6 Interesting Facts About Our Hair

Original photo by west/ iStock

Long, beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming

Streaming, flaxen, waxen

Give me down to there (hair)

Shoulder length or longer (hair)

No, these aren’t the words of a shampoo commercial. When American men were drafted to fight in Vietnam, their hair was cut short. Long locks on men became a sign of defiance, and such hairdos seemed thrillingly shocking to theatergoers, who flocked to the rock musical Hair (which featured the song above) when it opened on Broadway in 1968.

Hair has sent cultural messages for millennia. It also sends signals about our body chemistry, including our age and health (which may be the unconscious reason some of us get so upset about “bad hair” days). Let these six facts about hair show you a whole new side of your crowning glory.

Human Hair Contains Silicon and Gold

Although each person’s hair is a bit different, one strand usually contains 45% carbon, 28% oxygen, and 15% nitrogen. Hair also contains up to 12% to 15% water and traces of mineral elements, including copper, zinc, iron, and silicon. Our hair even contains gold, which is excreted from our bodies through both hair and skin. Babies have more gold in their hair than adults, because gold is passed along in breast milk. Overall, the average human body is said to contain around .2 milligrams (less than the weight of a poppy seed) of gold.

Some Hair Loss Is Normal

During your life, your hair grows, falls out, and regrows around 20 times. In fact, it’s normal to lose 100 hairs a day, and even more during the fall and spring. The reason may be that in areas with four seasons, the sun damages the hair bulbs during the summer, leading to hair loss in the fall. Winter cold restricts blood flow to the scalp, causing the spring shedding. The solution: Cover your head!

However, if you’re suddenly noticing much more hair in your brush or in your shower drain, you may be suffering from low iron, or anemia. This is more likely in people who menstruate if they have heavy periods. People also can experience temporary shedding after a sickness like COVID-19, with a change in estrogen levels after pregnancy or stopping birth control pills, or during menopause.

Hair Reveals Stress

It’s true: Stress can make hair go gray or white faster. But there’s good news, too. Gray or white strands can sometimes turn back to their previous color, according to a large international study in 2021. “Just like tree rings hold information about past decades, and rocks hold information about past centuries, hairs hold information about past months and years,” the researchers wrote.

These transformations can happen on hair anywhere on the body — sometimes quickly. One person in the study regained five hairs with color after they took a two-week holiday.

We Can Go White Overnight

Extreme stress can even turn hair white overnight (or at least very quickly). This may have happened to Queen of France Marie Antoinette before the morning she walked to the guillotine. Sir Thomas More’s hair is also said to have turned white overnight in the Tower of London before his execution. Dermatologists now call this rare phenomenon “Marie Antoinette syndrome.”

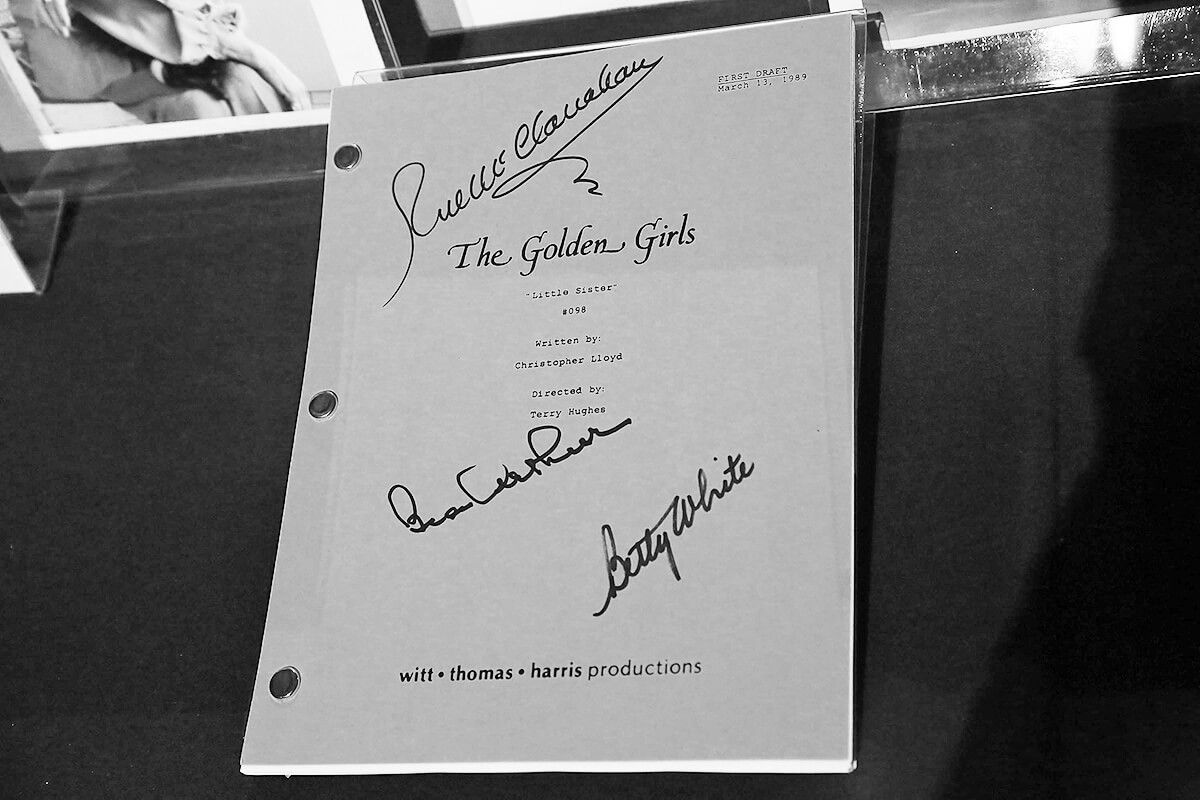

Wigs and Hair Dye Are Nothing New

Because hair reflects our mental and physical health, people have gone to great lengths throughout history to change its appearance. We dye away gray, use chemical products to fight hair loss, or wear wigs.

Dye to camouflage gray dates back at least to the ancient Egyptians, who used henna. The ancient Greeks used henna too (and even colored their horses’ tails with it).

In the Roman Empire, blond was a popular hair color. It had an exotic allure, and was associated with people from Gaul (modern France and Germany). Roman prostitutes were also required by law to have yellow hair to signal their status. Some very wealthy Romans even powdered their hair with gold dust. That was a more pleasant option than one dye that was used to turn hair black: fermented leeches.

The first commercial hair dye was created in 1907 by a French chemist, Eugene Schueller. He initially called his creation Aureole, but later renamed it L’Oréal, which was also the name of the company he founded two years later.

People Save Their Cut Hair

Among the sentimental Victorians, it was common to give locks of your hair to friends, family members, or lovers. The New York Public Library’s archives contain, for example, an auburn lock from Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein; a lock from Walt Whitman, author of Leaves of Grass; and a lock from Charlotte Bronte, who wrote Jane Eyre.

To this day, we continue to value hair as a memento. In 2009, a bidder paid $15,000 for a lock of Elvis Presley’s hair at an auction. That’s actually cheap: In 2021, a jar of the rock icon’s hair sold for $72,500.

Temma Ehrenfeld has written for a range of publications, from the Wall Street Journal and New York Times to science and literary magazines.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.