Early Elves Were Mischief Makers

The concept of elves got its start in Northern Europe, from early Norse mythology to the Germanic folklore of the Middle Ages. Elf myths varied by region, and were often told in conjunction with fairy folklore. While some elves were benevolent, more often than not they were volatile troublemakers.

Illnesses, both human and animal, were often pinned on elves, as were bad dreams — supposedly, elves caused them by sitting on the sleeper. (The German word for nightmare, alpdrücken, translates literally to “elf pressure.”) They were even rumored to steal babies. While helpful elves sometimes worked their way into the mythology, early elves were certainly a far cry from the cheery toy manufacturers that came to dominate modern wintertime folklore.

Dancing Figured Prominently in Elf Mythology

In Scandinavian mythology, elves are typically portrayed as powerful, supernatural beings, and they often used music and dancing as a way to enchant and ensnare humans — like in the story of The Elf-Woman and Sir Olaf. In the tale, a knight stumbles into the elf world the day before his wedding and encounters elf maidens dancing. He’s asked to join the dance but refuses. As a result, he dies, although the ending differs in the story’s many variations. Another ballad, called “Elvehoj,” has a happier ending: Elf maidens attempt to draw him into dances that would permanently bind him to the elf world, but they’re ultimately unsuccessful.

Still another legend tells of the Elf-king’s tune: When a fiddler plays the song, it compels everyone in earshot, including inanimate objects, to dance. The fiddler can’t stop playing once the song has begun, unless he or she can play backwards, or someone cuts the fiddle’s strings. These dance themes continue in later Scandinavian texts, such as Hans Christian Andersen’s 1845 tale The Elf Mound, which describes elf maidens performing dances to impress party guests.

Christmas Elves First Emerged in the 19th Century

It wasn’t until the 1800s that elves began to be associated with Christmas. One of the earliest references was Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” (more commonly known as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas,” from its first line), which described Santa himself as a “jolly old elf.” In 1856, Little Women author Louisa May Alcott wrote a short story called “Christmas Elves” — but that story was never published, so it didn’t popularize the concept.

Nonetheless, the concept of Santa’s elves had certainly entered the cultural lexicon by the 1870s, when other works started mentioning elves. A December 1873 issue of Godey’s Lady Book — a highly influential women’s magazine that also helped popularize the Christmas tree as a tradition in America — led with an image of Santa’s workshop, complete with his elf helpers.

More Interesting Reads

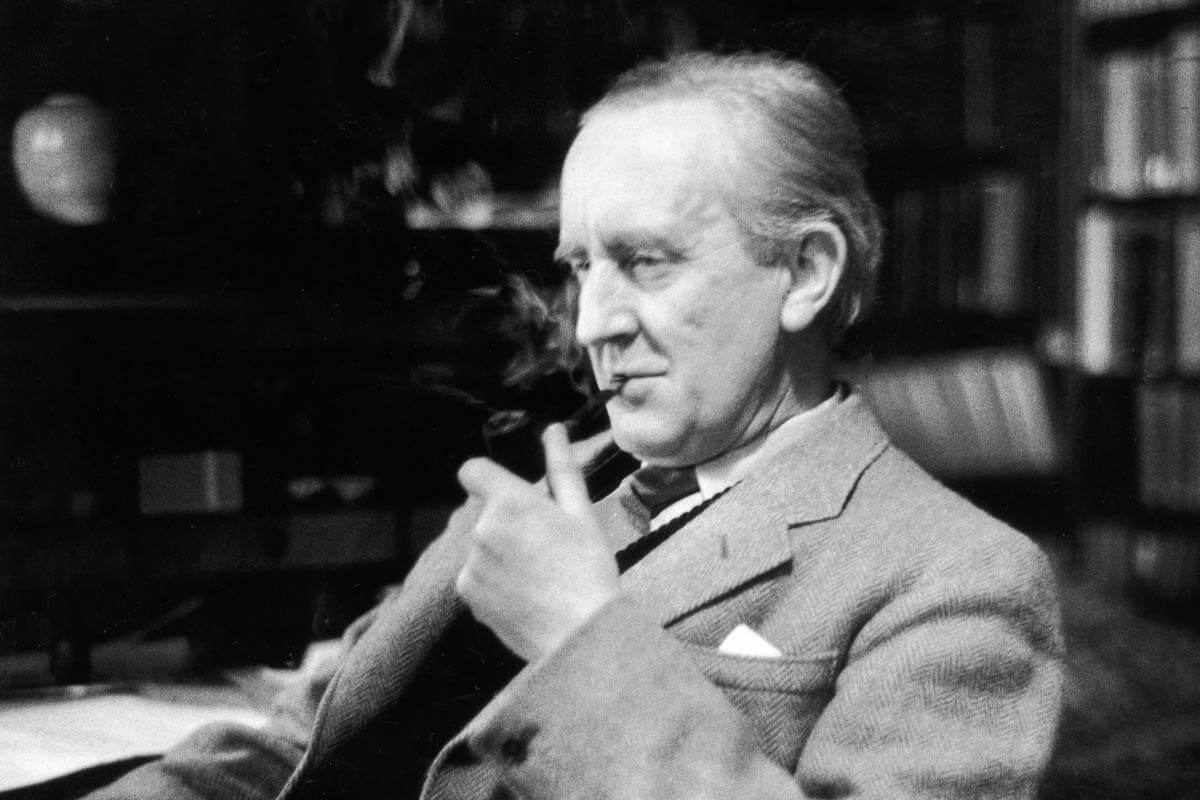

J.R.R. Tolkien Preferred the Middle English Word “Elven” Instead of “Elfin”

When J.R.R. Tolkien wrote his famous Lord of the Rings series, “elven” was considered an obsolete Middle English word. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), it was originally a noun that meant “female elf,” or simply “elf.” When Tolkien wrote the series, “elfish” or “elfin,” which had its first print appearance in 1590, were the terms used to describe “having to do with elves.”

Tolkien, also well known for his expertise in language and folklore, deliberately used “elven” and “elvish” instead, which became somewhat of a headache when it came time to proofread The Fellowship of the Ring. “The impertinent compositors have taken it upon themselves to correct, as they suppose, my spelling and grammar,” Tolkien wrote to his son in August 1953, “altering throughout ‘dwarves’ to ‘dwarfs’; ‘elvish’ to ‘elfish’… and worst of all, ‘elven’ — to ‘elfin.’”

To this day, neither Merriam-Webster nor Dictionary.com recognizes “elven” as a word, although Merriam-Webster recognizes “elvish.” The OED says that “elvish” specifically refers to elves as they’re described in Tolkien’s books, though the word has also become popular in other elf-related fantasy circles.

The Elf on a Shelf Tradition Started With a Self-Published Book

The Elf on a Shelf is a Christmas season ritual in which a parent hides a “Scout Elf” doll each morning for kids to find. The idea is that the elf watches the family, reports back to Santa at night if the kids have been naughty or nice, and then sets up in a different spot in the home for the next day.

This now-ubiquitous Christmas tradition dates to 2005, when a mother and her twin daughters pitched the idea for a book based on their own family ritual. After they were rejected by publishers, the trio took out credit cards and dipped into retirement funds to self-publish the book The Elf on the Shelf: A Christmas Tradition, which came with an elf for the reader’s own shelf. It was a runaway success, and over the next 15 years, more than 14.5 million Scout Elves were sold as the practice became a regular part of Christmas for families all over the world. The design of what’s now known as a “Scout Elf” is much older than the tradition itself. It bears a striking resemblance to the “knee-hugger” elves of the 1950s and 1960s; perhaps one of these was the family’s original elf.

One Elf in “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” Lacks a Notable Feature

There’s much that sets Hermy the Misfit Elf apart from the rest of his North Pole co-workers in the 1964 animated TV special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The most obvious and central to the plot is that he wants to be a dentist rather than manufacture toys. He also appears to be the only junior employee with a visible hairstyle — a stylish, swoopy blond mop.

But another feature sets Hermy apart that you may not have noticed: He does not have the pointy ears typically associated with elves. The other assembly workers, and even the gruff, goateed factory supervisor, all have pointy ears. Once you notice they are missing, it’s hard to unsee it, especially since his actual ears are quite small and rounded.