8 Dazzling Facts About the Sun

Original photo by Lia Koltyrina/ Shutterstock

While there’s a lot happening on Earth, the sun is the real star of our show — pun intended. Hanging out at an average 93 million miles away from Earth, the sun is a perfect mixture of hydrogen and helium that spit-roasts our planet just right as we travel around its bright, glowing body. But although the sun is central to our survival, there’s still a lot we don’t know about it. For decades, space agencies have been sending missions to explore the sun and find answers; in 2021, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe became the first spacecraft to “touch” the sun by entering its upper atmosphere (still some 4 million miles away from its surface). Based on research from these missions and more, here are some of the most interesting things we’ve learned about the sun — and some of our best guesses at what its future might look like.

The Sun Is Middle-Aged

The sun seems eternal — an ever-present, life-giving fireball in the sky — but not even it can escape the wear and tear of time. Some 4.6 billion years ago, the sun formed from a solar nebula, a spinning cloud of gas and dust that collapsed under its own gravity. During its stellar birth, nearly all of the nebula’s mass became the sun, leaving the rest to form the planets, moons, and other objects in our solar system. Even today, the sun makes up 99.8% of all mass in the solar system.

Currently in its yellow dwarf stage, the sun has about another 5 billion years to go before it uses up all its hydrogen, expands into a red giant, and eventually collapses into a white dwarf. So at 4.6 billion years old, the sun could be best described as “middle-aged” — but we don’t think it looks a day over 3 billion.

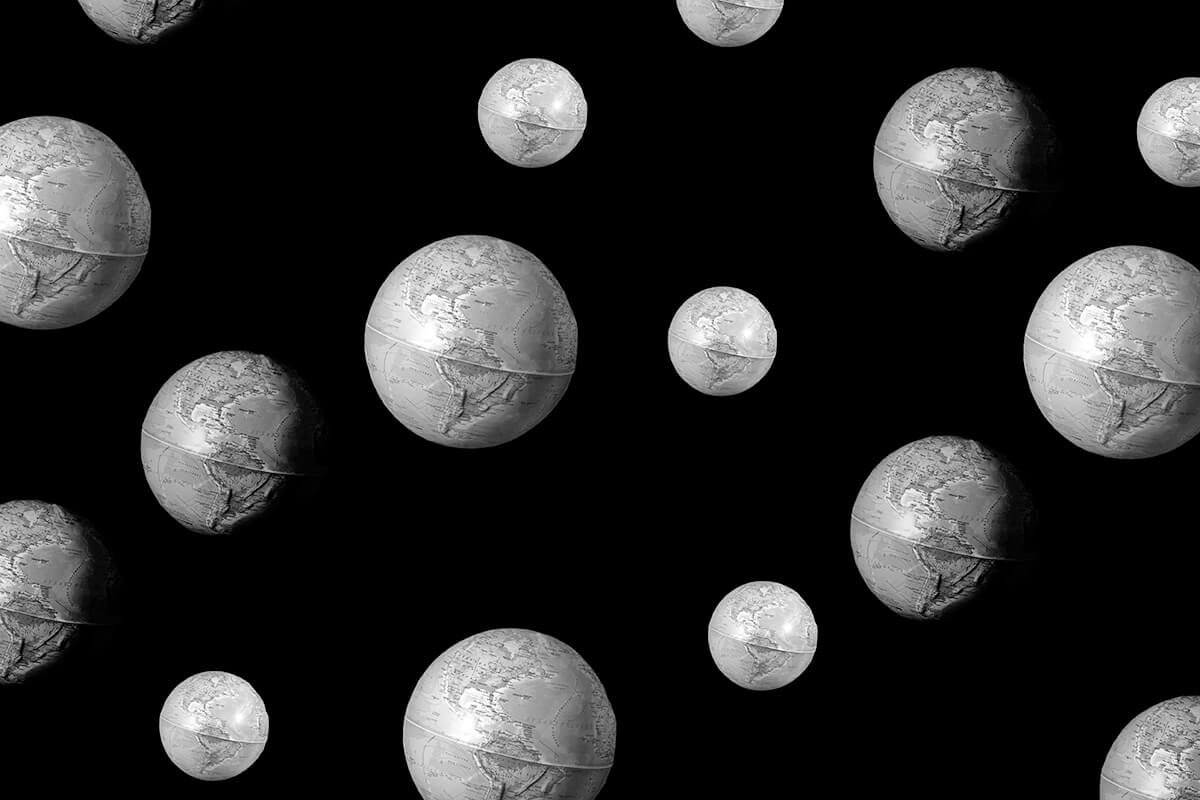

1.3 Million Earths Could Fit Inside the Sun

The Earth is big, but the sun is bigger — way bigger. Measuring 338,102,469,632,763,000 cubic miles in volume, the sun is by far the largest thing in our solar system, and some 1.3 million Earths could fit within it. Even if you placed Earth in the sun and maintained its spherical shape (instead of squishing it together to fit), the sun could still hold 960,000 Earths. Yet when it comes to stars, our sun is far from the biggest. For instance, Betelgeuse, a red giant some 642.5 light-years away, measures nearly 700 times larger and 14,000 times brighter than our sun.

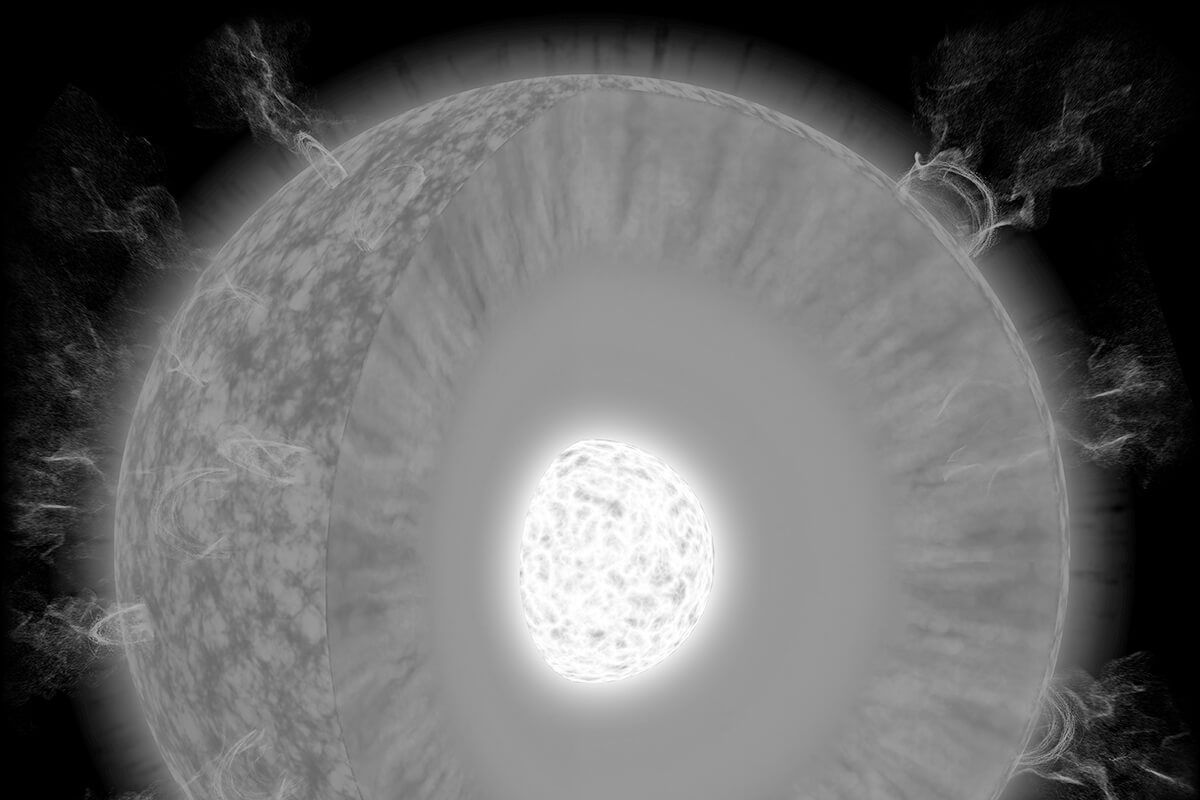

It Takes a Long Time for Light to Escape the Sun

The sunlight that reaches your eyes is older than you might think. It takes a little over eight minutes for photons from the surface of the sun to reach Earth, meaning every time you glimpse the sun (hopefully with sunglasses!), it actually looks as it appeared eight minutes ago. However, this photon blazing at the speed of light is at the end of a very long journey. Once a photon enters the sun’s “radiative zone,” the area between the core and the convective zone (the final layer which stretches to the surface), energy is absorbed after a very short distance into another atom, which then shoots that energy into yet another direction. The overall effect is what scientists call a “random walk,” and the result is that it can take a single photon thousands of years — up to 100,000 years — to escape the sun. As our knowledge of the sun grows, scientists will likely refine this number, but for now it’s safe to say that it takes “a long time.”

The Sun’s Atmosphere Is Much Hotter Than Its Surface

As you travel farther from the surface of Earth, things usually get colder and colder. Planes traveling at 35,000 feet, for example, travel through the stratosphere and experience temperatures around -60 degrees Fahrenheit. However, the sun’s atmosphere works in exactly the opposite way. While the surface of the sun hovers around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, the atmosphere (or corona) of the sun is hundreds of times hotter, with temperatures reaching up to 3.6 million degrees Fahrenheit.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure why the sun’s atmosphere is so much hotter than the surface. One leading theory is that a series of explosions called “nanoflares” release heat upwards of 18 million degrees Fahrenheit throughout the atmosphere. Although small when compared to the sun, these nanoflares are the equivalent of a 10 megaton hydrogen bomb, and approximately a million of them “go off” across the sun every second. Another theory is that the sun’s magnetic field is somehow transferring heat from its core, which rests at a blazing 27 million degrees Fahrenheit, to its corona.

Different Parts of the Sun Rotate at Different Speeds

The sun doesn’t rotate like your typical planet. While the Earth’s core does rotate ever so slightly faster than the planet’s surface, it mostly moves as one solid mass. The sun? Not so much. First of all, it’s a giant ball of gas rather than a rigid sphere like Earth. The gases at the sun’s core spin about four times faster than at its surface. The sun’s gases also spin at different speeds depending on their latitude. For example, the gases at the sun’s equator rotate much faster than the areas at higher latitudes, closer to the poles. A rotation that takes 25 Earth days at the sun’s equator takes 35 days to make the same journey near the poles.

The Sun Completes Its Own Galactic Orbit Every 250 Million Years

Picture a grade-school model of the solar system, and it’s easy to forget that the sun is on its own galactic journey. While the Earth orbits the sun, the sun is orbiting the center of the Milky Way galaxy. On its orbiting journey, it travels roughly 140 miles per second, or about 450,000 miles per hour (by comparison, the Earth travels around the sun at only 67,000 miles per hour). Although blazing fast by Earth standards, it still takes our star roughly 230 million years to complete a full revolution.

In About 1 Billion Years, the Sun Will Kill All Life on Earth …

In 5 billion years, the sun will enter its red giant phase and engulf many of the inner solar system planets, including Earth. However, Earth will lose its ability to sustain life much earlier than that, because the sun is steadily getting hotter as it ages. Scientists estimate that anywhere between 600 million and 1.5 billion years from now, the Earth will experience a runaway greenhouse effect induced by our warming sun that will evaporate all water on Earth and make life on our blue marble impossible (except for maybe some tiny microorganisms buried deep underground). Eventually, Earth will resemble Venus, a hellish planet warmed beyond habitability due to its thick atmosphere and proximity to the sun. Luckily, humanity has at least several hundred million years to figure out a plan B.

… But Life Only Exists Because of the Sun in the First Place

You can’t get too mad at the sun for its warming ways, because life couldn’t exist without it. Earth is perfectly placed in what astronomers call a star’s “goldilocks zone,” where the sun isn’t too hot or too cold but just right. This advantageous distance has allowed life to flourish on Earth, with the sun bathing our planet in life-giving warmth. The sun also gives plants the light they need to grow and produce oxygen, which in turn forms the bedrock of the web of life — and it’s all thanks to the middle-aged, hydrogen-burning, massively huge star at the center of our solar system.

Interesting Facts writers have been seen in Popular Mechanics, Mental Floss, A+E Networks, and more. They’re fascinated by history, science, food, culture, and the world around them.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.