Farmer’s Almanacs

Long before scientific forecasting, people relied on folklore, observation of the skies, and seasonal almanacs to anticipate weather. The Old Farmer’s Almanac, first published in 1792, used a formula that was said to include solar activity, weather patterns, and astronomical cycles.

Farmers and households turned to it for long-range forecasts, sometimes with uncanny accuracy, but just as often with results no better than chance. Folk sayings such as “red sky at night, sailor’s delight. Red sky in morning, sailor’s warning,” based on observations passed down through generations, also acted as early weather guides.

While those early methods provided some rough counsel, they lacked the precision we expect today. Weather forecasting as a true science began in the mid-19th century, when telegraph systems allowed rapid sharing of weather observations across regions, enabling the first warnings of approaching storms. Still, predictions in those days were only reliable a few hours in advance.

Observation

Today, the first step in predicting weather is gathering data. Meteorologists monitor the atmosphere using a combination of ground-based instruments, weather balloons, satellites, and radar. Ground stations measure temperature, humidity, wind speed, and air pressure in specific locations. Weather balloons carry instruments called radiosondes high into the atmosphere, providing readings of conditions at various altitudes.

Each observation provides a piece of the larger puzzle. For example, a sudden drop in air pressure can indicate an approaching storm, while wind patterns help predict where weather systems will move next. Collecting this data continuously from hundreds of thousands of points on Earth allows meteorologists to track the ever-changing atmosphere with remarkable detail.

Modern Tools

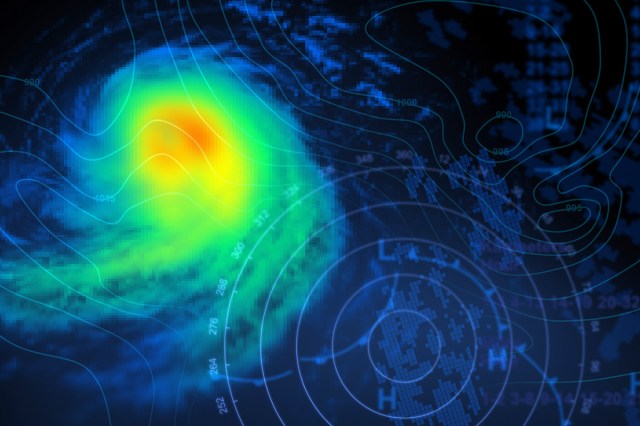

Satellites and radar are essential tools for modern meteorology. Weather satellites were first launched in the 1960s, giving meteorologists a powerful new tool for weather observation. As they orbit the Earth, satellites provide continuous images and measurements regarding factors such as cloud cover, temperature, humidity, and wind at different altitudes. Some can even measure rainfall and detect severe storms including hurricanes or typhoons before they reach populated areas.

Radar systems complement satellites by offering detailed, real-time information about precipitation. Doppler radar in particular can measure the speed and direction of rain droplets, allowing meteorologists to detect rotation in storms, which is a key factor in predicting tornadoes. By combining satellite imagery, radar data, and surface observations, forecasters can track storms as they develop and issue timely warnings to protect lives and property.

More Interesting Reads

Creating a Weather Model

Once data is collected, meteorologists turn to computer-based weather models to make sense of it. These models are mathematical simulations of the atmosphere that use physics and fluid dynamics to predict how weather systems will evolve. Essentially, the models take current conditions and calculate how they’re likely to change over time, producing forecasts that can range from a few hours to several days ahead.

There are many types of weather models, each with their own strengths. Some are global, simulating weather across the entire planet, while others are regional, focusing on a specific area for more precise predictions.

Small changes in the atmosphere can have large ripple effects on the weather, so forecasters often run multiple models and compare results to find the most likely outcome. This process, called ensemble forecasting, helps account for uncertainty and increases the reliability of predictions.

Turning Data Into Forecasts

After collecting data and running models, meteorologists interpret the results to create forecasts for the public. They consider model predictions, historical patterns, and the effects of local geographic features, such as mountains or large bodies of water, which can influence local weather. While computers run billions of calculations, it’s human expertise that ensures the final forecast adjusts for uncertainties and translates complex data into useful information.

Forecasts are usually presented as probabilities, such as a 70% chance of rain, to reflect the atmosphere’s unpredictability. Short-term forecasts can be highly accurate, sometimes down to the hour, while long-range forecasts beyond a week are less reliable.

Still, accuracy has improved dramatically over the past few decades due to our evolving technology: A seven-day forecast today being as accurate as a three-day forecast was in the 1980s. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), today’s five-day forecasts are accurate about 90% of the time, while seven-day forecasts are correct about 80% of the time.