flag of the United States of America” (he thought a “Quarter Cask of the Public Wine” ought to do it). Although Hopkinson was denied payment, Congress approved his flag on June 14, 1777 (celebrated today as Flag Day). Thankfully, historians now generally give Hopkinson the vexillological accolades he deserves.

The First U.S. National Flag Featured the Union Jack

State militias fought the Revolutionary War’s opening skirmishes using colonial banners, but by the winter of 1775, the Second Continental Congress became the de facto war government of the fledgling U.S. — and they needed a flag to unite the cause. Congress went with something already on civilian and merchant ships, the British red ensign, and sewed on six horizontal stripes resembling the 13 red-and-white stripes on today’s flag. This creation became known as the Grand Union flag, and even featured the Union Jack (sans the St. Patrick’s cross) as a canton (the innermost square on the top left), instead of the usual constellation of white five-pointed stars.

The resulting flag was first hoisted on December 3, 1775, on the man-of-war Alfred, by none other than John Paul Jones, one of the greatest naval commanders in U.S. history. Years later, in 1779, the famous naval officer recalled the day: “I hoisted with my own hands the Flag of Freedom…”

There Are 27 Official Versions of the American Flag

Although the Grand Union Flag was the first banner to unite the colonies’ cause under one emblem, the flag isn’t regarded as an “official” U.S. flag. That lineage begins with the passage of the Flag Act of 1777, which states “[t]hat the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” The colors themselves represent valor (red), purity (white), and vigilance (blue). Some flags included different versions to appeal to this description, such as the so-called Betsy Ross flag, Hopkinson’s 3-2-3-2-3 star arrangement flag, and the Cowpens flag (basically the Betsy Ross, but with a star in the middle of the circle). Hopkinson’s creation is widely regarded as the first conception of what would be recognizable today as a U.S. flag.

Throughout the years, the flag has undergone 26 small changes in order to add new stars for new states joining the union. The first change came in 1795, with the addition of Vermont and Kentucky (which added two extra stripes as well), and this version is what’s known to history as the Star-Spangled Banner. The last canton edit came on August 21, 1959, when President Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10834, establishing today’s 50-star flag following Hawaii’s statehood.

The Original “Star-Spangled Banner” Still Exists

After a night of heavy bombardment during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812, American forces stationed at Fort McHenry raised the Star-Spangled Banner (the 15-star flag) on the morning of September 14, 1814. Seeing this flag while standing aboard a British ship and negotiating the release of a prisoner, author Francis Scott Key composed the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” which later became the lyrics for the U.S. national anthem (adopted by Congress in 1931).

The original flag was sewn by Mary Pickersgill and Grace Wisher, her enslaved servant, and stretched some 30 feet by 42 feet — an extremely large flag at the time. The gargantuan size of the Star-Spangled Banner was a specific request of Fort McHenry’s commander, George Armistead, who told the head of Baltimore’s defenses that “it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.”

Amazingly, the very flag that inspired the 35-year-old poet more than 200 years ago still exists, and is now in the care of the Smithsonian Institute — though sadly not quite in its original condition. For nearly a century, the flag remained in the care of Armistead’s descendants, who made a habit of cutting off pieces of the flag to give as souvenirs. Today, the Star-Spangled Banner is only 30 feet by 34 feet. Although the Smithsonian has recovered many of the lost pieces over the years, some prominent pieces — including a missing 15th star — have never been recovered.

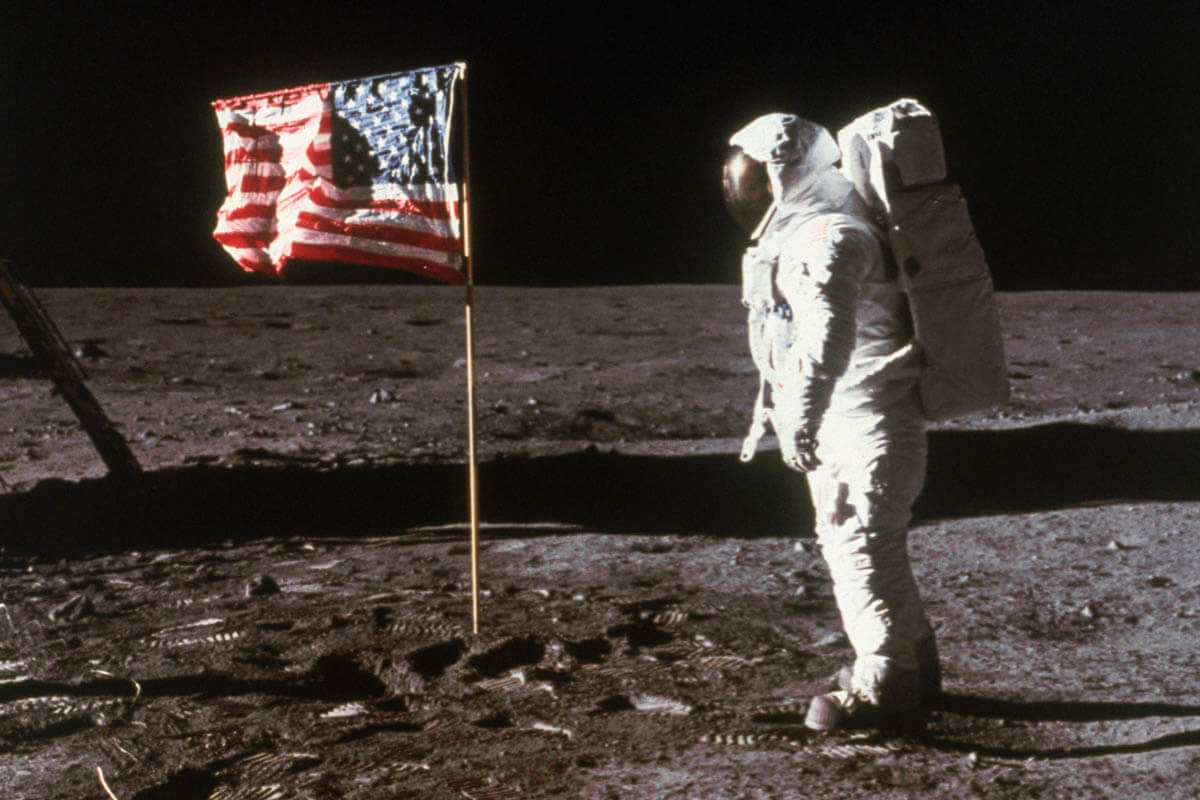

The U.S. Flags on the Moon Are Probably White Now

Today, the U.S. flag is one of the only banners that’s been hoisted somewhere other than planet Earth. Six of the NASA Apollo missions (1969 to 1972) planted a U.S. flag on the moon (the Apollo 11 flag reportedly fell down when the astronauts blasted off from the lunar surface), but decades of UV radiation from unfiltered sunlight have likely bleached the remaining flags white. For example, the Apollo 11 Stars and Stripes wasn’t some meticulously designed space flag capable of surviving the harsh lunar climate, but a $6 nylon flag that may have been purchased at a Sears Roebuck in the Houston area. Some have theorized that the nylon could’ve disintegrated completely, but NASA has examined flag sites using the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and has found evidence of the flags still “flying.” In November 1969, only a few months after Neil Armstrong took his famous “one small step” on the moon, U.S. Congress passed a law stipulating that a U.S. flag would adorn any moon, planet, or asteroid during missions fully funded by the Americans. In other words, an international effort to land on Mars, for example, means no U.S. flag will fly on the red planet (not that it’d last very long anyway).

The U.S. Flag Might Need a 51st Star Pretty Soon

The 50-star U.S. flag is the longest-serving banner in U.S. history, being the country’s official flag for more than 60 years (the 48-star flag comes in second, at 47 years). However, three primary candidates — Puerto Rico, Washington, D.C., and Guam — could one day necessitate a new U.S. flag with 51 (or more) stars. To solve this constellation conundrum for all future generations, the online magazine Slate asked a mathematician to develop a model for the U.S.’s 51-star flag, as well as other flags containing as many as 100 stars. Potentials for a 51-star flag include six alternating rows of nine and eight stars, or a variation on the 44-star Wyoming pattern (created to accommodate Wyoming’s admission to the union in 1890), which would use five rows of seven stars sandwiched between two rows of eight stars. (As a refresher, the current flag has five rows of six stars and four rows of five stars.)

This isn’t the only competing 51-star flag; the pro-statehood New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico designed a flag similar to the original Betsy Ross flag, but the circle is instead jam-packed with 51 stars. The most likely 51st state, Puerto Rico, continues its push for statehood, and it’s possible that the long reign of the 50-star flag could be nearing its end.

Darren Orf lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes about all things science and climate. You can find his previous work at Popular Mechanics, Inverse, Gizmodo, and Paste, among others.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.