Do Colors Look the Same to Everyone?

From the orange glow of a sunrise to the calming tones we choose to paint our bedrooms, color shapes the way we experience the world. It influences our moods, choices, and memories, and it adds a layer of emotional depth to everything we see.

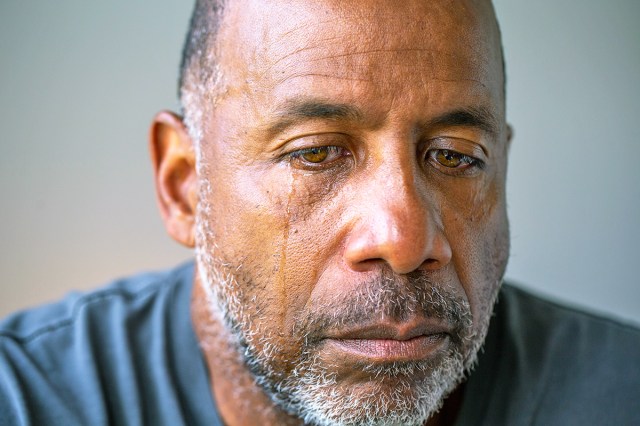

Yet you may be surprised to learn that colors, despite being such an important part of the human experience, aren’t universally perceived the same way. Two people may look at the same object and experience the color differently, depending on various factors such as how their eyes and brains process light. Those variations remind us that the colors we take for granted are filtered through biology and culture, making our experience of the world more unique than we might realize.

How We Perceive Color

Color perception begins in the eye, specifically with the retina’s photoreceptor cells called cones. Humans typically have three types — S-cones, M-cones, and L-cones — that detect short, medium, and long wavelengths, roughly corresponding to blue, green, and red light. Those cones send signals to the brain, where they are interpreted as the colors we see.

However, not everyone’s eyes perceive color the same way. Color vision deficiencies, often called color-blindness, affect millions around the world — roughly one in 12 men and one in 200 women — shaping how they experience color.

Red-green color-blindness makes it hard to pick out reds and greens, sometimes muting them or making them indistinguishable from each other. Less common forms include blue-yellow deficiencies, which blur blues, greens, yellows, and reds, and monochromacy (achromatopsia), which eliminates color entirely, causing people to see the world in shades of black, white, and gray.

Even subtle differences in cone distribution can alter perception. Two people gazing at the same sunset could describe it differently — one emphasizing the reds and oranges, the other noticing more purples and pinks.

Aging also plays a role: As the eye’s lens yellows over time, it begins to filter out blue light, lending colors a warmer, more muted tone. After cataract surgery, patients often report the world looking brighter or more vivid, a reminder of how physical changes in the eye affect what we perceive.

Color Perception Is Subjective and Changeable

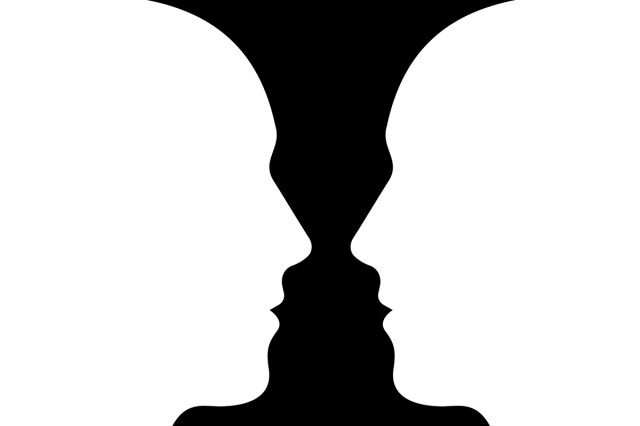

Our brains’ interpretations of color aren’t fixed — they’re dynamic and easily influenced by context. One reason for this is a phenomenon called color constancy, which is the brain’s ability to recognize the same color under different lighting conditions.

For example, a white shirt appears white in both sunlight and indoor lighting, even though the wavelengths reaching the eyes are very different. The brain adjusts for the light source, maintaining a consistent sense of color rather than shifting in hue.

Optical illusions, however, reveal the limits of color constancy. The viral internet phenomenon known as “the dress” — wherein some people saw a photo of a blue and black dress while others saw white and gold — shows how assumptions about lighting and shadow can completely alter our perception of color.

In that case, viewers unconsciously “corrected” for what they thought the light source was, leading to dramatically different interpretations of the same image. This is the same principle filmmakers relied on in The Wizard of Oz. The sudden burst of saturated color found in the Land of Oz feels especially vivid because our brains contrast it against the monochrome tones of the Kansas scenes.

Our everyday perceptions are just as personal. When choosing fruit at the grocery store, we use subtle color cues — such as the shift in hue from green to yellow in a banana or the deepening red of a ripe strawberry — to judge freshness. Some people focus more on saturation (how intense a color appears) rather than brightness (how light or dark the color seems), but both are part of how the brain interprets color in context.

Even our physical and emotional states can change how we see color. Fatigue can dull our sensitivity to contrast, certain medications can change how light is processed by the retina, and mood has even been shown to influence perception: People with a positive mindset often perceive colors as slightly more vivid.

Our Understanding of Color Perception Is Limited

Even with advances in science, one puzzle remains: our inner experiences of color. The “inverted spectrum” thought experiment, which dates back to at least the 17th century and philosophers including John Locke, imagines a scenario in which one person’s red may appear to them as another person’s green, even though both call it “red.”

This is a philosophical concept rather than a scientific claim, meant to illustrate the limits of our knowledge about subjective experience. Because we can’t step into another person’s perception, we can never know for certain how their colors compare to ours — or if two people truly experience the same hue the same way, even if they both call it “red.”

We know color perception involves a number of physical and psychological factors, but research is still uncovering just how personal and varied it can be. Genetics and neuroscience show that differences in our eyes and brain pathways shape our perception of the colors we see. Brain imaging studies reveal how the visual cortex interprets color, and experiments with color-blind individuals show how adaptable our brains can be to different ways of seeing.

While we may never be able to fully view the world through someone else’s eyes, studying color perception can help us understand the fascinating mix of biology, culture, and consciousness that allows us to experience the world in our own unique ways.

Kristina is a coffee-fueled writer living happily ever after with her family in the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia.

top picks from the Inbox Studio network

Interesting Facts is part of Inbox Studio, which publishes content that uplifts, informs, and inspires.