Endicott Pear Tree

Early settlers in America hoped to put down long-lasting roots. Some, like Massachusetts Governor John Endecott, did so literally. After arriving in the colonies in 1628, Endecott was granted 300 acres outside Salem, where he built a homestead and planted pear trees in the 1630s, likely in order to produce perry, a cider-like alcoholic drink. Endecott hoped his orchard would continue to produce for generations to come.

That hope was at least partially satisfied. Some 131 years after his death, a local reverend noted in his diary that the governor’s plantings had dwindled save for one lone pear tree. In 1809, pears from that remaining tree were harvested and sent to former President John Adams. At the turn of the 20th century, newspaper reports highlighted the tree’s longevity, noting it still produced pears with “not of too pleasant flavor.” In the centuries since its planting, the pear tree has survived years of neglect, harsh New England weather, and vandalism to become the oldest living cultivated fruit tree in America. (The tree’s name is now usually spelled “Endicott,” the family’s modern spelling of their name.)

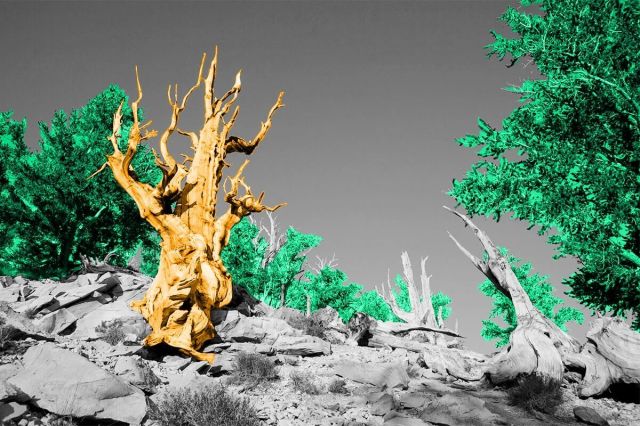

Methuselah

Methuselah, a bristlecone pine hidden within California’s Inyo National Forest, takes its name from the Bible’s longest-living figure, though it put down roots some 2,700 years before the birth of Jesus. Nestled within California’s White Mountains, the nearly 4,800-year-old tree lives within a grove of fellow bristlecones that may reach around 5,000 years of age. That long life span isn’t because of their location — the Inyo National Forest is known for being a hostile environment for plant life, combining high altitude with extreme temperatures that only the most persistent lifeforms can endure. Bristlecone pines grow slowly, an estimated inch per century, in effect making these resilient trees defenseless against vandalism and over-trafficking (one reason the U.S. Forest Service gives for not publicizing Methuselah’s exact location). The Guinness Book of World Records currently considers Methuselah the oldest living individual tree in the world.

Emancipation Oak

Trees provide oxygen, shade, and in some cases, a refuge from the world around us. The Emancipation Oak, shading the entrance of Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia, is one such tree; its limbs offered sanctuary to Black students during the height of the Civil War. Mary Smith Kelsey Peake, a free Black woman, began teaching formerly enslaved students at the base of the tree in 1861, a risk she undertook at a time when laws forbade the education of Black and enslaved people. The tree’s proximity to a Union Army base offered security — earlier in 1861, Union leaders had declared that enslaved people who reached Union lines would not be returned, bringing a wave of escapees to Fort Monroe, located in Confederate territory.

In 1863, an audience gathered beneath the tree’s branches to hear the Emancipation Proclamation — the first reading of the document in a southern U.S. state. Five years later, Mary Smith Kelsey Peake’s efforts would be recognized with the opening of what would later become Hampton University, near where she began teaching. The Emancipation Oak is now on the Virginia Landmarks Register, and in 2010, President Barack Obama recognized the tree’s significance by planting a sapling from the Emancipation Oak on White House grounds.

More Interesting Reads

Hyperion

Finding the world’s tallest tree is no easy feat, but one section of California keeps unearthing record-breaking trees that compete for the title. Countless timber titans are hidden deep within Humboldt Redwoods State Park and Redwood National Park along the state’s northwest coast. Researchers believe the area provides the perfect conditions for sky-high coast redwood trees: mild 40- to 60-degree temperatures paired with 60 inches of rain each year that allow for continuous growth. That’s likely how Hyperion, the world’s tallest tree, reached its stunning height of over 380 feet, far surpassing landmarks like the Statue of Liberty or Big Ben.

Discovered in 2006, Hyperion replaced the former reigning champ Stratosphere Giant, a fellow redwood that held the title for four years. But it’s unsurprising that any redwood tree receives the designation; many are able to reach staggering heights thanks to their generous 700-year life spans, with some surpassing 2,000 years old.

If you’re interested in hiking out to find Hyperion, know that it won’t be easy. Efforts have been made to keep the tree’s location secret in an effort to protect it from vandalism and foot traffic that could degrade its surrounding ecosystem.

Hibakujumoku

Ginkgo biloba trees are known for their ability to survive earthquakes, fires, and all manner of natural disasters. But no one could have guessed the slender trees with fan-shaped leaves would endure one of the darkest moments in modern human history: the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The devastation in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, left 5 square miles of destruction and an estimated 140,000 people dead. The initial blast, paired with high levels of radiation, killed off most trees and vegetation within the area. But by the following spring of 1946, Hiroshima residents realized that their singed, barkless ginkgo trees had once again bloomed, inspiring hope among survivors in the difficult days ahead. The surviving 170 trees, called hibakujumoku or “survivor trees,” are labeled with plaques that share their story and stand as reminders of resiliency, reconciliation, and peace — themes that transcend any season.