6 Monumental Facts About Mount Rushmore

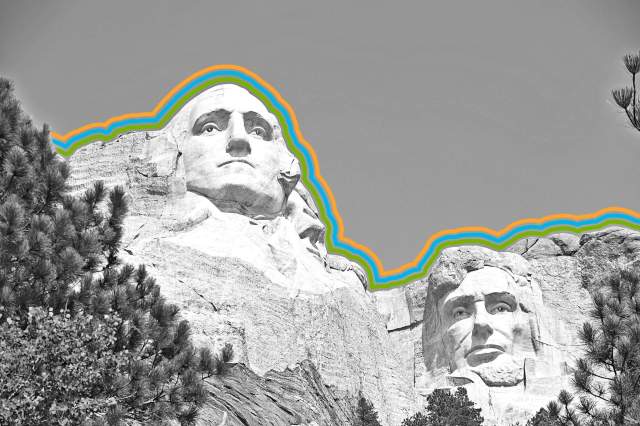

Original photo by e'walker/ Shutterstock

More than 2 million people visit Mount Rushmore each year, making the towering presidential monument South Dakota’s biggest tourist attraction. The sculptor behind the visionary memorial, Gutzon Borglum, called it “a shrine to democracy,” with the carved granite faces of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln symbolizing the founding of the nation and its timeless values. From its controversial location to its starring role in a classic Hitchcock caper, here are six fascinating facts you might not know about Mount Rushmore.

Mount Rushmore Has Been Controversial From the Start

The idea for a monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota generated controversy even before the first blast of dynamite took place. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed by the U.S. government and Sioux nations, reserved the Black Hills for the exclusive use of the Sioux peoples. The mountain that became Mount Rushmore is a sacred site in Lakota culture (part of the Sioux); its name translates to “the Six Grandfathers,” representing the supernatural deities that the Lakota believe are responsible for their creation. But within a decade, the U.S. had broken the treaty, leading to skirmishes including the U.S. defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. The federal government used its loss in the battle to justify its occupation of the Black Hills (which was later found to be unconstitutional).

Despite this bloody history, South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson proposed the Black Hills as the site for a new tourist attraction. He contacted sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who had recently been working on a monument to Confederate leaders on Stone Mountain in Georgia, and invited him to South Dakota. In 1925, Borglum began designing the colossal monument at Mount Rushmore (renamed for New York lawyer Charles E. Rushmore, who traveled to the Black Hills to review legal titles of properties in 1884). Once the project was approved and funded by Congress, carving commenced in October 1927.

Each Head on Mount Rushmore Is Over Five Stories Tall

With such a large canvas, chipping away with chisels was not going to cut it. Borglum used dynamite to blast away 90% of the granite rock face, which left between 3 and 6 inches of granite to be carved more finely. Workers suspended in slings from the top of the monument drilled a series of closely spaced holes to weaken the rock, then removed the excess chunks by hand. The detailed facial features were achieved with hand tools that left perfectly smooth surfaces.

In all, nearly 400 men and women spent over 14 years working on the monument. When the entire sculpture was completed in 1941, each presidential head measured about 60 feet tall. The Presidents’ eyes are roughly 11 feet wide, their noses measure about 21 feet long, and their mouths are around 18 feet wide. And because Mount Rushmore’s granite erodes extremely slowly — about 1 inch in 10,000 years — those features won’t shrink any time soon.

The Four Presidents Represent Specific Aspects of American History

The four Presidents depicted on Mount Rushmore were chosen for their key roles in American history. The carved face of George Washington, completed in 1930, is the most prominent figure on the memorial and represents the founding of the nation. Thomas Jefferson, dedicated in 1936, stands for the growth of the United States, thanks to his authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his roles in the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark expedition. Borglum chose the figure of Abraham Lincoln, dedicated in 1937, to represent American unity for his efforts to preserve the nation during the Civil War. Theodore Roosevelt, finished in 1939, symbolizes the development of the United States as a world power (he helped negotiate the construction of the Panama Canal, among other achievements) and champion of the worker as he fought to end corporate monopolies.

Some Have Proposed Additions to Mount Rushmore

Various additions to Mount Rushmore’s pantheon have been suggested over the decades. In 1937, a woman named Rose Arnold Powell enlisted the help of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in her proposal to add the head of Susan B. Anthony, but Congress ultimately refused to allocate funds. Other suggestions have included the additions of Presidents John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and even Barack Obama. However, the mountain’s original sculptor Gutzon Borglum insisted that the rock was unable to support further carving, and modern engineers have backed up that claim.

There’s a Semi-Secret Vault Behind the Sculpture

Borglum’s initial plans for Mount Rushmore called for a grand Hall of Records within the mountain behind Lincoln’s head. The 100-foot-long hall was planned to house the Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution, and other documents key to the nation’s history. Borglum envisioned the hall to be decorated with busts of notable Americans and a gigantic gold-plated eagle with a 38-foot wingspan over the entrance. But the twin tragedies of Borglum’s death in 1941 and the start of World War II put an end to his vision. The half-excavated chamber sat empty until 1998, when officials placed 16 panels explaining the history of the monument and its sculptor — along with the words to the Bill of Rights, U.S. Constitution, and Declaration of Independence — in a box and sealed it inside the vault. The chamber remains closed to the public.

The National Park Service Didn’t Want Hitchcock to Film “North by Northwest” at Mount Rushmore

The climax of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 thriller North by Northwest has Roger Thornhill (played by Cary Grant) and Eve Kendall (played by Eva Marie Saint) dangling over the precipice of Mount Rushmore as a villain tries to push them off. However, prior to filming, the National Park Service worried that the filmmakers would desecrate the monument. The agency made Hitchcock agree to strict rules, including promising not to shoot any violent scenes at Mount Rushmore or have live actors scrambling over the Presidents’ faces, even on a soundstage mock-up.

But the director failed to keep his word. Days before the film’s premiere, the park service issued a terse statement calling the movie “a crass violation of its permit” and wanting to “make the record clear on what the agreement provided and who failed to live up to it.” Still, the editor of the local Sioux Falls newspaper recognized the movie’s legacy. “Obviously,” he wrote, “this picture is worth its weight in gold to Rushmore from a publicity viewpoint.”

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.