7 Sweet Facts About the Color Pink

Original photo by TatianaMironenko/ iStock

Pink is arguably one of the most popular tints in existence, and its warm tone is full of meaning both historical and cultural. Its importance shows up in the clothes we wear, the rooms we paint, and in some cultures, the accessories we use for our babies (though which ones depends on the time and place). These seven facts about the color pink may have you rethinking your relationship with this hugely popular hue.

Pink Is Named After a Type of Flower

Although the word “pink” is most often associated with the light-hued tint of the color red, the word actually originated with a specific genus of flower: Dianthus. While flowers in this genus (there are more than 300 species) are often pink, the term for the flower may have originally referred to the perforated or frayed edges of the blossoms — at the time, the verb “to pink” meant to decorate with a perforated pattern. (Think “pinking shears.”) Over time, the meaning shifted from the pattern to the color.

This isn’t the only “chicken before the egg” moment on the color wheel — “orange” was originally a reference to the fruit, and then became entwined with the color itself.

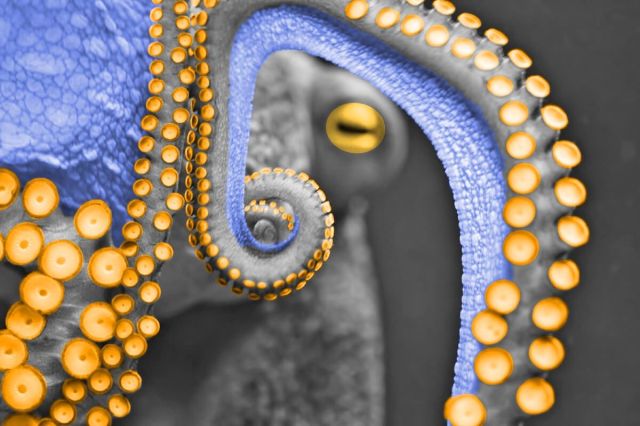

There Are Many Pink Lakes Around the World

According to at least one estimate, 117 million lakes exist on Earth, covering roughly 4% of its surface. Among these millions of lakes, most sport the bluish and brown hues commonly associated with landlocked bodies of water. However, there are a few lakes that stand out from the crowd, including more than two dozen or so pink lakes spread across the world.

Although pink lakes can be found on every continent except Antarctica, Australia has the lion’s share. One of its most pristine examples is Lake Hillier on Middle Island. While many lakes may be pink only a few months out of the year (during the warm, dry season), Lake Hillier has been permanently pink for centuries. This hue is caused by a salt-loving algae called Dunaliella salina, as well as a bacteria named Salinibacter ruber, which both produce pinkish pigments. Although it looks like a tasty bubblegum soda, it’s best not to take a sip — the lake is 10 times saltier than the ocean.

Pink Is an Nonspectral Color

There have been some heated debates online about whether pink is a true color. The argument may seem strange at first, but technically the color pink doesn’t exist without a little help from our eyes. That’s because pink is a nonspectral color, meaning it isn’t represented by a specific wavelength of light in the electromagnetic spectrum. In other words, in order to get pink, you need to combine spectral colors — in this case, red and white — which makes pink a construction of our minds.

Yet many colors we know and love are similarly nonspectral. Purple is a big one: It’s close to indigo and violet but technically isn’t found in that 380 to 740 nanometer sweet spot. Brown is similarly a nonspectral color. So cut pink some slack: While it may not technically exist, it’s certainly easy on the eyes.

Pink Was Once Considered a Masculine Color

These days, a baby’s biological sex is often denoted using blue for a boy and pink for a girl. However, this is a relatively recent development. Back in the 18th century, boys wore blue and pink in equal measure, and as late as 1918, an article in the trade journal Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department described pink as a “stronger color [that] is more suitable for the boy.” By the 1940s, the U.S. marketing machine established the current color/gender rules, and remnants of this idea are still with us today. However, younger men are more comfortable with wearing pink, so it’s likely this arbitrary distinction will likely fade away, and color styles will return to their 18th-century roots.

Some People Listen to Pink Noise To Fall Asleep

Similar to the electromagnetic spectrum and light, there is also a spectrum for sound that’s described using color. Most of us are familiar with “white noise,” which contains all the frequencies humans can hear in equal parts. (Its name comes from the visible light spectrum: Just as white light is made up of all the colors, white noise combines all the frequencies of sound.) Pink noise contains all sounds in this same spectrum, but emphasizes lower frequencies. Some things naturally create white noise, including waves crashing on the beach or rain falling, which are often soundscapes people turn to when in need of a good night’s sleep. But if that white noise machine maybe sounds a bit too grating, give pink noise a shot.

One of India’s State Capitals Is Named “The Pink City”

Originally founded in 1727, Jaipur is now the capital of the state of Rajasthan in northwestern India. While Jaipur is the region’s largest city, it’s also known for another startling characteristic — many of its buildings are painted in rosy hues. To understand this unexpected architectural choice requires a look back in history. In 1876, Maharaja Ram Singh, who ruled Jaipur from 1835 to 1880, painted the city’s buildings pink in preparation for a visit from Prince Albert Edward, Queen Victoria’s eldest son. The maharaja chose this specific hue because pink is traditionally associated with welcome and hospitality throughout India. Fast-forward nearly 150 years, and Jaipur is now one of the most Instagrammable cities in the world.

Scientists Discovered a Pink Exoplanet in 2013

Our solar system is filled with eye-popping color. Of course, there’s the “pale blue dot” known as Earth, but there’s also our next-door neighbor the red planet, as well as the calming, icy blues of Neptune, the tempestuous browns of Jupiter, and the butterscotch otherworldliness of Saturn. Our cosmic neighborhood doesn’t sport any pink planets — but the same cannot be said for the rest of our galaxy.

In 2013, NASA spotted a peculiar gas giant circling the star GJ 504 (faintly visible by the unaided eye in the constellation Virgo) some 57 light-years from Earth. This gas giant, simply called GJ 504b, is about the size of Jupiter — and it’s bright pink. NASA describes the color as a “dark cherry blossom,” and the shade is due to the planet “still glowing from the heat of its formation.” So while seeing this pink world would be quite the sight, best to scratch it off your bucket list unless your idea of a tropical getaway includes 460-degree Fahrenheit temperatures.

Darren Orf lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes about all things science and climate. You can find his previous work at Popular Mechanics, Inverse, Gizmodo, and Paste, among others.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.