6 Fascinating Facts About May Day

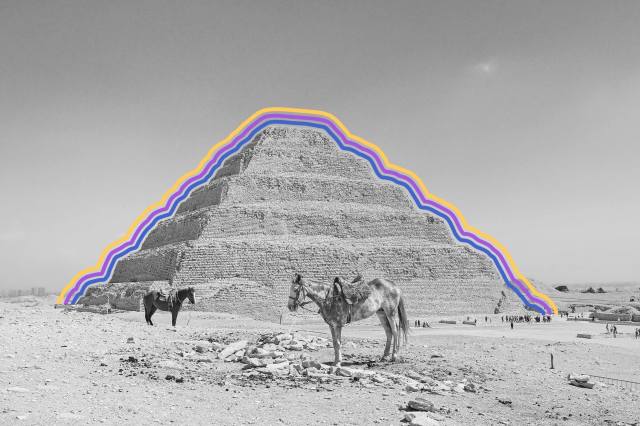

Original photo by Laura Stone/ Shutterstock

May Day has been a day of celebration in Europe for centuries, if not longer. The festival most likely arose out of ancient rites asking gods for fertile crops and healthy livestock. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, laborers welcomed spring with a day of drinking and dancing. Today, May Day is a public holiday in more than 180 countries around the world. These facts cover both its ancient origins and more modern symbolism honoring workers.

The Scots Believed May Day Dew Had Mystical Powers

The Druids, the religious leaders of the ancient Celts, made fires on the hilltops to honor the sun at dawn on May 1 in a festival called Beltane. They sprinkled themselves with May Day dew, considered a kind of holy water that would bring health and good fortune.

Scots, mainly young women, kept part of this tradition alive, ascending the nearest hill around 4 a.m. on May 1 to wash their faces in May Day dew. The desired outcome? A lovely complexion. As late as 1968, some 2,000 people climbed up Arthur’s Seat, an ancient volcano in Edinburgh, for the rite: “The summit of the hill was crowded with people old and young, huddled together trying to keep warm in the crisp, clear morning air,” by one account. In more recent years, however, the numbers who brave the cold for the sake of beauty have dwindled.

Maypole Ribbon Dancing Began in Victorian Times

You may have seen modern-day versions of old May Day traditions, with a May Queen crowned and maypole dances. Nowadays, you’ll likely see dancers each holding a ribbon that is interwoven around the pole.

But May Day dancing didn’t always include ribbons. Medieval Celts stripped a tree and wrapped it in flowers on Beltane. In the ensuing British tradition, villagers danced around a tall tree or a pole, still decorated with flowers. The first known maypole dance featuring people holding ribbons appeared in an 1836 play at the Royal Victoria Theatre in London. Afterward, villages picked up the idea and created their own variations.

May Day Celebrations Were Controversial in the American Colonies

For the devout Pilgrims who came to the New World, debaucherous May Day celebrations were forbidden — which is a large part of why the holiday has never been celebrated in the U.S. as it is in Europe. Yet a small group of traders came over around the same time as the Puritans to make money, not to escape religious persecution. They settled near Plymouth in a camp called Merry Mount. For May Day 1628, they set up an 80-foot-tall pine maypole crowned with deer antlers. One man, Thomas Morton, brewed a barrel of beer and invited Indigenous young women to the celebration.

Scandalized, the colony’s Puritan governor, William Bradford, declared that Morton had “revived and celebrated the feasts of the Roman goddess Flora,” linked to “the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians.” He placed Morton in the stocks — a device restraining one’s legs or feet — and sent him home to England. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a short story about the event, declaring that “May, or her mirthful spirit, dwelt all the year round at Merry Mount.”

London Erupted in Riots on May Day

May Day hasn’t always been merry. In 1517, more than 1,000 angry Londoners rioted on what would be called “Evil May Day.” While the upper classes under King Henry VIII enjoyed luxuries like silks, spices, and oranges imported from abroad, poor Londoners felt that foreign workers were taking their work away. When city and royal officials charged nearly 300 Londoners with treason in the aftermath of the riots, the queen of Aragon begged her husband on her knees to show mercy. Nearly all of the people charged were pardoned.

May Day Commemorates the Haymarket Riot in Chicago

Nearly 400 years after “Evil May Day,” early May saw another worker protest that turned violent. It began with calls for a nationwide general strike (in support of an eight-hour workday), to occur on May 1, 1886. On May 3 in Chicago that year, police attacked and killed several picketing workers at a plant. At a protest meeting in Haymarket Square the following day, someone threw a bomb at the police, who opened fire; in the ensuing riot, seven police officers and four workers died. By August, eight men had been convicted for their supposed role in the bombing. Yet many considered them martyrs to the worker cause.

To commemorate this occasion, in 1889 an international group of Socialist organizations and unions declared May 1 a day to support workers. The date became especially important in the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, with major parades. May Day is still celebrated as International Workers’ Day, although in the U.S. workers and laborers are more likely to be honored on Labor Day.

The Finns Do It Up

The Finns observe Vappu from April 30 to May 1. The holiday honors St. Walpurga, and is also a celebration of the working class and students. Adults pull out their old white hats from high school graduation, wear costumes, and drink champagne or nonalcoholic mead while eating doughnuts at picnics in the parks. In Helsinki, the fun begins at 6 p.m. on April 30, when students gather at the Market Square to wash and put a white cap on the head of an Art Nouveau statue of a mermaid.

Temma Ehrenfeld has written for a range of publications, from the Wall Street Journal and New York Times to science and literary magazines.

top picks from the optimism network

Interesting Facts is part of Optimism, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.